Principle 12: Encourage Commitments in the Form of Accountable Climate Action Plans

When people, organizations, and governments make concrete commitments through climate action plans, they are more likely to take the promised action. Concrete commitments also help others hold them more accountable and reduce the likelihood of greenwashing.

The challenge being addressed:

Moving past virtue signaling and greenwashing to create, monitor, and hold corporations and governmental entities accountable for effective climate action plans.

The climate science:

The future habitability of Earth for human societies depends on the collective actions humanity takes now. There is rising evidence that this is a decisive decade (2020–2030). Loss of nature must be stopped and deep inequality counteracted. Global emissions of greenhouse gases need to be cut by half in the decade of 2021–2030. This alone requires collective governance of the global commons—all the living and non-living systems on Earth that societies use but that also regulate the state of the planet—for the sake of all people in the future (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2021).

When an individual or entity commits themselves to a plan, the likelihood of taking the planned action increases (Green and Gerber 2019). Peer pressure within a sector increases the adoption of similar commitments among peers. Public accessibility of plans increases accountability.

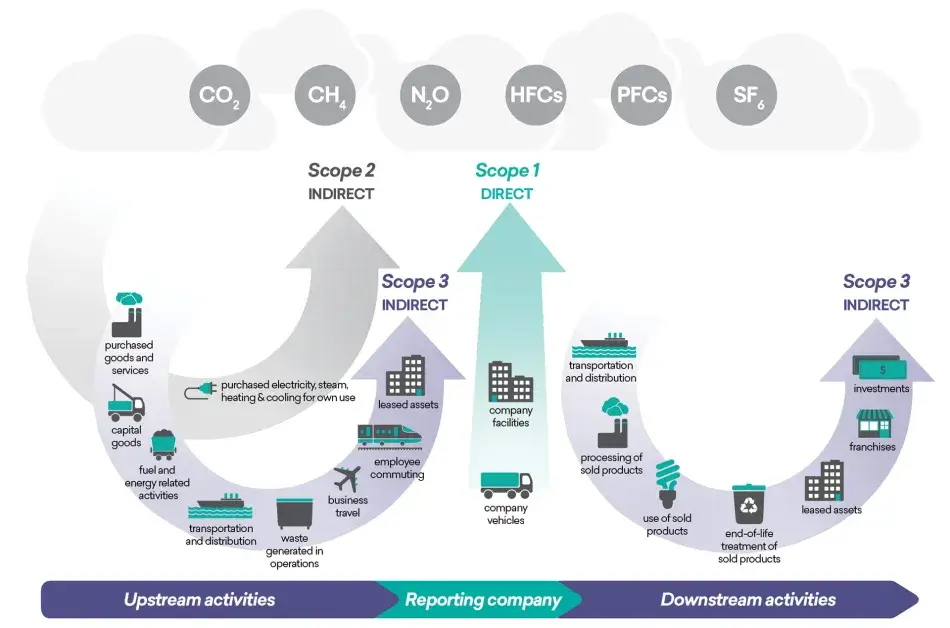

Example 1 (corporate): Greenhouse Gas Protocol

Nonstate actors have an important role to play in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Determining whether a company is meeting its commitment to becoming carbon neutral or negative requires an accurate disclosure of its carbon footprint. “[T]he standard for corporate reporting of greenhouse gases, adopted by governments for regulations, NGOs for accountability and corporations for compliance” (Patchell 2018)—the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHGP)—is conceptualized as “an international accounting tool to assist with understanding, quantifying, and managing greenhouse gas emissions” (Andrew and Cortese 2011). Created by the World Resources Institute in conjunction with the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, the GHGP “provides accounting and reporting standards, sector guidance, calculation tools and trainings for businesses and local and national governments” (World Resources Institute, n.d.). Its “comprehensive, global” frameworks provide sector-adapted accounting and reporting tools to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from corporations and public-sector entities. These tools detail best practices and knowledge that entities can use to inventory their emissions (Greenhouse Gas Protocol, n.d.-b). “The GHG Protocol,” notes social scientist Jerry Patchell (2018), “asks companies to assess their responsibility for GHG emissions from their internal operations, energy bought from external sources and used internally (principally electricity), and the emissions their products incur upstream and downstream in the value chain. These responsibilities are termed scopes 1, 2 and 3 respectively.” “Scope 1 refers to direct emissions from a company’s own activities, scope 2 refers to emissions from the production of purchased energy, and scope 3 refers to emissions from up- and downstream activities along the value chain” (Klaaßen and Stoll 2021). Scope 3 emissions are substantial (Hertwich and Wood 2018).

Overview of GHG Protocol scopes and emissions across the value chain

Source: World Resources Institute, n.d.

