1. Dimensions of the Humanities in Everyday Life

One of the main objectives of the study was to establish the level of public engagement with a mix of humanities activities across a variety of disciplines (art history, history, literature, languages, ethics, and religion). These activities included traditional forms of engagement, such as reading (of fiction or nonfiction) and visiting museums and historic sites, as well as more contemporary forms, such as sharing humanities content through social media and listening to podcasts on humanities subjects.

Working with key stakeholders in the humanities (including leaders of state humanities councils and specialists in the various academic disciplines) the Humanities Indicators staff identified a set of common types of humanistic activity. Unfortunately, space and time considerations meant that not every item suggested by humanities stakeholders could be included in the survey. In the end, 19 items were chosen that captured activities with a high likelihood of engagement while also representing the breadth of the humanities experience. The survey also extended beyond the yes/no format employed by many arts participation surveys to inquire about frequency of engagement.

This chapter is organized into three sections: the first looks broadly at the “what” and “how often” of national engagement with the humanities; the second examines how these forms of engagement relate to one another; and the final section drills down into activity clusters (e.g., consuming humanities content through the media, reading-related activities, and online engagement with humanities through internet searches and sharing on social media), to explore how levels of engagement vary across demographic groups.

The Semi-engaged Public

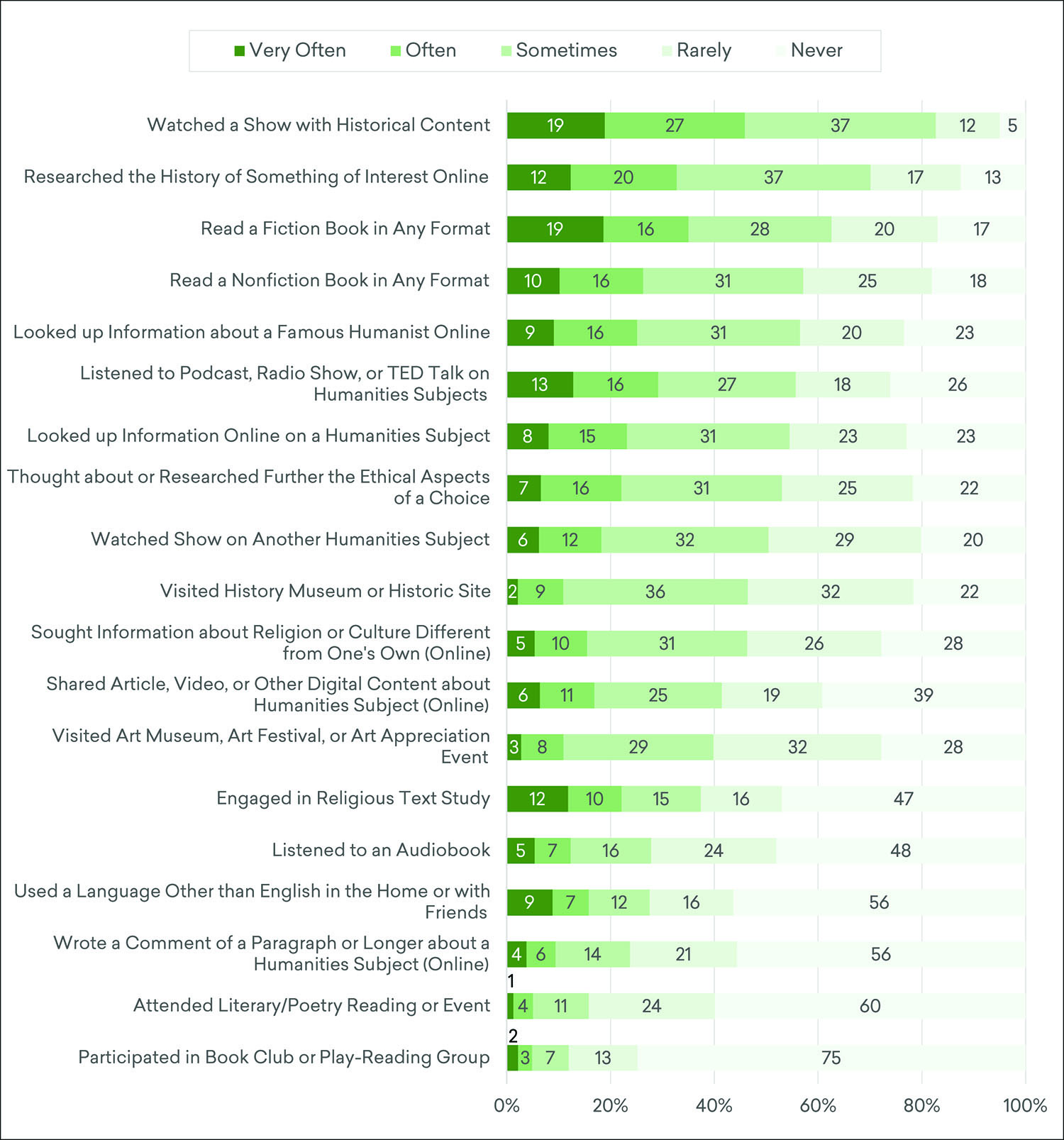

The survey found that most American adults (97%) had engaged in at least one form of humanities activity at least sometimes in the previous year. A majority of the adult population engaged in no single activity often or very often, but the survey found nine activities that at least half of Americans engaged in sometimes or more frequently (Figure 1A). The most commonly practiced activities included consuming humanities-related audio and video content, researching humanities subjects online, and reading fiction and nonfiction books.

The shares of Americans engaging in each of the 19 activities included in the survey differed widely, however. At the high end, 83% of Americans watched shows with historical content at least sometimes; at the low end, 12% participated in book clubs or play-reading groups with the same regularity.

* Activities are listed in descending order by the size of the share who engaged at least “sometimes." The frequency shares for a given activity may sum to 99% or 101% due to rounding.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

Watching shows with historical content (on a TV, computer, or other device) was particularly popular with Americans. Forty-six percent of the adult population—the largest share for any of the activities included in the study—had watched such shows often or very often in the previous 12 months. Among the various activities, watching a history show was also the activity that Americans were least likely to engage in rarely or never, with only 17% of adults doing so that infrequently. The share of Americans who had read works of fiction very often in the previous year (19%) was the same as the share who had watched historical shows at that rate, but the share of Americans who rarely or never read works of fiction was considerably higher (37%).

Activities that required leaving the home tended to have lower levels of engagement.2 Visiting history museums and historical sites was at the upper end of the frequency range for activities that required leaving the home, as 11% of Americans did so often or very often, while another 36% did so sometimes. A similar share of Americans (11%) visited art museums or attended arts events often or very often, but only 29% placed themselves in the “sometimes” category. And while reading was one of the most common types of humanities activity, participation in reading-related activities outside the home—in the form of book clubs or literary events—had the lowest level of engagement in the survey, as only 5% of adults participated in these activities often or very often.

