Contributing to Development and Application of Ethical Norms and Scientific Guidelines

Scientific research has often raised ethical questions and carries ethical obligations. Norms and guidelines, when developed for a global science effort, can have widespread implications. For the perspectives of U.S. scientists to be represented in the development of global ethical frameworks, it is important for the United States to actively participate in and promote international forums engaged in developing ethical guidelines for research.

The ethical questions that confront scientists are becoming increasingly complicated as technology advances. Developments and tools that have raised questions about ethical guidelines include rapid genetic sequencing and editing capabilities, the establishment of large biobanks, the use of comprehensive data sets that threaten personal anonymity, biases in machine learning technologies including facial recognition and predictive analytics, emerging neurotechnologies such as brain implants, and fast-moving cyber security research.128 Ensuring ethical care of human subjects and biological samples such as human cells and tissue has proven especially difficult with the development of new technologies.

As discoveries and technological capacities increase, ethical questions are becoming more complex, especially when accounting for the range of ethical and cultural norms within the international community and considering shifting societal contexts, such as a history of colonialism or xenophobia. Collaborators must also develop norms for the ethical scientific conduct within partnerships, such as protocols for sample and data collection, appropriate attribution and assignment of credit, and ownership of samples and intellectual property.

The international community of scientists has an opportunity and a responsibility, in concert with individual nations’ interests and guidelines, to develop and apply ethical norms as a globally connected community.129 This approach has found some success in the past, for example through the Asilomar Conference on Recombinant DNA, which developed guidelines for ethical research in DNA manipulation (see Asilomar Conference on Recombinant DNA: Promoting Ethical and Safe Research).130 The Asilomar Conference is also an important example of how the codevelopment of ethical norms and guidelines promoted international peace and security, as the United States and other countries adopted the safety guidelines and recommendations produced as a way to protect their populations while still furthering the science. Nascent efforts for international governance of emerging technologies like AI hope to achieve a similar goal.131

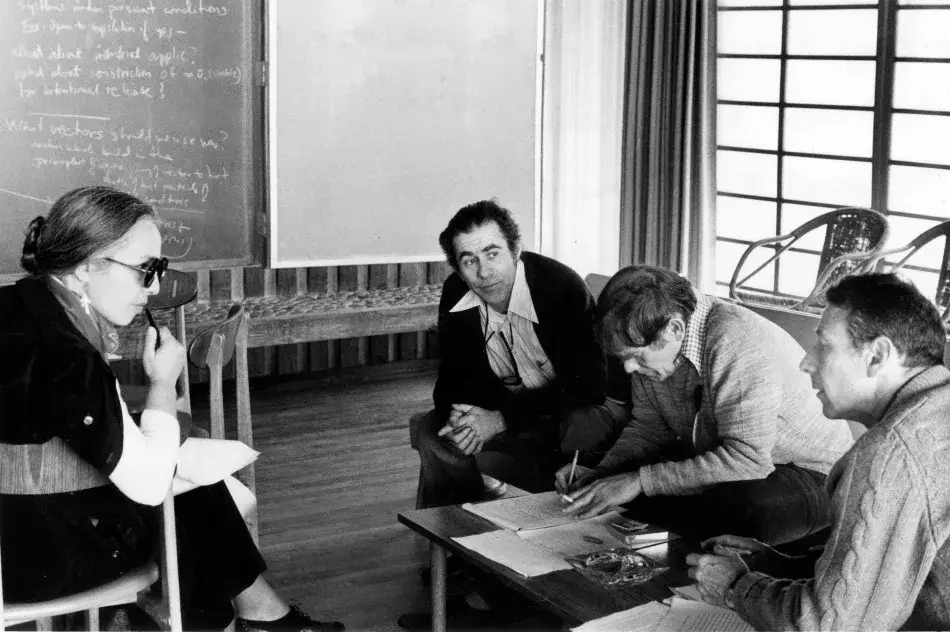

Asilomar Conference on Recombinant DNA: Promoting Ethical and Safe Research

The 1975 International Congress on Recombinant DNA Molecules, commonly referred to as the Asilomar Conference on Recombinant DNA after its host location, gathered molecular biologists from around the world to discuss potential risks of research that involved manipulation of DNA. It is an important example of U.S. leadership in the establishment of ethical guidelines for biological research.

Maxine Singer, Norton Zinder, Sydney Brenner, and Paul Berg (left to right) at the Asilomar Conference on Recombinant DNA, 1975. Image courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.