2. How Americans View the Humanities

While other surveys have inquired about certain aspects of humanities engagement, this survey is the first to thoroughly investigate public opinion about the field at a national level. The survey asked the public for their opinions about the field in three forms. First, after building up to a definition of the humanities by asking respondents about their engagement in humanities activities and then offering an explicit definition,9 the survey posed a series of questions about respondents’ level of agreement with statements about the field and its value (ranging from “the humanities should be an important part of every American’s education” to “the humanities are a waste of time”). Next, the survey asked respondents about their perceptions of a series of terms, including humanities; some of the field’s component disciplines (e.g., history, literature, philosophy); and other fields, such as science and engineering. A third category of perception questions—about the importance of teaching humanities subjects to young people—is addressed in Chapter 3.

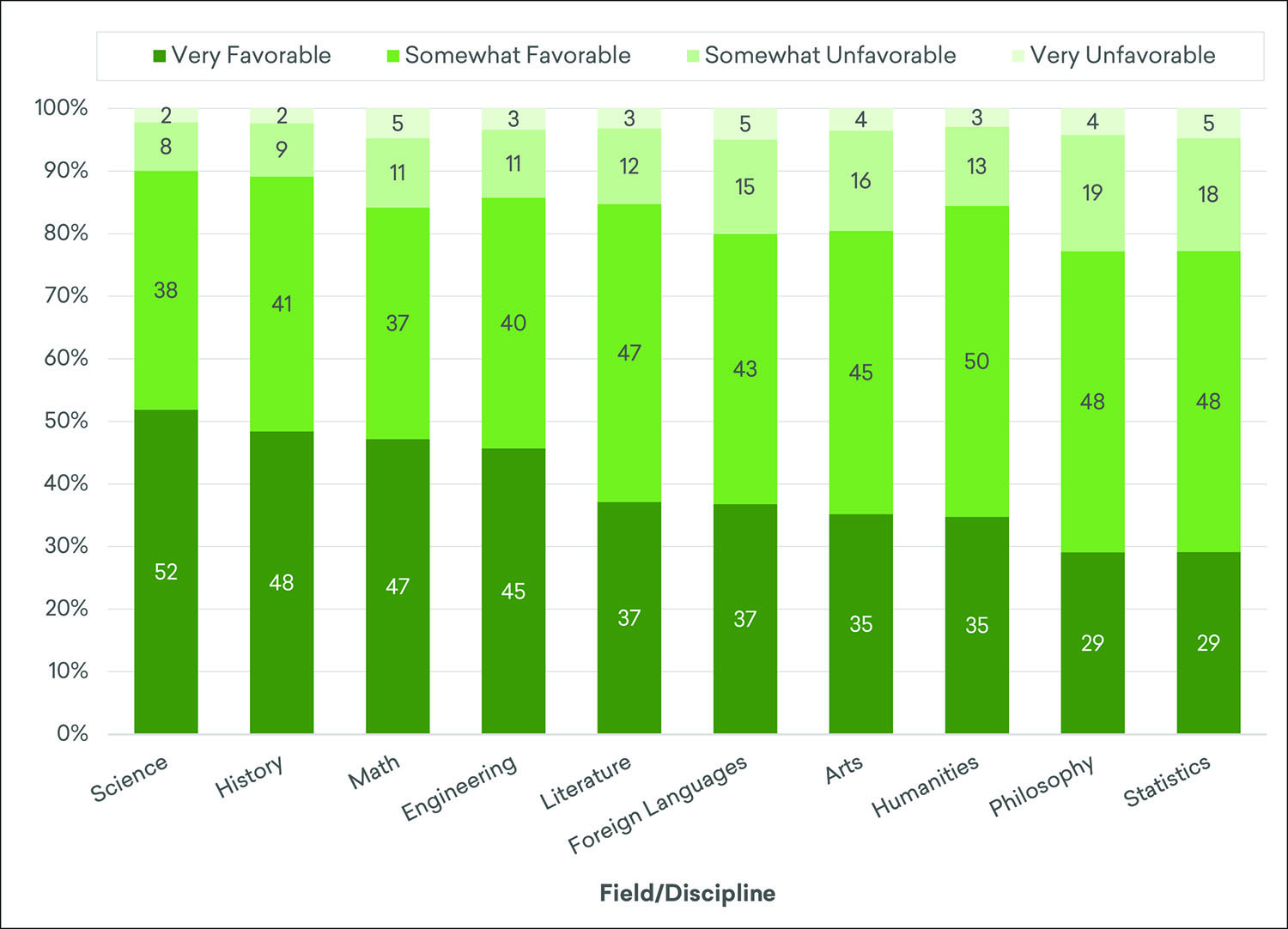

Favorability Ratings of the Humanities Compared to Other Fields

The humanities were similar to most science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields in the share of Americans having a favorable reaction to the terms, as 84–90% viewed each of these fields at least somewhat favorably (Figure 2A). Most of the STEM fields, however, were substantially more likely than the humanities to be viewed very favorably. While 35% of Americans responded very favorably to the term humanities, the term science was viewed very favorably by more than half of Americans, and engineering and math were viewed very favorably by approximately 46% of Americans.10

* Field/discipline bars are listed in descending order by the size of the share who had a very favorable impression of the term. The share values for a given field/discipline may sum to 99% or 101% due to rounding.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

In most cases, the public responded as favorably, if not more so, to particular humanities disciplines than to the broader field. Among the disciplines, history was particularly popular, with 48% of Americans viewing it very favorably, which was similar to the share for science (52%). The terms literature and foreign languages11 received ratings that were essentially the same as humanities, being viewed very favorably by 37% of Americans. Among the humanities disciplines, only in the case of philosophy did a smaller share react very favorably (29%), which put it on a par with statistics.