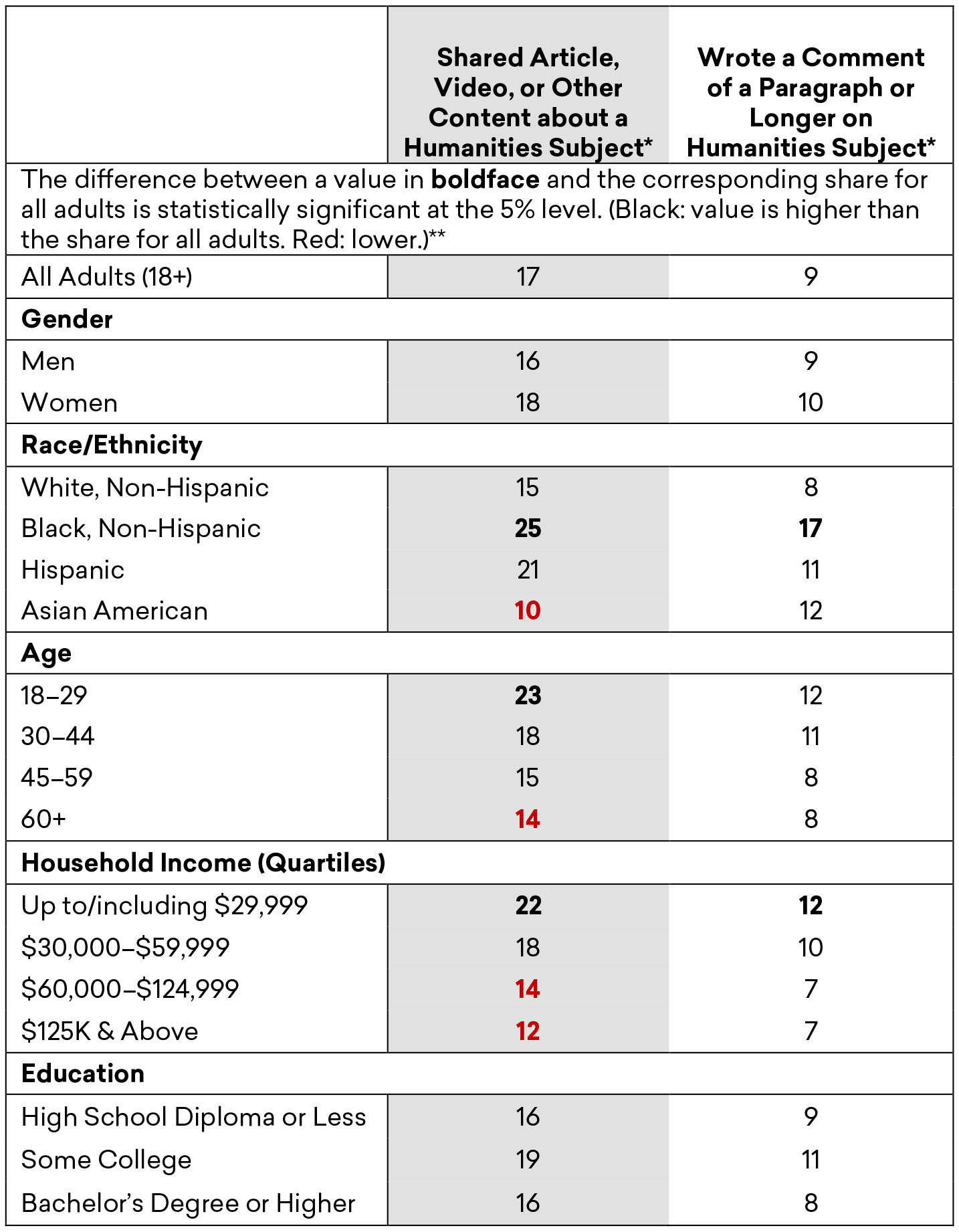

The survey also inquired about online humanities engagement, asking whether Americans had researched various humanities subjects, shared information about these subjects with others, or posted humanities-related commentary of their own. Depending on the subject, 46% to 69% of Americans recalled looking up humanities content at least sometimes in the previous year, and over half had listened to podcasts or other audio content on humanities topics. Researching history topics online was second in popularity only to watching history shows, with just 13% of Americans indicating that they never engaged in this activity. Sharing humanities content or writing about humanities subjects was considerably less common. Almost 60% rarely or never shared, and over three-quarters of Americans wrote about humanities subjects that infrequently.

Who Engages Most Often?

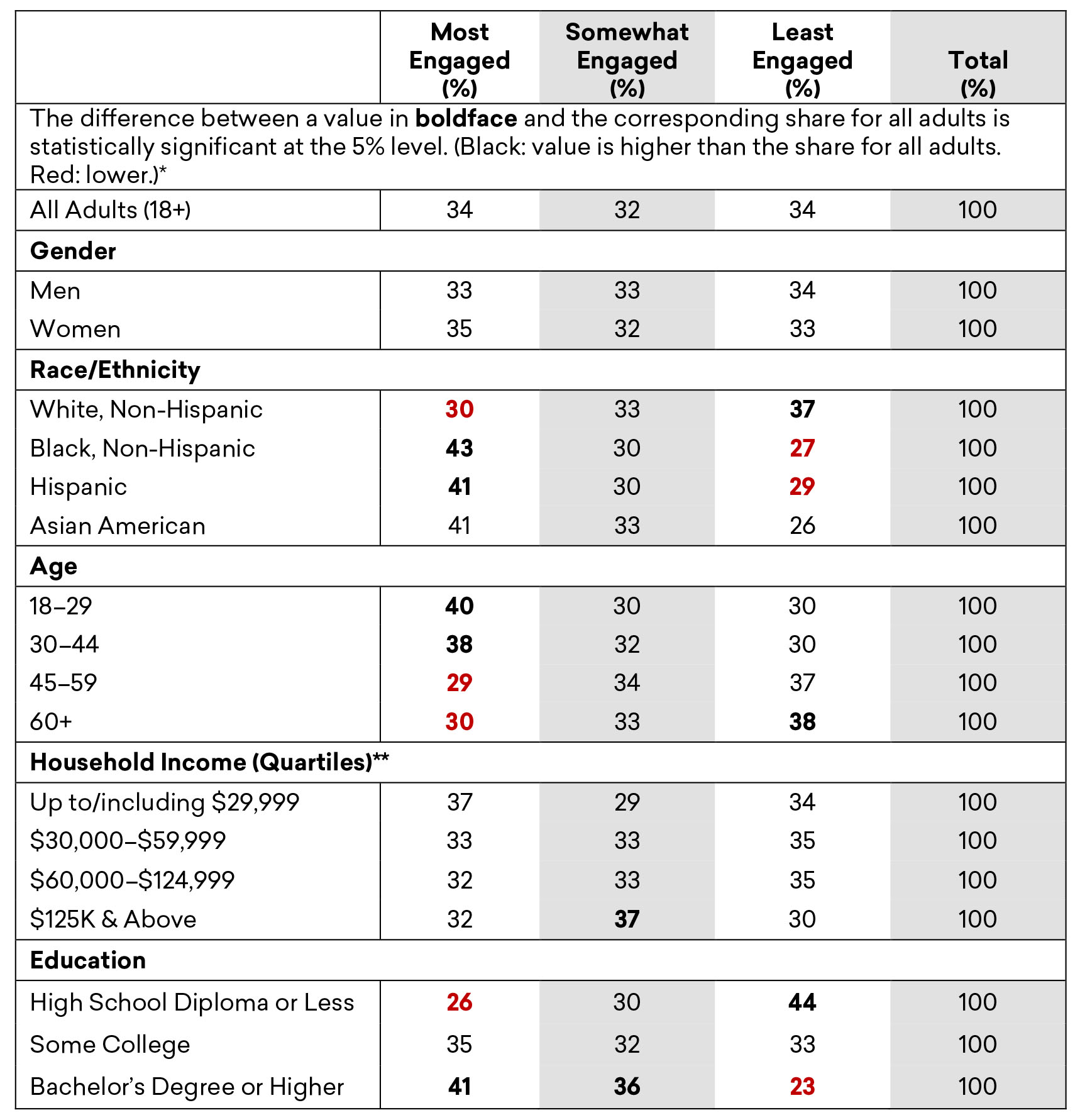

To measure overall engagement with the humanities, each survey respondent was assigned a score based on the number of activities they engaged in and the frequency of that engagement (all activities were weighted equally). Respondents whose scores placed them in the top third of the distribution3 were assigned to the “most engaged” category, and the third with the lowest scores constituted a “least engaged” category. Those with scores between the two poles were labeled “somewhat engaged.” Figure 1B indicates the shares of different demographic groups that fell into each category.

* Not every observed difference between demographic groups (e.g., between the youngest adults and those age 60+, or between Asian and White Americans) is statistically significant at the 5% level. The report narrative discusses notable differences that were found to be statistically significant. The “most”/“somewhat”/“least” shares for a given demographic group may sum to 99% or 101% due to rounding.