Effectiveness:

According to the GHGP, more than nine out of ten Fortune 500 companies reporting to the CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project), “a not-for-profit charity that runs the global disclosure system for investors, companies, cities, states and regions” (CDP, n.d.), use the GHG Protocol (Greenhouse Gas Protocol, n.d.-a). “The CDP,” according to business professors Jane Andrew and Corinne L. Cortese, “has increased the amount of carbon related corporate information in the public domain. In fact, its size and scope is impressive[,] holding out the promise of widespread climate change related allocation decisions, disciplining the market towards sustainable futures and carbon sensitivities” (Andrew and Cortese 2011).

Political scientist Jessica F. Green argues that these “two NGOs were successful rule-makers because they were able meet a demand for three benefits to potential users of the standard: reduced transaction costs, first-mover advantage, and an opportunity to burnish their reputation as environmental leaders” (Green 2010). However, others caution that “Only if private companies receive a clear political signal that stringent mandatory GHG emission controls and a global market-based instrument are at least likely to be adopted will they put substantial efforts into the accurate measurement and management of their GHGs” (Hickmann 2017). Furthermore, “Current carbon accounting and reporting practices remain unsystematic and not comparable, particularly for emissions along the value chain (so-called scope 3)” (Klaaßen and Stoll 2021).

Example 2 (municipal): Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy

The European Commission launched the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy (GCoM) in 2008 to support European Union locales in mitigating climate change. GCoM is “the largest international initiative dedicated to promoting climate action at a city level, covering globally over 10 000 cities and almost half the population of the European Union (EU) by end of March 2020” (Kona et al. 2021).

Effectiveness:

A study of the emissions reports from the cities in the Covenant of Mayors indicates that “monitoring signatories are on track to reach their commitment” (Kona et al. 2021).

Example 3 (non-profit): American College and University Presidents’ Climate Commitment

Organized by the United Nations to create in-sector social pressure and accountability, the American College and University Presidents’ Climate Commitment (ACUPCC) is designed “to promote the research, education, and community engagement efforts needed to create a sustainable society, and to eliminate net greenhouse gas emissions from specified sources in their own campus operations” (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, n.d.).

Examples:

University of Buffalo Climate Action Plan; and University of Pennsylvania Sustainability.

Effectiveness:

To date, nearly seven hundred educational institutions have signed the pledge, making their climate action plans and progress reports publicly accessible, pending website updates, via the ACUPCC Reporting System.

Example 4 (health care): Health Care Sector Climate Pledge

On Earth Day 2022, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in partnership with the White House urged health care stakeholders to take the Health Care Sector Climate Pledge, which promises,

We voluntarily pledge to: 1. At minimum, reduce organizational emissions by 50% by 2030 (from a baseline no earlier than 2008) and achieve net-zero by 2050, publicly accounting for progress on this goal every year. a) Share publicly our strategies for reducing on-site emissions (where relevant addressing sources related to on-site energy usage, waste anesthetic gases, vehicle fleets and refrigerants). 2. Designate an executive-level lead for our work on reducing emissions by 2023 and conduct an inventory of Scope 3 (supply chain) emissions by the end of 2024. 3. Develop and release a climate resilience plan for continuous operations by the end of 2023, anticipating the needs of groups in our community that experience disproportionate risk of climate-related harm (U.S. Health and Human Services, n.d.).

More than six hundred hospitals have signed onto the pledge (White House 2022). Organizations that have signed the pledge were publicly recognized. (The list of signatories is available here.)

Example 5 (accountability): Global Fossil Fuel Divestment Commitments Database

Source: DivestmentDatabase.org/Stand.earth.

As The New York Times noted, “Two environmental nonprofit groups, Stand.earth and 350.org, started a website to keep track of divestment pledges from universities, banks, companies and even Queen Elizabeth II. So far, the list includes more than 1,500 institutions and businesses worth some $40 trillion” (Andreoni 2022).

The need:

Increase the number of organizations and individuals committed to plans that address and reduce climate change, timelines that meet the need, and forms of disclosure that ease monitoring and maximize accountability of the plans and their promulgators.

Example 6: Tying personal to institutional accountability

A resolution of the Executive Committee of the Faculty Senate at the University of Pennsylvania asked faculty members to sign a pledge agreeing not only to take these individual actions:

- to support and encourage relevant teaching and research initiatives in our respective schools and departments, and centers and initiatives;

- to reduce our personal carbon footprints with respect to our air travel (including the purchase of reliable offsets when such travel is necessary) and our energy use at work, at home, and in transportation between work and home;

- to examine our personal retirement investment portfolios in order to align them as closely as possible with our values favoring a radical reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and new business solutions to the climate challenge;

but at the same time to make these efforts to create institutional change:

- to encourage our Schools, departments, Centers, and other administrative units to become active in the Green Office Program, including certification for reducing energy use, greening supply purchases, and adopting green catering options;

- to work within our academic and professional societies to find pathways to a less carbon-intensive future—in particular to create alternatives to conference travel.

A copy of the climate pledge is available here.

A video produced by the Faculty Senate to encourage members of the Penn community to sign the pledge is available here.