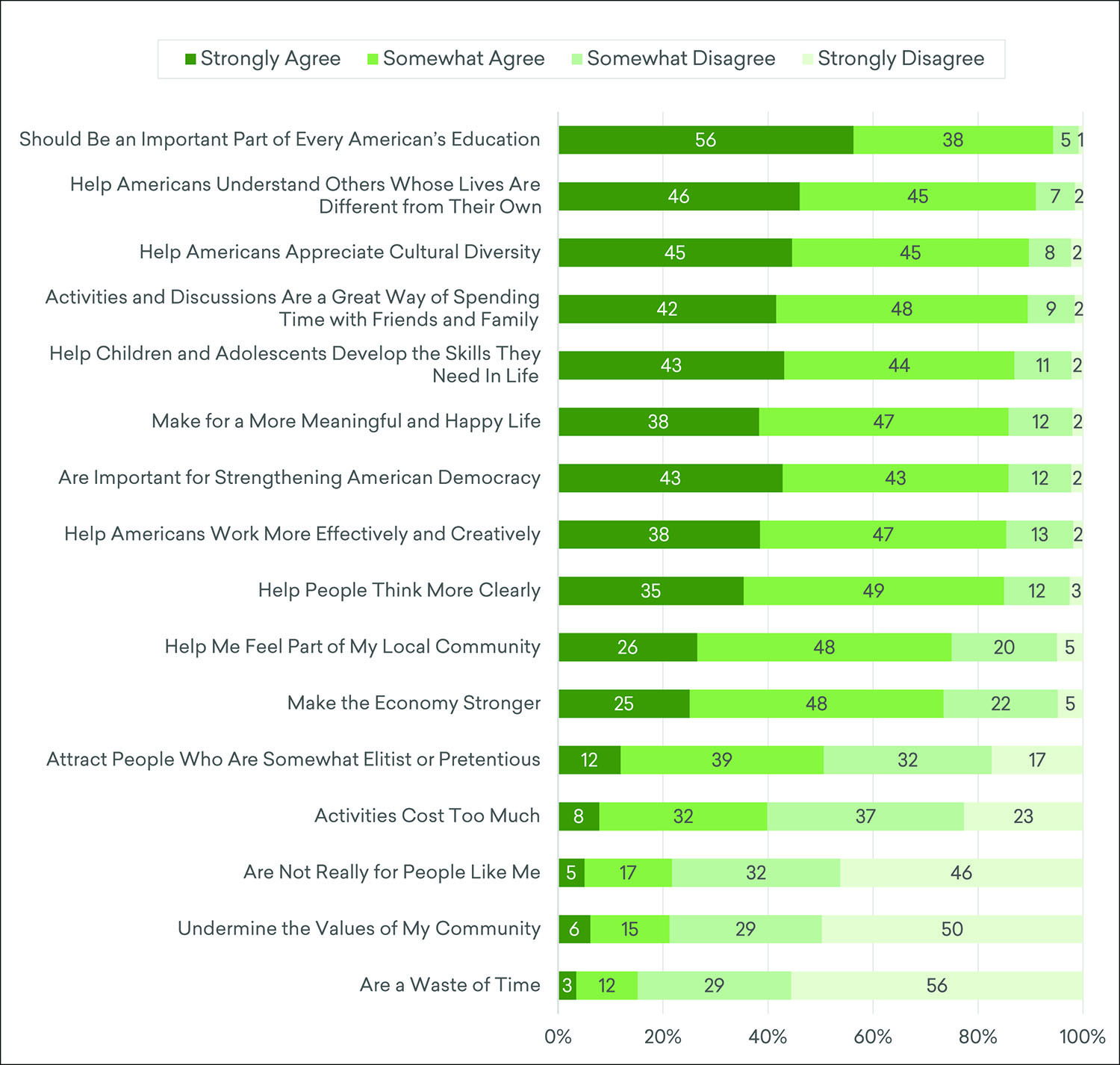

To probe more deeply into the public’s impressions about the value and utility of the field, the survey offered a series of positive and negative comments about the humanities (developed in consultation with stakeholders in the field) and asked respondents to indicate the strength of their agreement. More than 83% of Americans agreed at least somewhat with all but two of the positive comments, and (with one notable exception) at least 60% disagreed with each of the negative statements about the field (Figure 2B).

* Statements are listed in descending order by the size of the share who agreed at least somewhat. The share values for a given statement may sum to 99% or 101% due to rounding.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

The statement that received the greatest assent was “the humanities should be an important part of every American’s education”: 56% of Americans agreed strongly, and another 38% agreed somewhat. The positive statement to receive the lowest level of agreement was “the humanities make the economy stronger.” (Only 25% strongly agreed with this idea, though another 48% agreed somewhat.)

The negative propositions received the lowest levels of agreement in this portion of the survey, and a majority of Americans agreed with only one of them: that “the humanities attract people who are somewhat elitist or pretentious.” Only 12% of the adult population strongly agreed with this sentiment, but another 39% agreed somewhat. The only other negative statement to receive substantial agreement was the idea that “humanities activities cost too much.” Forty percent of Americans affirmed that view, though only 8% strongly agreed.

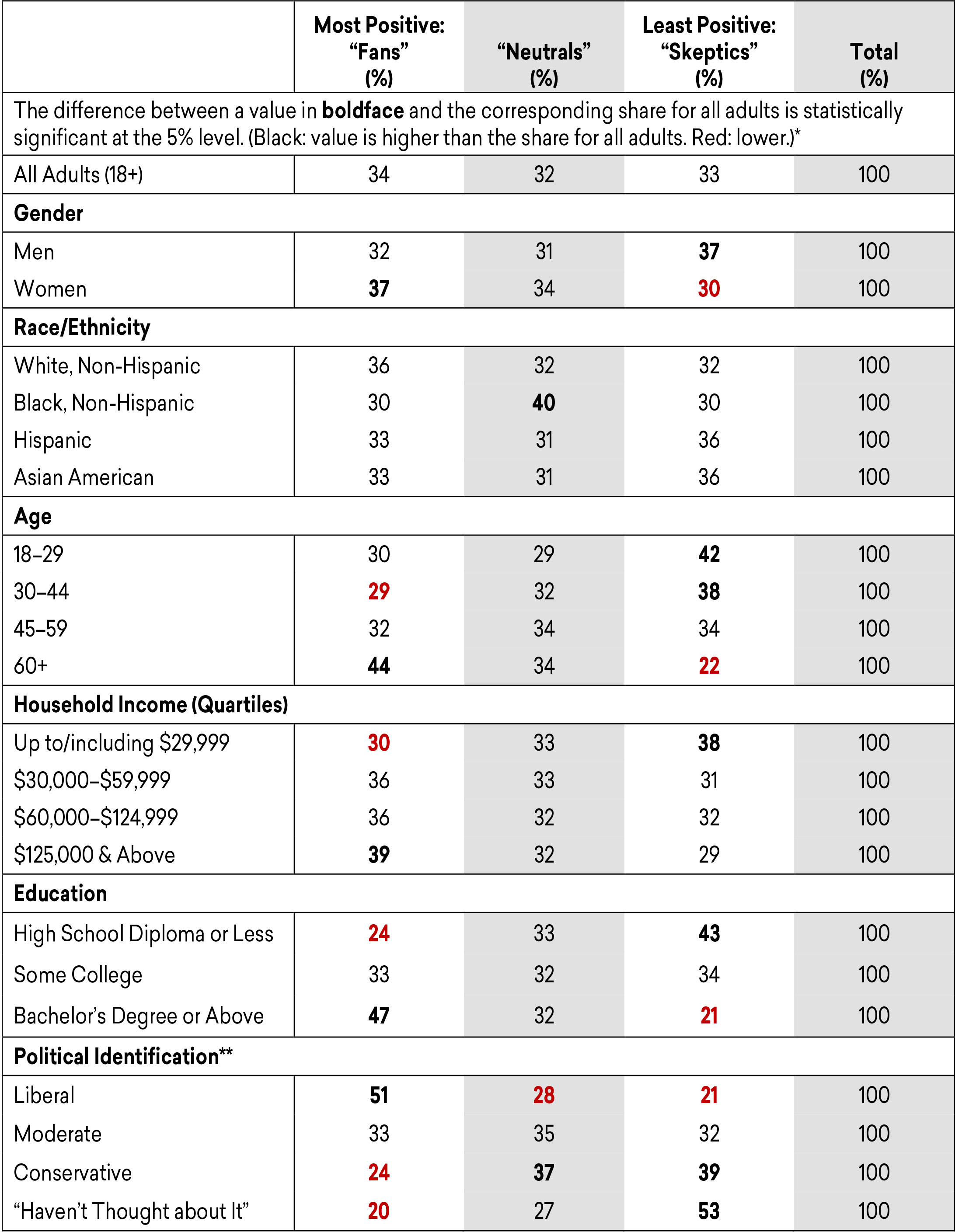

A scale comparable to that for engagement was constructed to gauge Americans’ overall perception of the humanities. (In the discussion below, the segment of the sample with the most positive view is referred to as “Fans”; the least enthusiastic are called “Skeptics.”)12 The study revealed substantial differences in Americans’ enthusiasm for the humanities—and some striking contrasts with engagement patterns (Figure 2C).