** Approximate. The income data collected by the survey were categorical and did not align exactly with the 2018 income quartile estimates published by the US Census Bureau (the most recent available when this analysis was being conducted).

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

Figure 1B, like many others in the report, highlights where a difference between a demographic group and all American adults was found to be statistically significant at the 5% level.4 The narrative goes further and discusses instances in which particular demographic groups (e.g., young adults, Americans with college degrees, etc.) were more or less likely than other such groups to have participated in a particular humanities activity or to have expressed a certain view of the field.

As Figure 1B shows, gender was not predictive of overall engagement in the humanities, but race was salient. Black and Hispanic Americans were more likely than White Americans to have been among the most engaged with the humanities. In the case of Black Americans this is attributable to their higher rates of religious text study, online activity, and participation in literary events. Hispanics were also more likely than White Americans to have attended literary events and much more likely to report speaking a language other than English with family and friends.

Age also proved to be an important factor in humanities engagement, as younger Americans were more likely than middle-age and older Americans to be among the most engaged. While approximately 40% of Americans ages 18 to 44 were among the most engaged, less than a third of those 45 and older were in this category.

The relationship of income to engagement was modest and less straightforward. The highest income Americans were more likely to be somewhat engaged than the lowest-income Americans, who were more concentrated at the poles of the engagement scale.

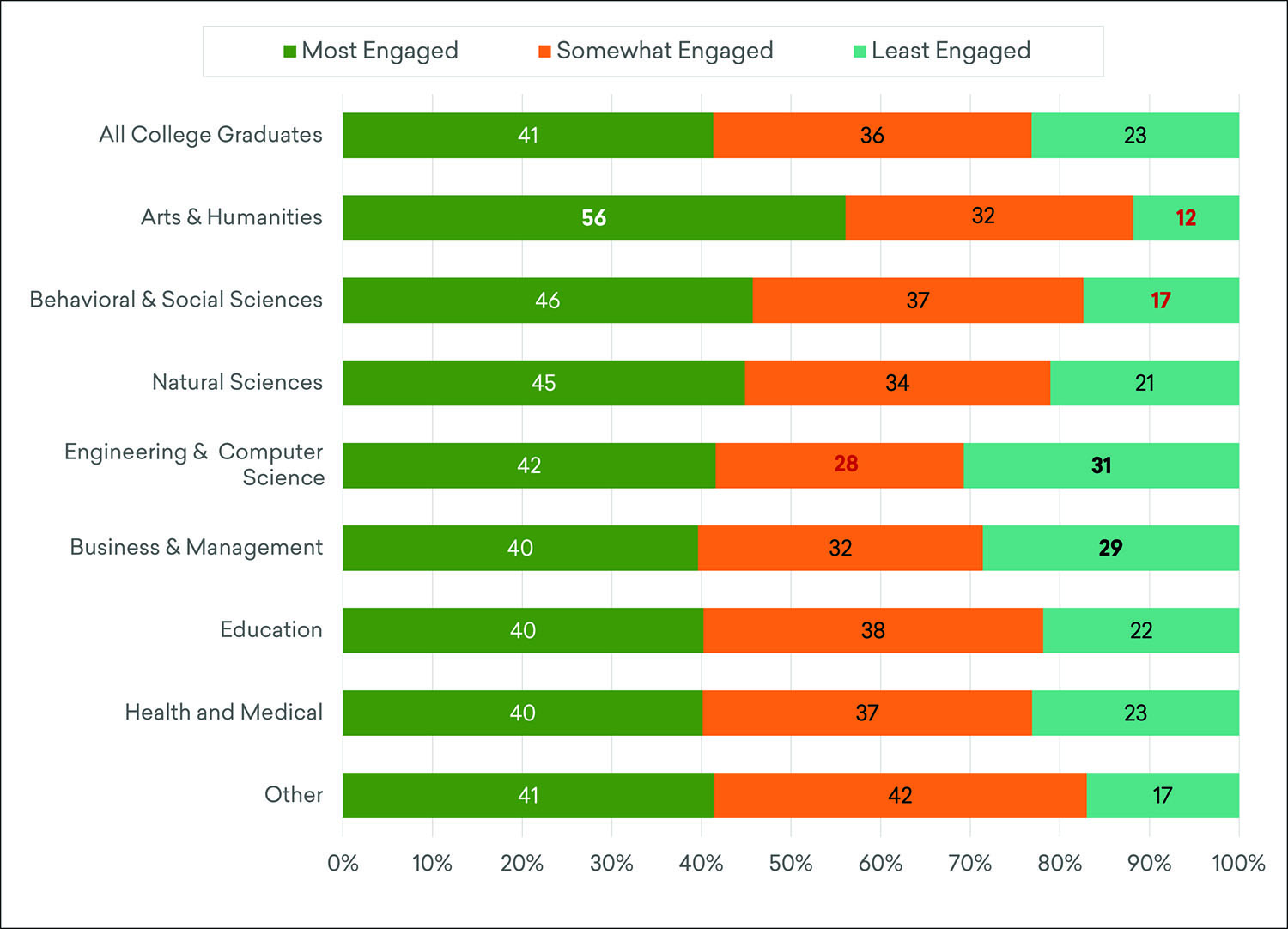

Additionally, education was found to be strongly related to overall humanities engagement. Only 26% of Americans with a high school education or less were among the most engaged, compared to 41% of college graduates. Disaggregating the college-educated population by undergraduate major revealed that arts and humanities majors were more likely than college graduates in general to have engaged with the humanities (Figure 1C). Focusing in on specific majors, fifty-six percent of arts and humanities majors fell into the “most engaged” category, compared to 40–46% of graduates from every other field.

* The difference between a value in boldface and the corresponding share for all college graduates is statistically significant at the 5% level. (Black/White: value is higher than the share for all college graduates. Red: lower.) Not all differences between individual majors are statistically significant at the same level. The report narrative discusses notable between-major differences that were found to be statistically significant. The “most”/“somewhat”/“least” shares for a given major may sum to 99% or 101% due to rounding.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

Business majors were more likely than college graduates in general to be among the least engaged. So were majors in engineering and computer science. The share of arts and humanities majors in the “least engaged” category was statistically significantly smaller than for every other major examined, with the exception of behavioral and social sciences.

Relationships among the Activities

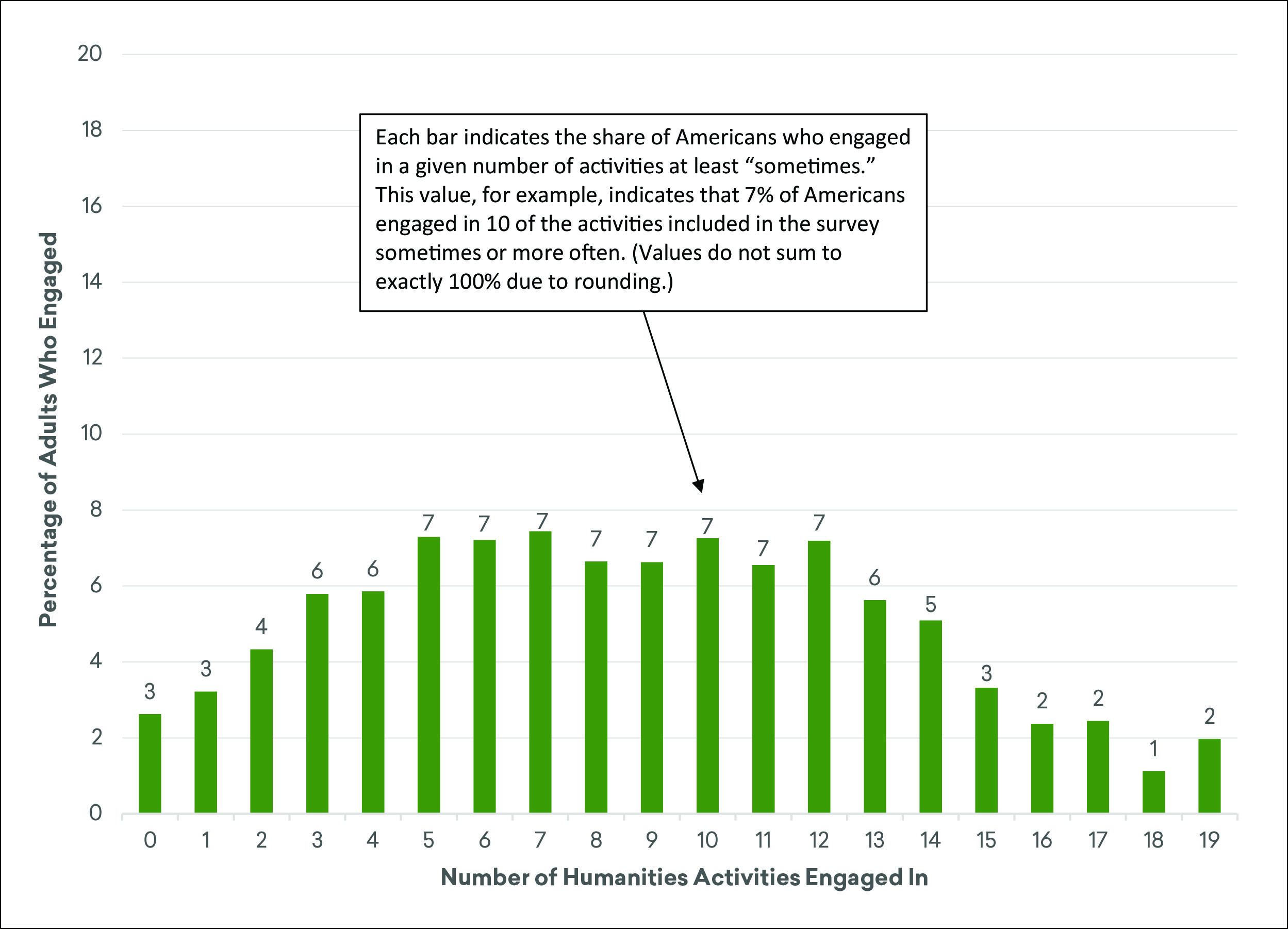

As noted above, virtually every American engaged in at least one form of humanities activity in the year preceding the survey, and further analysis indicates that a substantial share of Americans engaged in multiple humanities activities with some regularity (Figure 1D). Approximately three-quarters of Americans engaged at least sometimes in five or more activities. Just over half of Americans engaged often or very often in three or more activities.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

Translating the distribution above into average activity counts, American adults engaged at least sometimes in an average of nine activities, and more frequently (“often” or “very often”) in four.

A key question the survey sought to answer was how these various forms of engagement relate to one another in the daily lives of Americans. Do people who read also pursue other forms of humanities activity? Do the millions of Americans who watch shows with historical content engage with history in other ways, such as visiting historical sites? To probe these issues, the strength of association among activities was explored using both correlation and factor analysis.5

One of the most striking findings from this analysis was that some of the most popular forms of humanities engagement were only weakly associated with the other activities. For example, the most common form of humanities engagement, watching shows with historical content, had only a weak relationship to every other form of activity in the survey, except watching shows on other humanities subjects. Similarly, fiction reading had a limited association with every other form of humanities activity in the survey except nonfiction reading.

These findings point to the key insight of the analysis: related activities tended to cluster by mode of engagement (e.g., online research versus visits to cultural institutions) rather than by the substance or content of that engagement (literature or history, for example). The analysis identified five such mode-based groupings of related activities:

- watching humanities content on TV or other devices;

- conducting research on the internet about humanities subjects;

- reading books (fiction and nonfiction);

- sharing or commenting on humanities content online; and

- visiting cultural institutions (art/history museums and historic sites).

The relationships among the activities in each of the above groupings were strong, while the relationships between the activities in one cluster and those in the others were only moderately strong or quite weak. In sum, the study found that “doing the humanities” for most Americans involves only a portion of the full portfolio of activities that can be thought of as humanities-related, and that what links the activities in which people engage is more how they are done than their substantive focus.

In the following sections, the report discusses clusters of activities that are related conceptually, but often cut across the different modalities noted above (e.g., “Reading”, a cluster that includes reading fiction and nonfiction, but also listening to audiobooks, religious text study, and participating in book clubs). While these clusters provide an opportunity to highlight notable variations in patterns of engagement across seemingly related activities, please bear in mind that some of the activities within each cluster are only loosely connected in practice for many Americans. The following analysis will also focus primarily on the share of Americans who often or very often engage in each of these activities, in order to facilitate analysis of differences among demographic groups with respect to their level of participation.

Reading

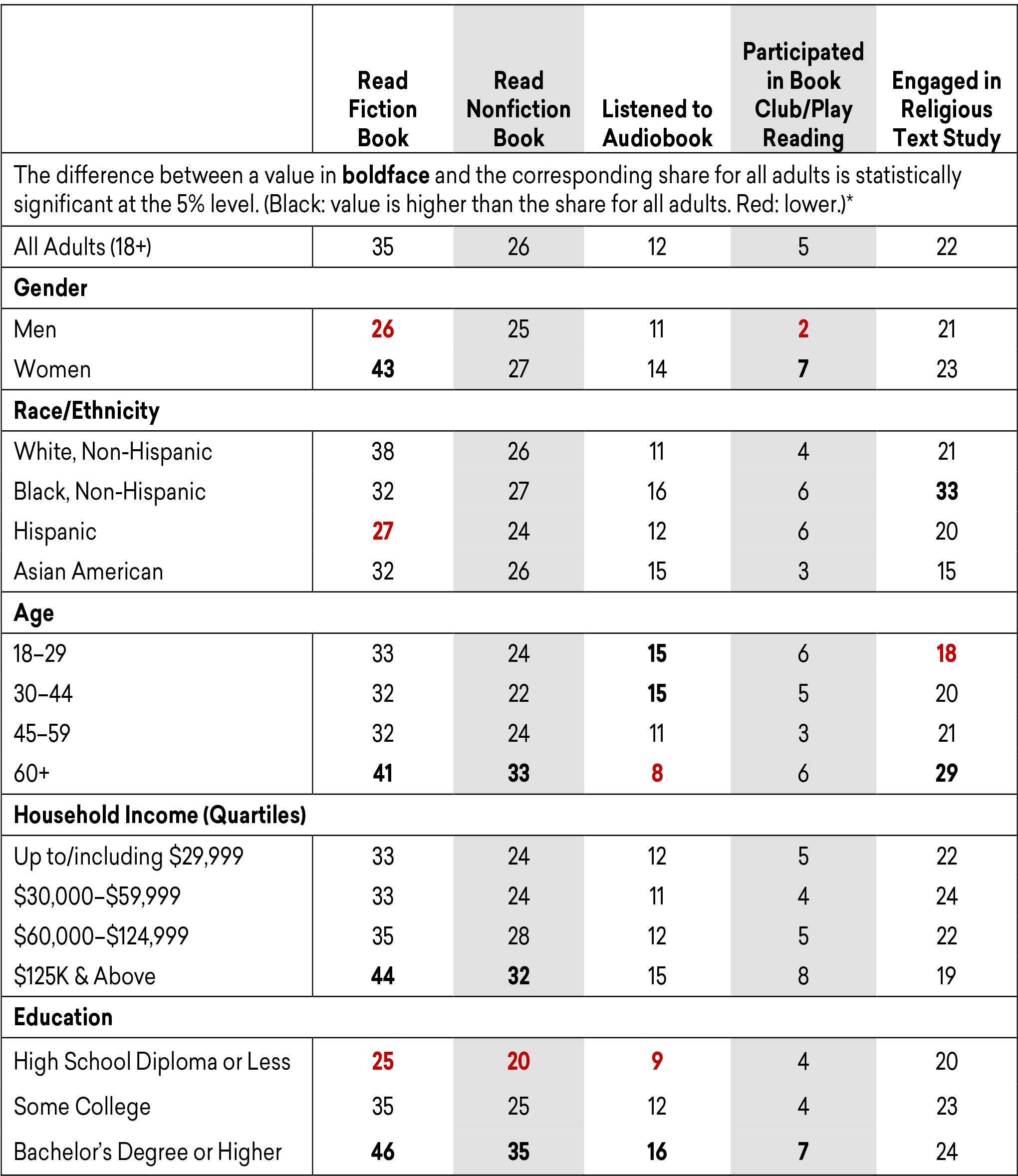

Even though the study found a relatively close relationship between fiction and nonfiction reading, a key difference is who tended to engage in these forms of humanities activity.6 Older, wealthier, and college-educated Americans were more likely than others to engage in both types of reading, but the genres differed in their popularity with women.