* Not every observed difference between demographic groups (e.g., between the youngest adults and those age 60+, or between Asian and White Americans) is statistically significant at the 5% level. The report narrative discusses notable differences that were found to be statistically significant. The “fans”/“neutrals”/“skeptics” shares for a given demographic group may sum to 99% or 101% due to rounding.

** Self-reported. Survey respondents were asked, “When it comes to politics, do you usually think of yourself as …?”. Liberal includes those who described themselves as “Liberal” or “Extremely Liberal;” Moderate includes those who identified as “Slightly Liberal,” “Moderate,” or “Slightly Conservative;” and Conservative includes those who identified as “Conservative” or “Extremely Conservative.”

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

While women were no likelier to have engaged with the humanities than men, they were somewhat likelier to be fans. And though older Americans were less likely than their younger counterparts to be among the most engaged, Americans age 60 and above were considerably more likely to be fans of the field than younger adults.

Conversely, Black Americans, while overrepresented among the most engaged, were not more likely to hold positive views of the field than other Americans. In fact, Blacks were somewhat less likely to be fans than Whites, and more likely to be neutral than both Whites and Hispanics. Substantial shares of Black Americans strongly agreed with many of the positive statements about the humanities, but they were also more likely than other racial/ethnic groups to agree with many of the negative statements.

While income was not related strongly or in a straightforward way with engagement, when it came to perception, there was a clear positive association, with the highest-income Americans more likely to be fans—and less likely to be skeptics—than the lowest-income Americans. This was attributable largely to more affluent Americans’ lack of agreement with negative statements about the humanities.

One area where engagement and perception did align was education. Americans with college degrees were not just more engaged with the humanities than those with less education (as discussed Chapter 1), they also expressed more enthusiasm for the field. Bachelor’s degree-holders were almost twice as likely as those without college experience to be fans.

The survey found an even sharper contrast by political identification, as 51% of liberals were fans, compared to just 24% of conservatives. The political segment that held the least favorable views about the humanities, however, was people who had not really thought about their political beliefs (described from here on out as “apolitical”). Over half of this group (which accounts for 12% of the adult population) were skeptics.

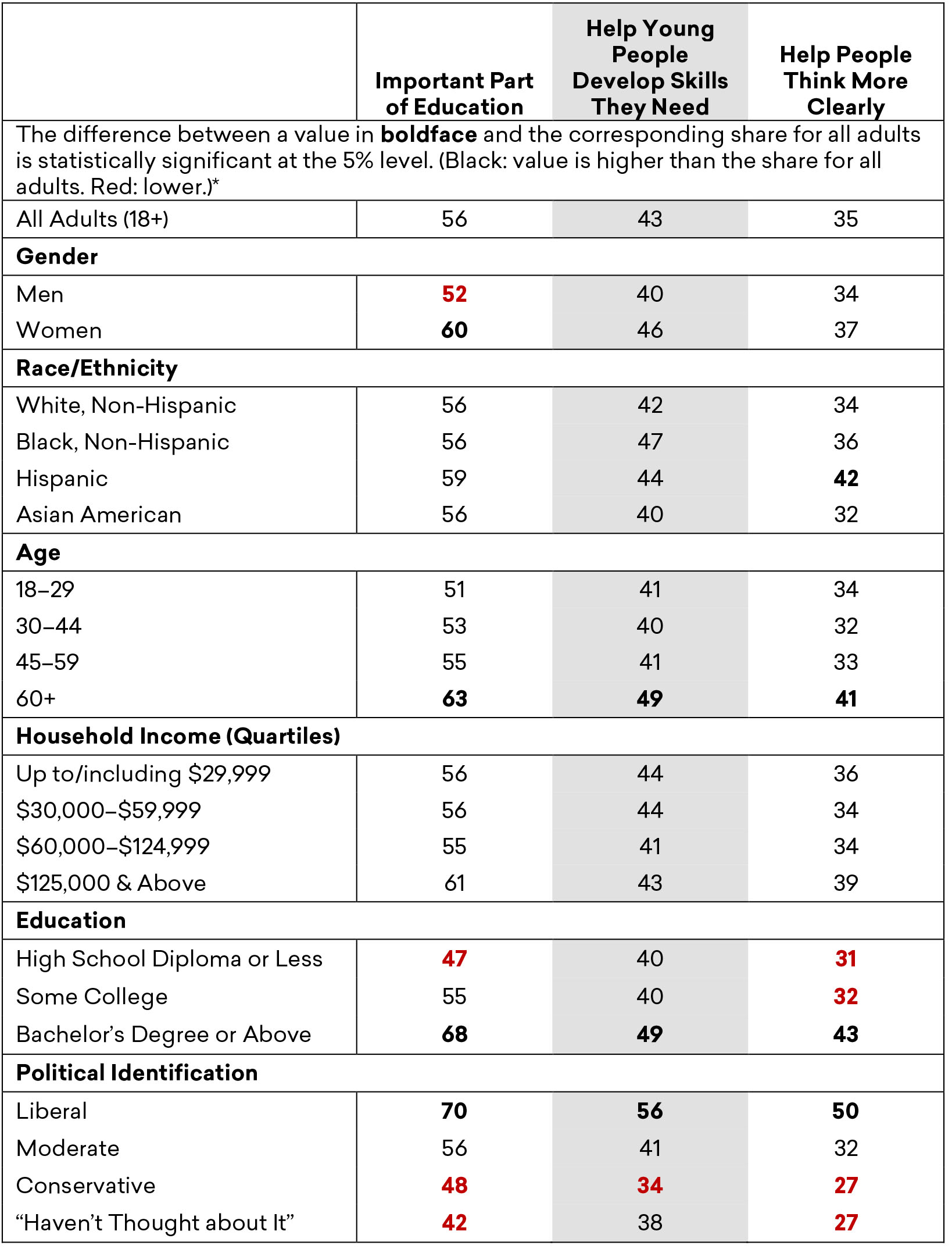

The Educational Benefits of the Humanities

As Figure 2B indicates, statements about the benefits of humanities education were among the most popular with Americans. Of the 16 statements included in the survey, a majority of Americans, 56%, strongly agreed with only one: “the humanities should be an important part of every American’s education.” But 43% of Americans strongly agreed that the humanities help children and adolescents develop skills they need for life, and a smaller share, 35%, strongly agreed that the humanities help people think more clearly. In all three cases, however, 84% or more of Americans agreed at least somewhat that the humanities provide these benefits.

Larger shares of women than men believed that the humanities should be an important part of Americans’ education and that exposure to the field helps young people develop the skills they need (Figure 2D). Hispanics were somewhat more likely than White Americans to believe that the humanities help people think more clearly.

* Not every observed difference between demographic groups (e.g., between the youngest adults and those age 60+, or between Asian and White Americans) is statistically significant at the 5% level. The report narrative discusses notable differences that were found to be statistically significant.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

Older Americans (age 60 and above) were more likely than younger adults to strongly agree with all three statements. And Americans with a bachelor’s degree were also more likely than those with less education to believe that the humanities confer educational benefits. The gap in perception was particularly striking in the case of the statement dealing with the general importance of humanities education. While almost 70% of college graduates strongly agreed with this sentiment, less than one-half of those with a high school education did so.

Political identity was also highly predictive of Americans’ belief in the educational value of the humanities. Liberals were substantially more likely to strongly agree with each of the education-related statements than either conservatives or the apolitical.