Previous studies have shown that women are much more likely to read fiction books than men, and this becomes even more obvious when the frequency of this activity is considered.7 The survey found that 43% of American women had read fiction often or very often in the preceding year, while only 26% of men had read in the genre at a similar rate (Figure 1E). However, the study did not find as much of a difference between men and women when it came to reading nonfiction. This was due to a markedly smaller share of women reading nonfiction than fiction. The share of men who often read fiction was similar to the share who read nonfiction (approximately one-quarter), while the share of women who read nonfiction (27%) was 16 percentage points smaller than the share who read fiction. The share of women who rarely or never read nonfiction was also 12 percentage points larger than it was for fiction (41% for nonfiction compared to 29% for fiction).8

* Not every observed difference between demographic groups (e.g., between the youngest adults and those age 60+, or between Asian and White Americans) is statistically significant at the 5% level. The report narrative discusses notable differences that were found to be statistically significant.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

The data also reveal that Hispanic Americans were less likely than Whites to read fiction frequently. Though the two groups read nonfiction with about the same frequency, the share of Hispanic Americans who often or very often read fiction was nine percentage points smaller than that for Whites.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, an analysis of reading by college major revealed that humanities majors were much more likely to be readers of fiction and nonfiction than college graduates in general. Almost two-thirds of humanities graduates read fiction often or very often, compared to 47% of college graduates generally. Humanities majors were more likely to read fiction than majors in every other field except education. The contrast with engineering and computer science majors was particularly pronounced, as less than one-third of graduates from those fields read fiction often.

Nearly half (49%) of humanities graduates read nonfiction often or very often, while only 35% of college graduates engaged with nonfiction this regularly. Graduates from five fields (behavioral and social sciences, business and management, education, engineering and computer science, and health and medical) were less likely to read nonfiction than humanities majors, as only around one-third of graduates from each of these fields read in this genre often or very often.

Twelve percent of Americans listened often or very often to audiobooks (and another 16% listened sometimes). The analysis of the relationships between activities described in the previous section revealed that Americans who listened to audiobooks were also somewhat more likely to be readers of nonfiction than fiction. Reading nonfiction and listening to audiobooks were also, along with fiction reading, activities that college-educated Americans were more likely to engage in than Americans with lower educational attainment. Audiobook use differed from reading of fiction and nonfiction, however, in that it was negatively associated with age. Although only a small share of young people listened to audiobooks, they were still substantially more likely than Americans age 60 and above to have done so. Additionally, Black Americans were found to be slightly more likely than Whites to have engaged with audiobooks on a regular basis.

While Americans’ participation in book clubs and play-reading groups was markedly lower than for reading, this activity was similar to fiction reading in that women were more likely to have participated than men. College graduates were also more likely than those with less education to participate in these activities.

Similar to fiction and nonfiction reading, religious text study was significantly more popular with older Americans: 29% of Americans age 60 or older engaged in this activity often or very often, compared to just 18% of those ages 18 to 29. The salience of education, however, was far less pronounced for religious text study than for either fiction or nonfiction reading.

Black Americans were more likely to have engaged in religious text study than Americans in general, as 33% did so often or very often, compared to just 22% of all Americans. Black Americans were also more likely than whites, Hispanics, and Asian Americans to have engaged often or very often in this humanities activity.

Watching and Listening to the Humanities

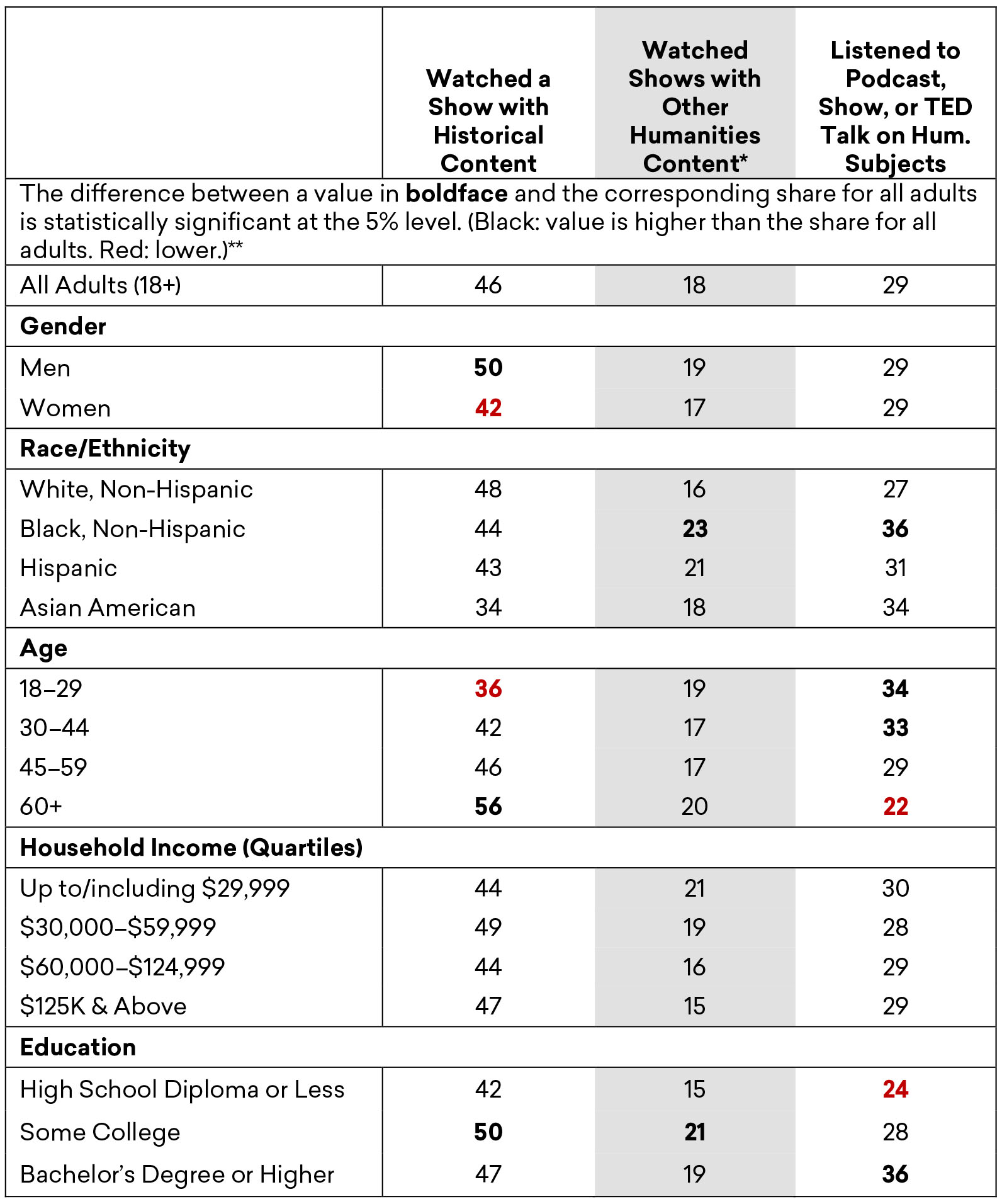

While many Americans engaged with the humanities through reading, the largest share of Americans engaged with the humanities through watching shows with historical content (on TV channels such as the History Channel and PBS or on YouTube or other online platforms). Some 46% percent of Americans watched shows with historical content often or very often, while less than one-fifth did so rarely or never.

Unlike every other humanities activity included in the survey, history show watching attracted a larger share of men than women (Figure 1F). While 50% of men often or very often watched shows with historical content (and 13% did so rarely or never), only 42% of women did so (and more than one-fifth of women rarely or never watched such programming).

* Wording of question is described in narrative.

** Not every observed difference between demographic groups (e.g., between the youngest adults and those age 60+, or between Asian and White Americans) is statistically significant at the 5% level. The report narrative discusses notable differences that were found to be statistically significant.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

Older Americans were substantially more likely to watch history-focused shows than their younger counterparts. Approximately 56% of Americans age 60 and above watched shows with history content often or very often, as compared to just 36% of Americans ages 18 to 29. The survey also detected that Asian Americans were less likely than Whites to often watch such shows.

The study found that a substantially smaller share of Americans watched shows with other humanities content (defined as “art, literature, philosophy, or world religions”). Only 18% of adults often or very often watched shows with this content, and almost half rarely or never watched such shows, although Black Americans were more likely than the adults in general and Whites to do so. And the highest-income Americans were somewhat less likely than those in the lowest income quartile to have watched shows with other humanities content.

Alongside the visual media, the survey found that 29% of Americans often listened to humanities content (defined in the survey instrument for this item as “art, history, literature, philosophy, and world religions”) in the form of podcasts, radio shows, and TED talks. Unlike history show watching, older Americans were less likely than their younger counterparts to be listeners (as only 22% of Americans age 60 and older did so often or very often, and 52% rarely or never listened to humanities content). Also, Black Americans were more likely than Whites (and Americans in general) to listen to shows with humanities content.

All three types of activity in this cluster were at least weakly correlated with education, with Americans who completed at least some college being more likely to have engaged. In the case of listening, the relationship was stronger, with over one-third of college graduates having engaged, as compared to 24% of Americans with a high school education or less.

Seeking the Humanities Online

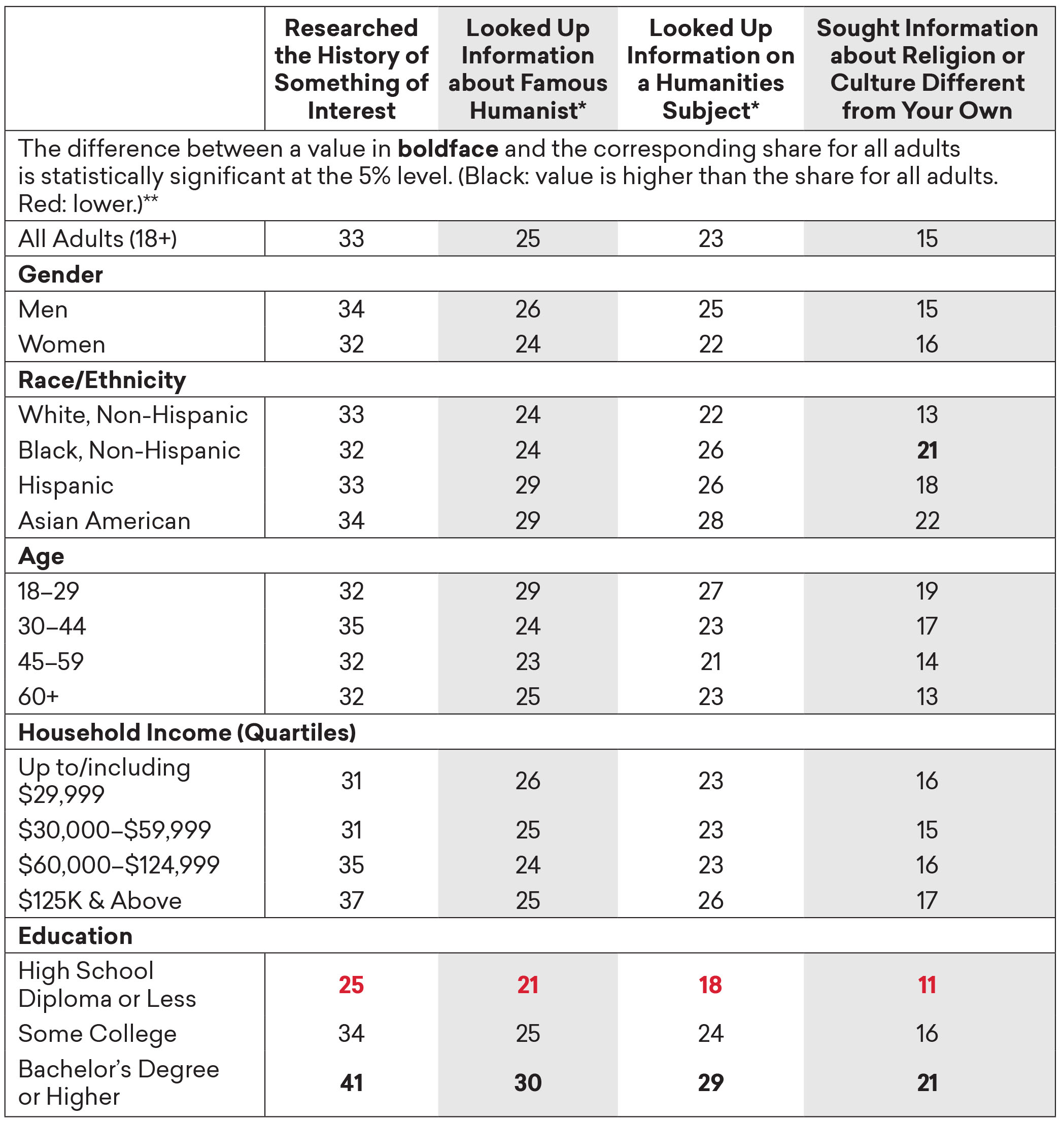

Using the internet as a means of increasing one’s knowledge of the humanities was more evenly distributed across demographic categories than many of the other activities examined in the survey (Figure 1G). Just as for show watching, history was the most popular humanities subject for internet research. Thirty-three percent of Americans conducted searches on this topic often or very often (though a similar share, 30%, did so rarely or never).

* Wording of question is described in narrative.

** Not every observed difference between demographic groups (e.g., between the youngest adults and those age 60+, or between Asian and White Americans) is statistically significant at the 5% level. The report narrative discusses notable differences that were found to be statistically significant.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

Although it is not apparent from Figure 1G, the survey found that income was related to online research of history topics. While there was not a statistically significant difference between income groups with respect to frequent engagement, the survey detected a difference between income groups in the shares who rarely or never performed online research of history subjects. While only 23% of the highest-income Americans engaged this infrequently, 36% of the lowest-income Americans rarely or never went online to research a history topic.

A quarter of American adults often or very often sought information online about famous figures with a humanities connection (defined as a “philosopher, writer, historian, artist, or musician”), while another 31% did so sometimes. A similar share, 23%, often or very often conducted searches for information about humanities subjects (“art, history, literature, or philosophy”) to gain a deeper understanding, and another 31% engaged in such research sometimes.