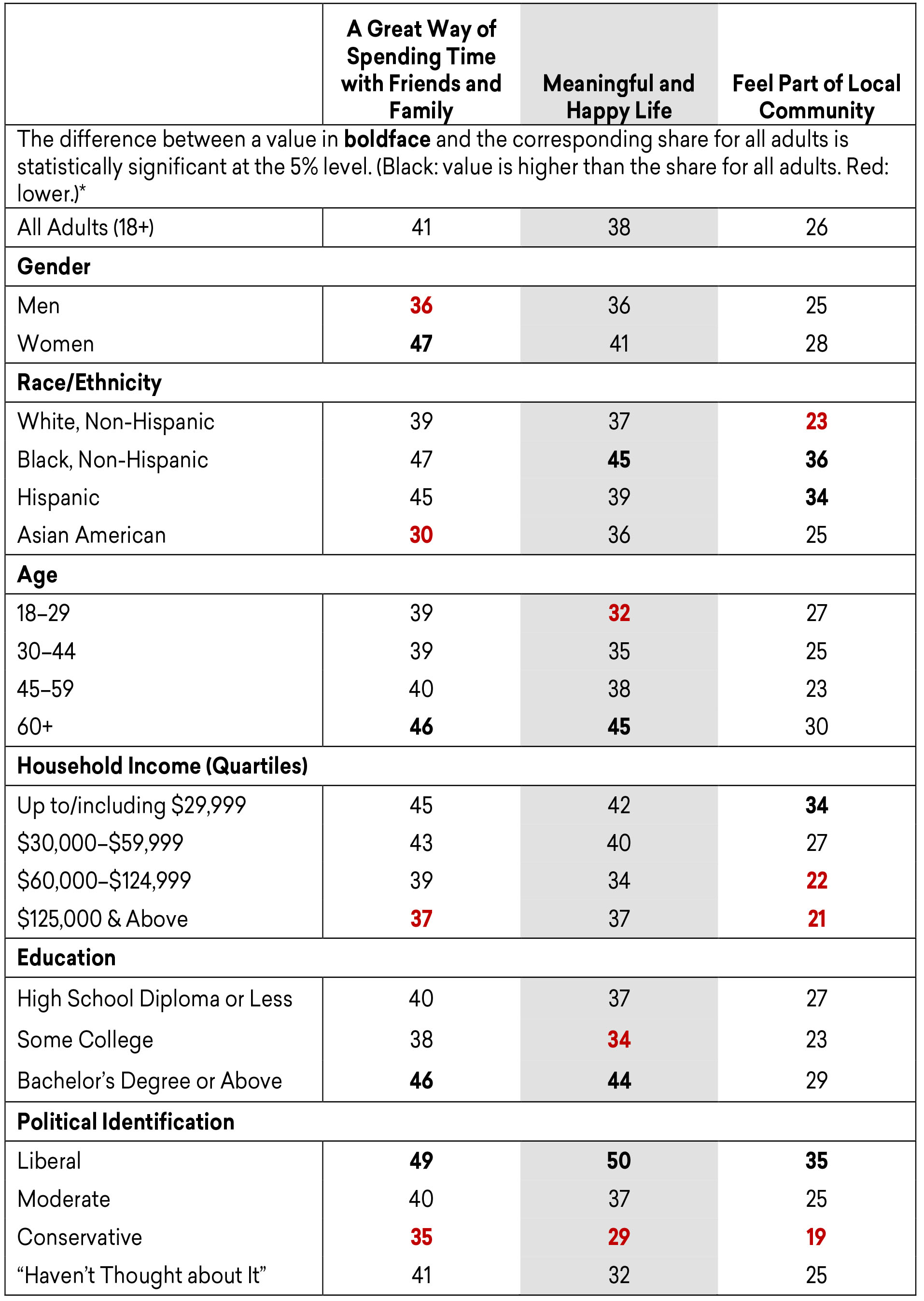

The Personal Benefits of the Humanities

Alongside the perceived educational benefits of the humanities, large majorities of Americans at least somewhat agreed that the humanities provide a range of personal benefits. Among those who strongly agreed, 41% embraced the idea that the humanities were a “great way of spending time with friends and family,” and a similar share (38%) supported the idea that the humanities “make for a more meaningful and happy life” (Figure 2E). Only about one-quarter, however, strongly agreed that the humanities helped them “feel part of [their] local community.”

* Not every observed difference between demographic groups (e.g., between the youngest adults and those age 60+, or between Asian and White Americans) is statistically significant at the 5% level. The report narrative discusses notable differences that were found to be statistically significant.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

Women were somewhat more likely than men to strongly agree that the humanities were a great way to spend time and also make for a better life, and Americans with at least a bachelor’s degree were more likely than those with less education to strongly agree with these two sentiments.

Differences among racial/ethnic groups were found for all three statements. Black Americans were more likely to strongly agree with each statement than Whites. The difference between the two groups was particularly pronounced for the statement that the humanities help one “feel part of the community.” While more than one-third of Black Americans—as well as Hispanics—strongly agreed, less than one-quarter of White Americans agreed that wholeheartedly. Asian Americans were substantially less likely than Blacks and Hispanics to feel that the humanities were a great way of spending one’s leisure time.

The oldest Americans were more likely than the youngest to embrace the propositions that the humanities are a great way of spending time and also make for a good life. The difference was more pronounced in the case of the latter statement. While only 32% of Americans ages 18 to 29 strongly agreed that the humanities added meaning and happiness to life, 45% of those 60 and older did.

Responses to the “great way of spending time” and “feel part of local community” statements diverged along income lines, with Americans in the upper two categories of the income distribution less likely than the least affluent Americans to agree strongly. The disparity was greater with respect to the humanities promoting a sense of community, as only about 20% of the highest-income Americans strongly agreed, in comparison to over one-third of the lowest-income Americans.

Liberals were substantially more likely to strongly agree with each of these propositions than moderates and conservatives. There was a difference of 14 percentage points between liberals and conservatives in the shares of those who strongly agreed that the humanities hold value when spending time with friends and family (with 49% of liberals but only 35% of conservatives strongly agreeing). There was an even larger difference—of 21 percentage points—between the two political sides in the shares of those who strongly agreed the field supported a meaningful and happy life (which had strong assent from 50% of liberals compared to 29% of conservatives). These differences reflect greater ambivalence among conservatives, however, not substantial levels of disagreement. Less than 18% of conservatives disagreed (somewhat or strongly) with either statement. With one exception (that the humanities are “a great way to spend time with friends and family”), liberal Americans were also more likely than apolitical adults to strongly agree with the propositions.

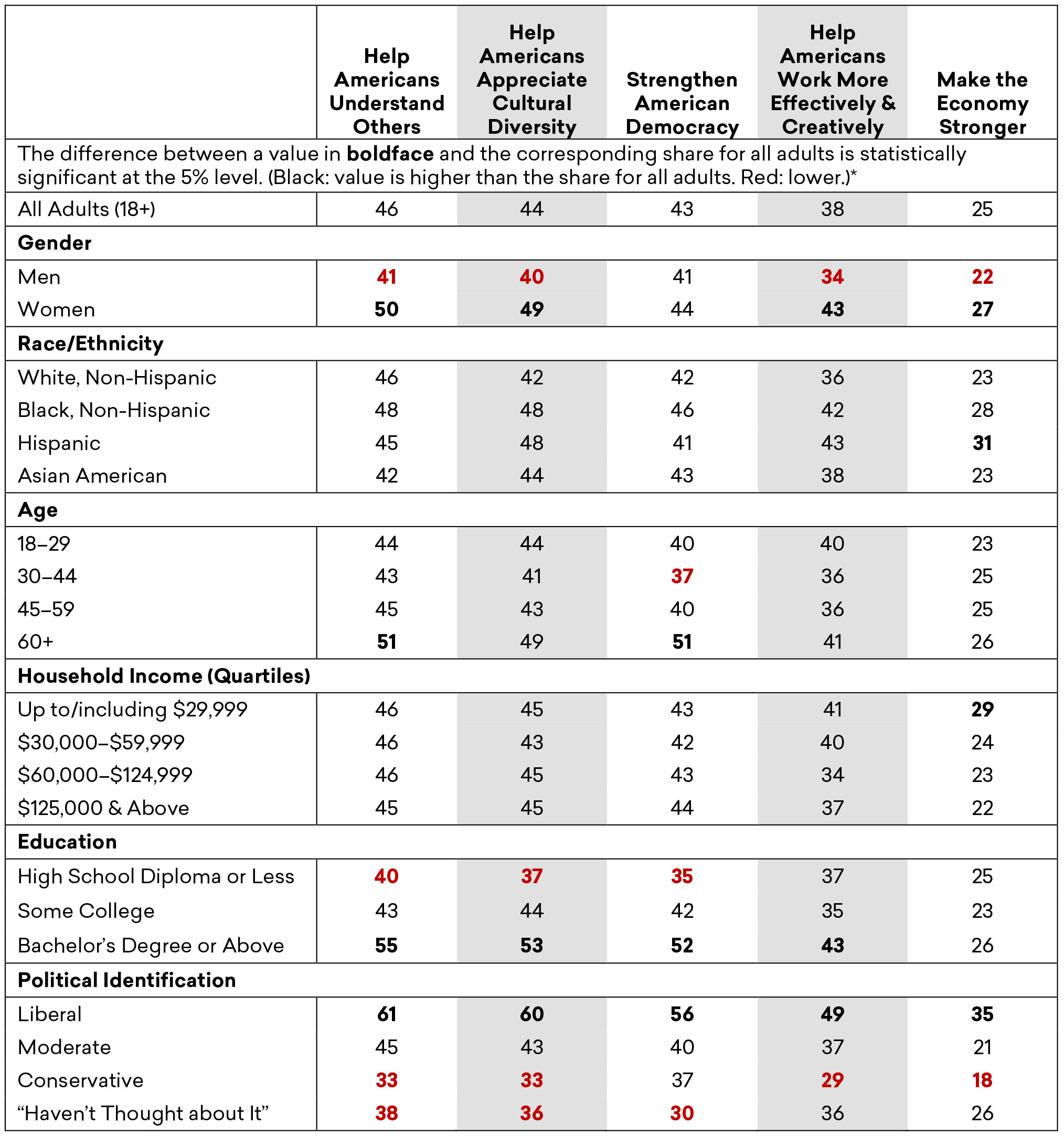

The Societal Benefits of the Humanities

Alongside the educational and personal benefits ascribed to the humanities by most Americans, the survey found that most Americans believed the field contributes a variety of societal benefits. As shown in Figure 2B, around 90% of Americans agreed at least somewhat that the humanities help one understand people whose lives are different from their own and to appreciate cultural diversity. Slightly smaller shares (around 85%) thought the humanities strengthen the nation’s democracy and aid Americans in working more effectively and creatively. Despite the latter perception, a considerably smaller share of Americans (73%) thought the humanities help strengthen the economy.

As Figure 2F indicates, the share of the adult population that expressed strong agreement with each statement is substantially smaller than the shares that expressed at least some agreement (as depicted in Figure 2B), ranging from 25% for “make the economy stronger” to 46% for “help Americans understand others.” In most cases, there was a gender divide. On every item except the statement about American democracy, the share of women who strongly agreed was at least 20% larger than the share of men.

* Not every observed difference between demographic groups (e.g., between the youngest adults and those age 60+, or between Asian and White Americans) is statistically significant at the 5% level. The report narrative discusses notable differences that were found to be statistically significant.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

The analysis found modest differences between racial/ethnic groups on three of the statements. Black Americans were somewhat more likely than Whites to strongly agree that the humanities help Americans appreciate cultural diversity. Blacks, joined by Hispanic Americans, were also more likely to embrace the notion that the humanities help Americans work more creatively and effectively. And a larger share of Hispanics than White Americans strongly agreed that the humanities make the economy stronger.

The oldest Americans were more likely than those ages 18 to 59 to strongly agree that the humanities promote mutual understanding. They were also more likely than those in every other age bracket to feel strongly that the humanities bolster American democracy.

On the two statements related to the economy, modest income effects were also evident, with the least affluent Americans more likely than those who were substantially better-off to believe that the humanities boost the economy and make for more creative and effective workers.

Education was predictive of strong agreement on all but one of these statements; namely, that the humanities make the economy stronger. College graduates were more likely to agree strongly with these statements, particularly those about the humanities promoting understanding, appreciation for diversity, and democracy. The share of college graduates who strongly agreed with each of these statements was about 15 percentage points larger than for those with a high school education or less.

Finally, the political divide evident on other statements carried over to every one of these propositions. The widest separation was on the statement about the humanities making the economy stronger, as the share of liberals who strongly agreed was nearly twice the share of conservatives. The statements about whether the humanities help Americans understand others or appreciate cultural diversity were also marked by a wide gulf. About 60% of liberals strongly agreed with both propositions, but just one-third of conservatives held similar views. For every one of these statements, liberals were also substantially more likely to express strong agreement than apolitical Americans.