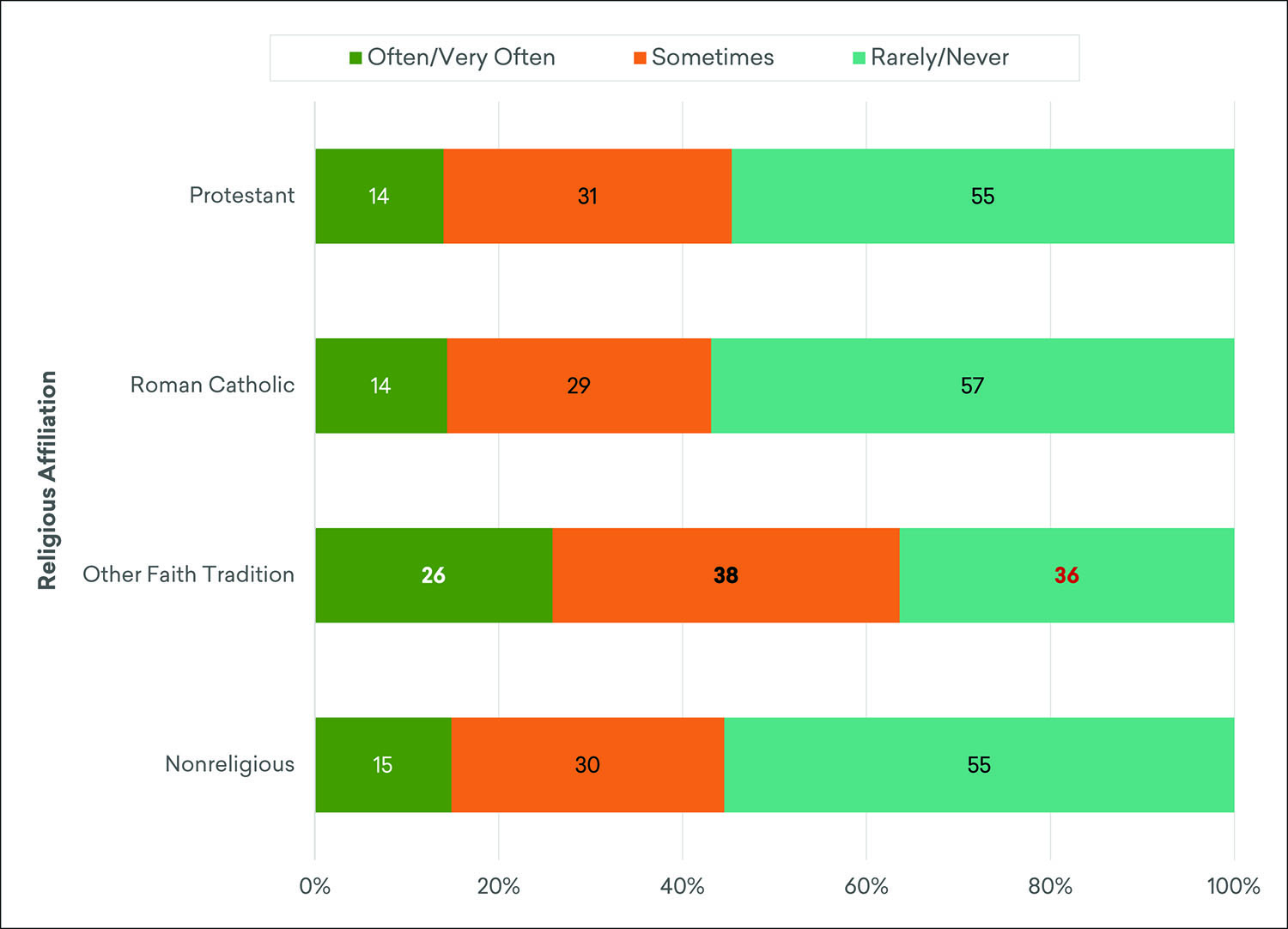

A smaller share of Americans, 15%, often or very often went online in search of information about a religion or culture different from their own. However, members of the two largest Christian faith groups in America, Protestants and Roman Catholics, together with the nonreligious, were statistically less likely than those of other faith traditions to explore religious and cultural differences online (Figure 1H).

* Values in boldface are measurably different (black/white: higher; red: lower) at the 5% level from the share for all adults. Not all differences between faith groups are statistically significant at this level. The report narrative indicates the groups between which statistically significant differences were found.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

Race was also predictive of online research on other religions or cultures, with Whites being less likely than Black and Hispanic Americans to have engaged. Age was also modestly associated with such online searches. Younger Americans were somewhat more likely than older adults to have sought such information. The disparity between the groups was modestly greater in the shares rarely or never seeking such information. Fifty-eight percent of Americans age 60 and above sought such information that infrequently, compared to 47% of those ages 18 to 29.

As was true for most reading-related practices, Americans with at least a college degree were substantially more likely than those with a high school diploma or less to have engaged in every type of online information gathering. Further investigation revealed that, except for research on history topics, humanities majors were more likely than college graduates in general to have frequently conducted humanities-focused research online. For example, 46% of humanities graduates often or very often looked up information about famous humanists, compared to only 30% of all college-educated Americans.

Heading Out for the Humanities

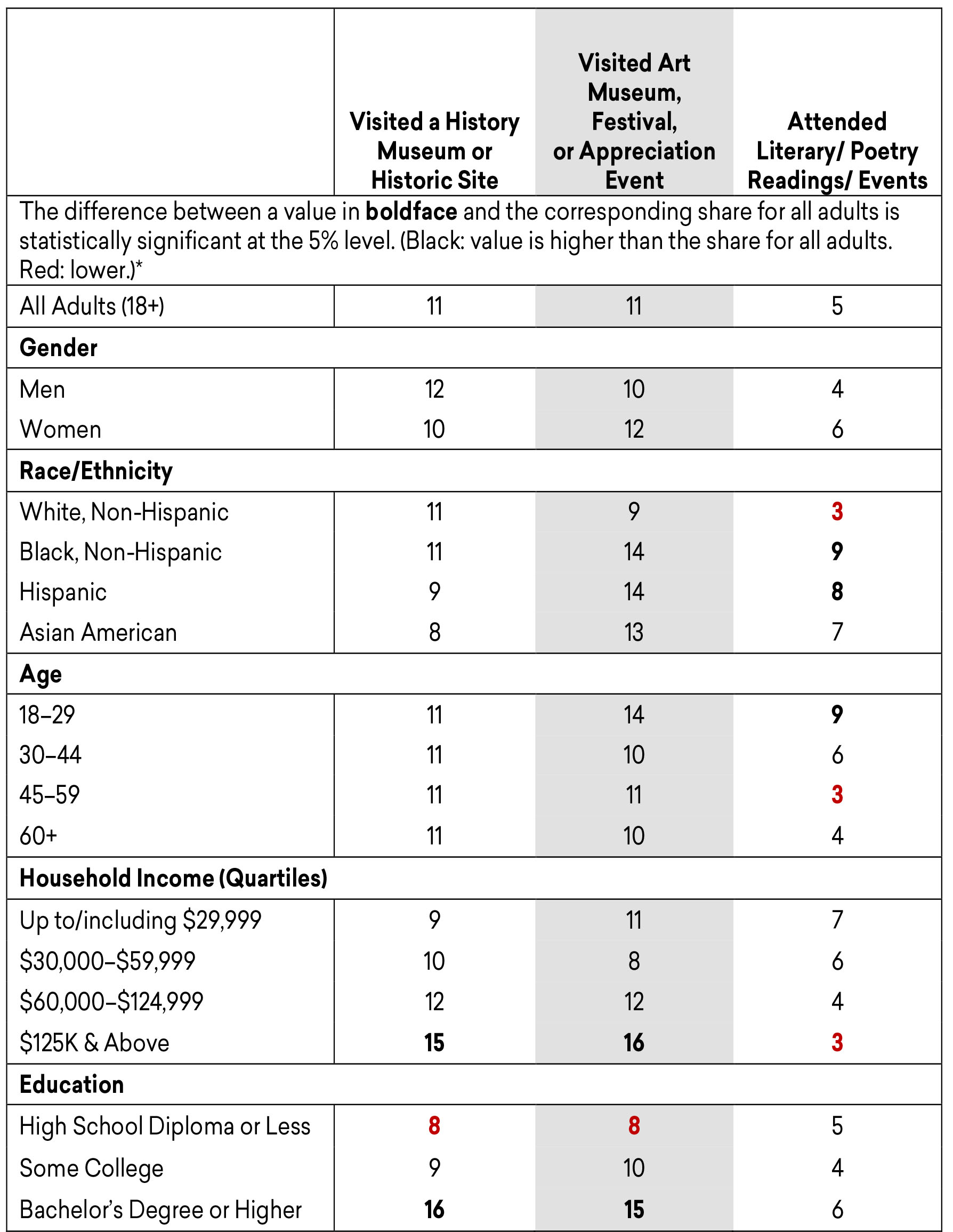

While most of the engagement questions included in the survey asked about activities that can be undertaken in private, the survey also asked about forms of humanities engagement that involve venturing outside one’s home: visits to museums and historic sites, attendance at art festivals and other art appreciation events, and participation in literary and poetry activities.