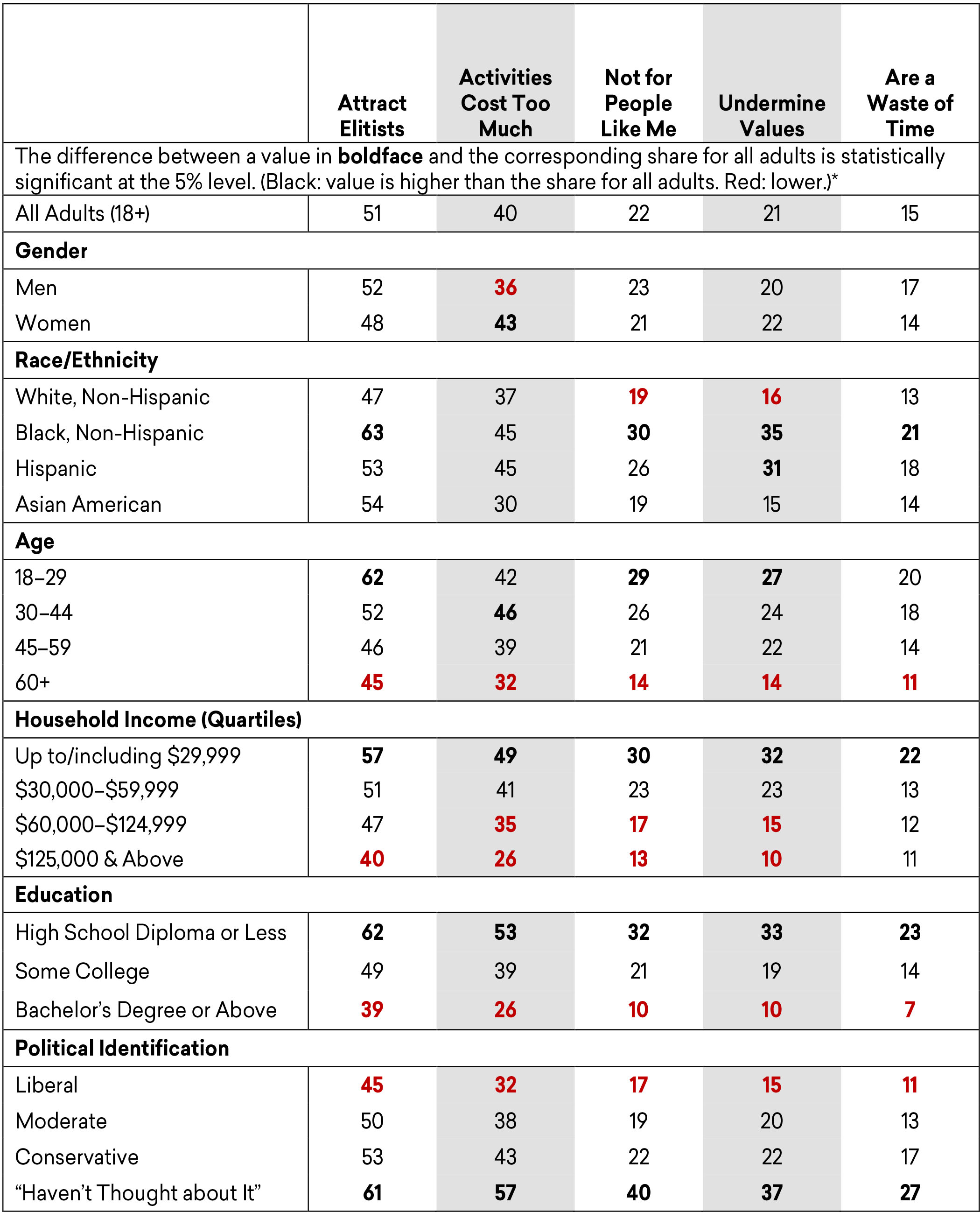

Doubts about the Humanities

While the survey indicates that many Americans ascribed a wide array of positive benefits to the humanities, a substantial share of the public also agreed at least somewhat with several negative statements about the field. As Figure 2B indicates, Americans were most likely to agree, by a substantial margin, that the humanities attract people who are pretentious and elitist (51%) and that humanities activities cost too much (40%). In both cases, however, only a small share strongly agreed with each statement (12% and 8% respectively). Given the relatively small shares of Americans who agreed with the negative statements, the following analysis differs from the previous items. It examines the demographics of those who somewhat agreed as well as those who strongly agreed. Examining this combination was necessary because the share of those who strongly agreed was so small as to severely complicate efforts to take an in-depth look at the demographic patterns.

Americans who were Black, younger, or in lower income brackets, as well as those who lacked a college education or were apolitical were substantially more likely than adults generally to agree with most or all of the negative statements (Figure 2G). The analysis also revealed several notable between-group differences. For instance, liberals were less likely than conservatives and the apolitical to agree with every one of the statements. And a clear gender divide was found for one statement: women were more likely than men to agree that humanities activities cost too much.

* Not every observed difference between demographic groups (e.g., between the youngest adults and those age 60+, or between Asian and White Americans) is statistically significant at the 5% level. The report narrative discusses notable differences that were found to be statistically significant.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

Blacks were more likely than Whites to agree with every negative statement. On the statements about humanities activities costing too much or the field undermining one’s values, Hispanics joined Blacks in being likelier than Whites—and Asian Americans—to strongly agree. A key difference between Blacks and Hispanics is that the former group was more likely to believe that the field attracted elitist and pretentious people.

As indicated above, the statement that the humanities “attract people who are somewhat elitist or pretentious” elicited the highest level of support. Over 60% of Black Americans, Americans ages 18 to 29, the apolitical, and Americans without any college education agreed with this statement. Fifty-seven percent of Americans with household incomes below $30,000 also agreed with this statement. The Humanities Indicators staff encountered substantial disagreement among field stakeholders about the implications of these findings. Some stakeholders observed that this statement spoke only about attractions and tendencies and was not a comprehensive statement about the field or people who lead or attend humanities activities (e.g., “people who engage in the humanities are elitist and pretentious”). Staff noted this as a consideration for interpretation and for potential future iterations of the survey.

The finding that Black Americans were more likely than adults in general to agree with all but one of the negative statements about the humanities is notable, given that Blacks are underrepresented in most academic humanities programs.13 But additional research will be needed to determine whether the two phenomena are causally linked, as perception of the field is but one of several factors that might explain the paucity of Black Americans pursuing humanities degrees. That 35% of Black Americans concurred with the proposition that the humanities “undermine the values of my community” is also striking in view of the finding (discussed in Chapter 1) that Black Americans were more likely to be among the most engaged with activities in the field.

Americans with a college education were substantially less likely to hold negative views about the humanities, but the share who agreed with the negative statements varied by college major. Americans with a college degree in the humanities were less likely than college graduates in general to affirm most negative statements about the field (though nearly one-third of humanities graduates—a share statistically indistinguishable from that for college graduates generally—agreed that it attracts people who are elitist or pretentious). Graduates from engineering and computer science programs were more likely than college graduates in general to agree with the statements about elitism, humanities being “a waste of time,” and the field “not being for people like me” (though each of the latter two sentiments received assent from less than 16% of engineering and computer science graduates).

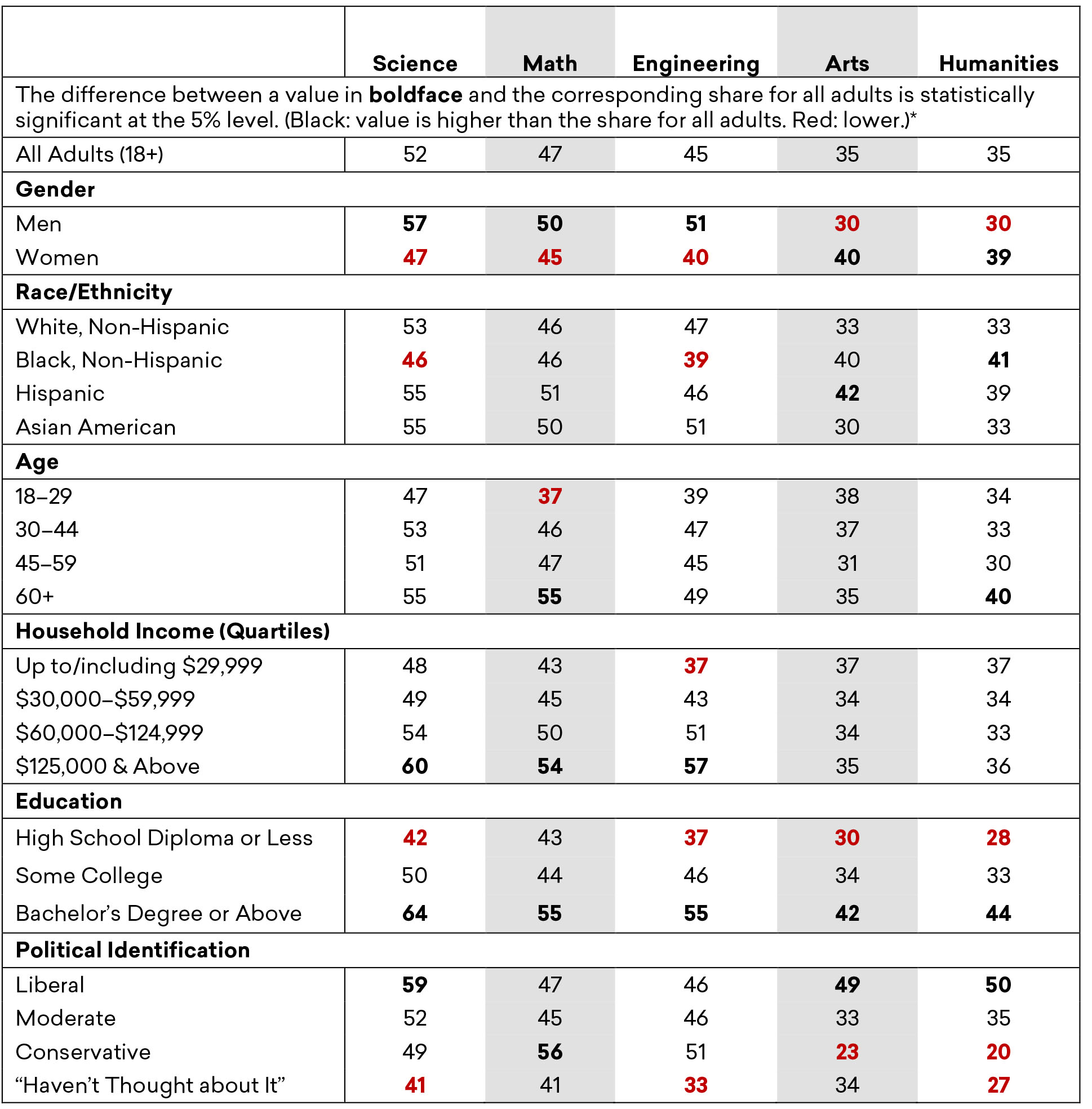

The survey also asked another type of perception question, soliciting reactions to certain field and discipline names. The humanities stood out among the fields for the relatively small share of Americans who held a very favorable opinion when it was reduced to a single word—even after the term had been defined for them (Figure 2H). On this measure, American attitudes about the humanities and the arts were similar, both in the shares of Americans with very favorable impressions of the two terms and in the differences among demographic groups.

* Not every observed difference between demographic groups (e.g., between the youngest adults and those age 60+, or between Asian and White Americans) is statistically significant at the 5% level. The report narrative discusses notable differences that were found to be statistically significant.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

Black and Hispanic Americans were somewhat likelier than Whites to react very favorably to both humanities and arts, and women were more likely than men to have a very favorable reaction to the terms. This contrasts with the STEM field names, where men reacted more favorably than women. For example, 57% of men had a very favorable impression of science, while only 47% of women did. More support for STEM was also found among higher-income Americans than among the less affluent, while arts and humanities elicited similar levels of strong support across all income categories.

The only notable point of contrast between humanities and arts was that age was not predictive of Americans’ impressions of the term art, but the oldest Americans (age 60 and above) were somewhat more likely than younger adults to have a strongly favorable impression of humanities.

The differences by education level that were evident in Americans’ responses to positive and negative statements about the humanities were also found in their responses to the various field names. Americans with college degrees were more likely than less educated Americans to have a positive impression of humanities (and every other field name), but even among college graduates, the share having a very favorable view of humanities (and arts) was below 45%.

Liberal Americans were more likely than conservatives to have a very favorable impression of humanities, arts, and science (but not of the other STEM field names). For arts and humanities, however, the gaps (26 percentage points for the one; 30 percentage points for the other) between liberals and conservatives dwarfed the gap for science (10 percentage points). Liberals were also considerably more likely than the apolitical to have a favorable impression of arts and humanities.

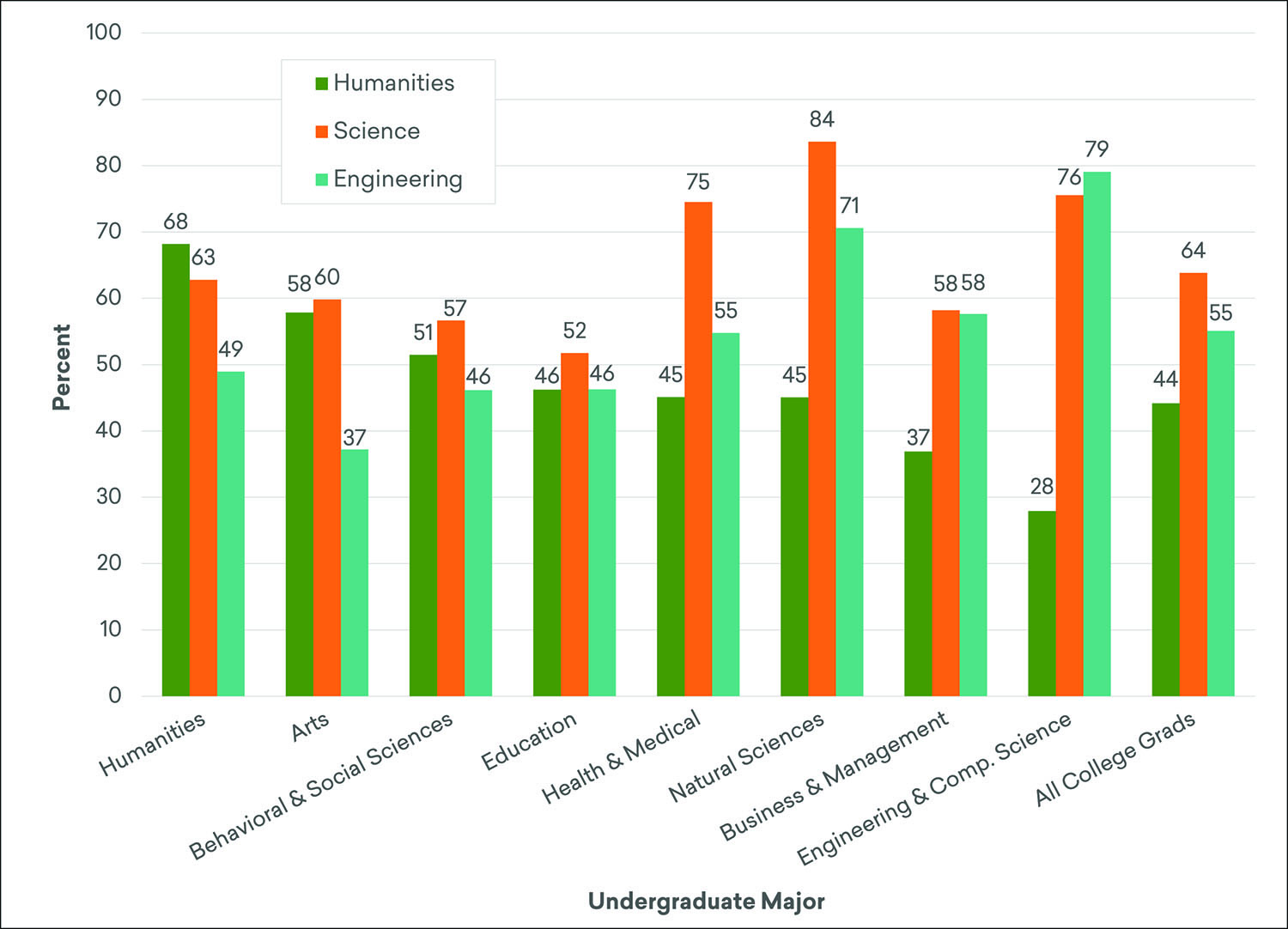

Almost 70% of humanities graduates held very favorable views about the humanities, a larger share than graduates from every other field except the fine and performing arts (Figure 2I; the difference between the humanities and arts depicted in the graph was not found to be statistically significant). Only 28% of engineering and computer science graduates had as favorable an impression of humanities, a smaller share than every other comparison field. Conversely, less than half of humanities graduates had a very favorable impression of engineering (smaller than the shares of engineering and natural science majors who held that view). And while 63% of humanities majors held very favorable views of science, that percentage was smaller than the share of graduates from the natural sciences who were as kindly disposed toward the term.