History- and art-related outings were similar to one another (and most other forms of humanities activity) in that they were more common among those with college degrees (Figure 1J). Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the associated costs, Americans with the highest incomes were more likely to have engaged in these activities often or very often than those in lower-income categories.

* Not every observed difference between demographic groups (e.g., between the youngest adults and those age 60+, or between Asian and White Americans) is statistically significant at the 5% level. The report narrative discusses notable differences that were found to be statistically significant.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

Literary events stood apart from the other types of humanities outings. First, though only a small share of Americans engaged in any of the three types of outings with any regularity, attendance at literary events was even less common. Just 5% of adults attended these events often or very often, while 84% did so rarely or never. Americans with a college degree were more likely than those with a high school education or less to make history- and art-related trips, but education was not found to be predictive of literary event attendance. And though income was related to literary event attendance, Americans in higher income categories were less likely to participate in such outings.

There were also differences among racial/ethnic and age groups with respect to literary event attendance. Hispanics and Black Americans were nearly three times as likely to have frequently attended such events as Whites, and the youngest American adults were more than twice as likely as those 45 and older.

Additional Forms of Engagement

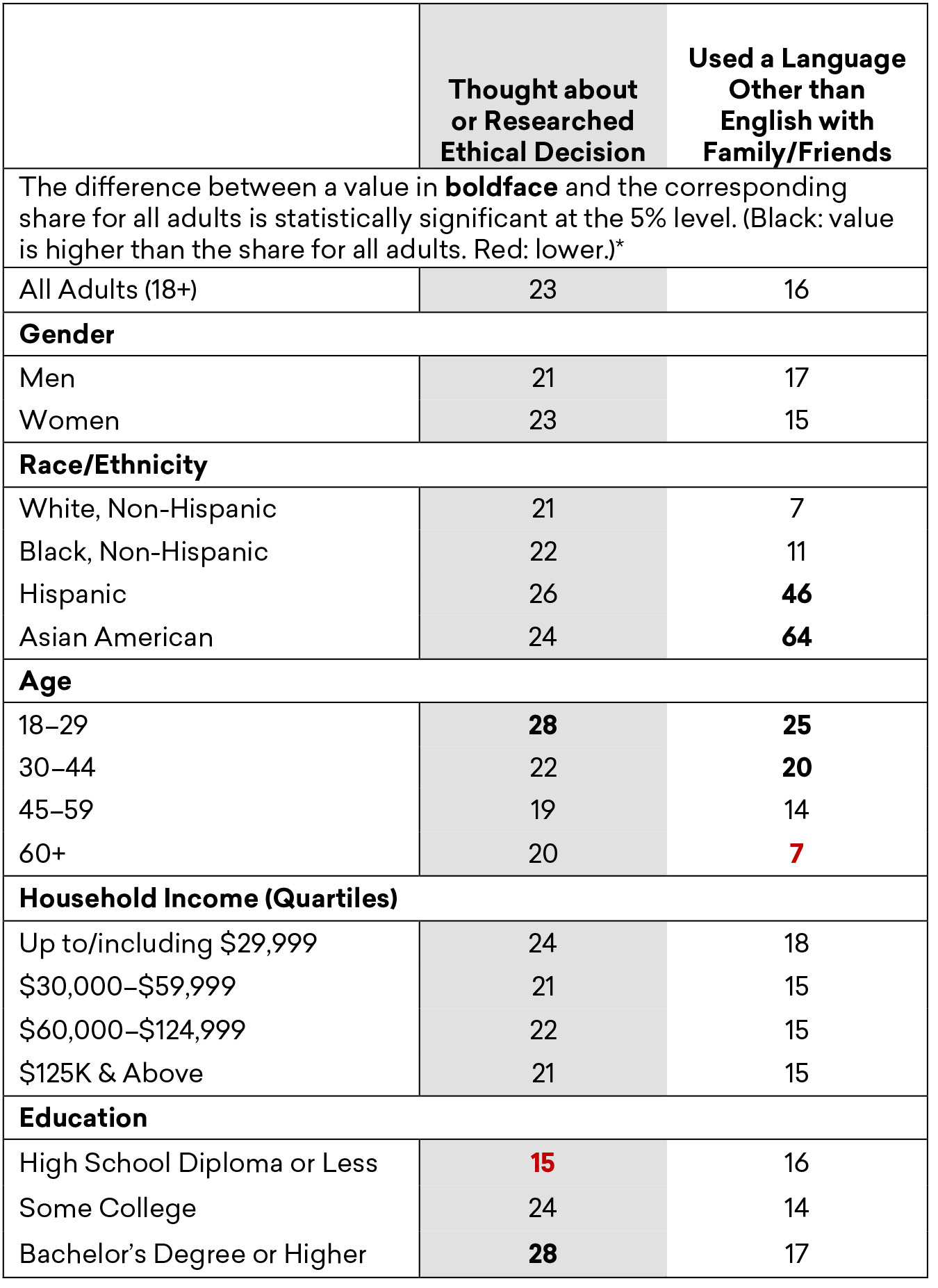

Finally, the survey asked about two other types of connection with the humanities—ethical thinking and use of a language other than English—that do not fit neatly within the other activity groupings explored in the survey.

Twenty-three percent of Americans often or very often thought about or researched the ethical aspects of a choice in their life (and another 31% did so sometimes; Figure 1K). The youngest adults, ages 18 to 29, were somewhat more likely to have engaged ethical questions than older Americans, and Americans with at least a college degree were more likely to have done so than those with a high school diploma or less education. (These findings invite further study of public understandings of the term ethics, as well as perceptions about what it means to engage in thinking on the subject.)

* Not every observed difference between demographic groups (e.g., between the youngest adults and those age 60+, or between Asian and White Americans) is statistically significant at the 5% level. The report narrative discusses notable differences that were found to be statistically significant.

Source: Survey of the Humanities in American Life, 2019.

The final humanistic activity included in the survey was the use of a language other than English with family and friends. (The use of languages at work is discussed in Chapter 4.) The survey found that 16% of Americans often or very often used a language other than English in their personal lives. Seven percent of Americans who identified as “White (Non-Hispanic)” used a language other than English often or very often with family or friends (84% did so rarely or never), and 11% of Black Americans used another language regularly (76% did so rarely or never). A dramatically larger share of Hispanics (46%) and Asian Americans (64%) used a language other than English frequently.

A quarter of Americans ages 18 to 29 used a language other than English with family and friends often or very often, compared to only 7% of Americans age 60 and above. Conversely, 59% of 18-to-29-year-olds rarely or never used a language other than English, while 84% of Americans age 60 or above used a non-English language that infrequently.

____________________

The survey was designed to illuminate not only how Americans “do” the humanities, but also how they feel about them. The next chapter explores Americans’ beliefs about the field and what it contributes to their personal well-being, the nation’s civic life, and the economy. As in this chapter, there will be an exploration of the similarities and differences among demographic groups, with a focus on those who hold strongly positive opinions about the field as well as those with negative views about the humanities.