* Majors are listed in descending order by the size of the share having very a favorable impression of the humanities. Not all observed differences between majors are statistically significant. Statistically significant differences of note are discussed in the report narrative.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

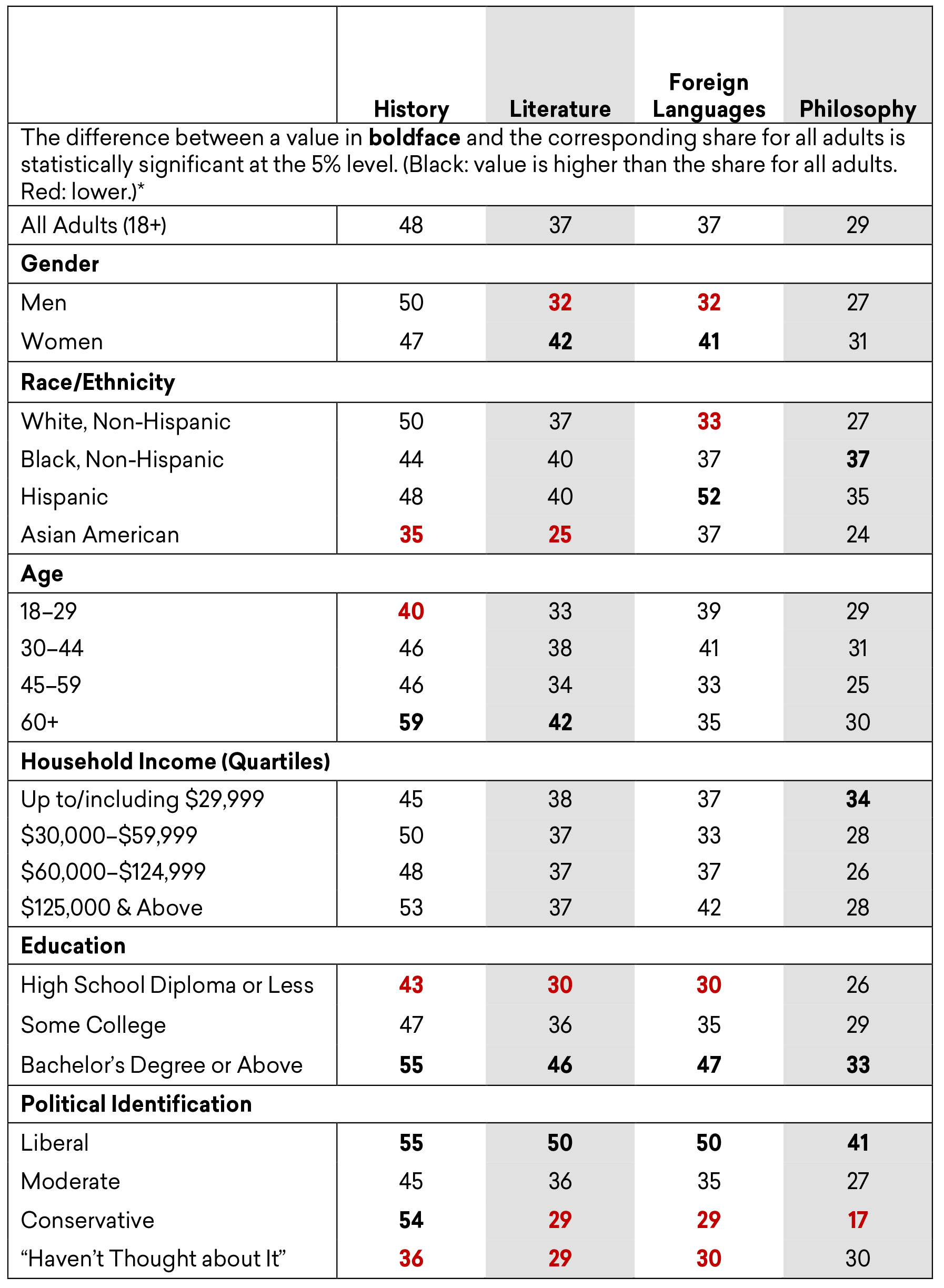

As with the term humanities, the study found notable differences among demographic groups’ impressions of the field’s component disciplines. In line with the findings about reading presented in Chapter 1, a greater of share of women than men had a very favorable impression of literature—and languages—than men (Figure 2J). And older Americans (those age 60 and above), who were substantially more likely than younger adults to engage in history and reading activities, were also more likely to hold very favorable views of history and literature—particularly in comparison to the youngest cohort of American adults (ages 18 to 29).

* Not every observed difference between demographic groups (e.g., between the youngest adults and those age 60+, or between Asian and White Americans) is statistically significant at the 5% level. The report narrative discusses notable differences that were found to be statistically significant.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

A substantial gap separated White Americans’ and Hispanics’ impressions of the term foreign languages,14 with 33% of Whites holding a very favorable impression, compared to 52% of Hispanics. Differences between racial/ethnic groups were also found for history, literature, and philosophy. Asian Americans were substantially less likely than both Whites and the adult population as a whole to have a very favorable impression of the terms history and literature. In the case of literature, the share of Asian American who responded very favorably to the term was also lower than the shares of Black and Hispanic Americans. And while 37% of Black Americans had a very favorable impression of philosophy, only 24% of Asian Americans and 27% of Whites had as favorable an impression.

For two of the disciplines, there were modest differences between the least and the most affluent Americans. In the case of history, those in the top income quartile were more likely to have a favorable view of the term. The reverse was true for philosophy.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given their greater propensity to read fiction and nonfiction, Americans with bachelor’s degrees were more likely than less educated Americans to have a very favorable impression of literature and languages. Americans with college degrees were also more much more likely to have a strongly favorable impression of history. This is notable, in view of the finding (discussed in Chapter 1) that college-educated Americans were only slightly more prone to watch shows with historical content than those with a high school education or less—though college graduates were quite a bit more likely to research the history of something of interest. College graduates were also more likely to have a very favorable reaction to the term philosophy, but the gap between this group and those without any college education was not nearly as large as it was for the other terms.

Some of the largest gaps in enthusiasm for the various field names appeared when results were analyzed by political beliefs. Liberals and conservatives were similar in their enthusiasm for history, and both groups were somewhat more likely than moderates to be very favorably disposed toward the term. For all other terms, however, liberals were substantially more likely than conservatives to have a very favorable impression. The largest gap between the two groups was with philosophy. While 41% of liberals had a very favorable impression of the term, only 17% of conservatives were this favorably disposed to it. For all four terms, liberals were also markedly more likely than the apolitical to have a very favorable impression.

____________________

This chapter summarizes only two of the three perception questions included in the survey. The next chapter takes up questions about the humanities in childhood and education, exploring Americans’ memories of their engagement with the humanities as children, as well as their attitudes about humanities education for young people and their thoughts about which subjects they wish they had studied more while in school. These education-focused findings add nuance to the findings in this chapter about Americans’ general appreciation of the field.