Introduction

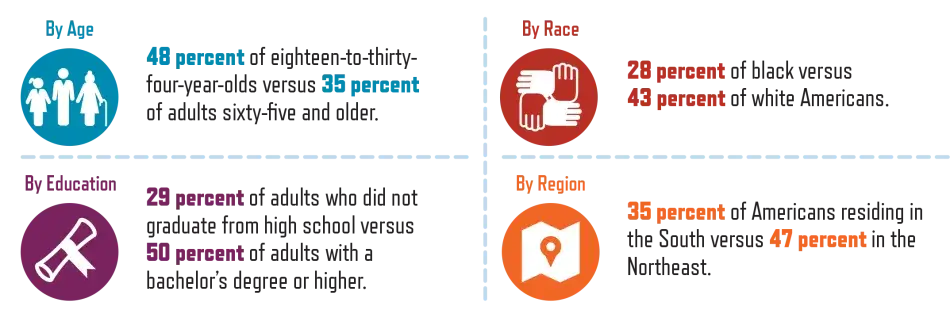

In February 2018, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences released the first report from its Public Face of Science Initiative. Titled Perceptions of Science in America (see Takeaways from Perceptions of Science in America for its primary conclusions), the report presents data showing that confidence in scientific leaders has remained generally stable over the last thirty years, but that attitudes toward science vary based on age, race, educational attainment, region, political ideology, and other factors. Taken together, these data support the notion of a heterogeneous public whose perceptions depend on context and values.

In addition to the inherent socioeconomic, racial, and cultural diversity of the public, attitudes toward science are also influenced by an individual’s experiences with science and exposure to scientific information throughout his or her lifetime. One objective of this report is to improve understanding and awareness of the range of participants, approaches, and outcomes that form this complex landscape of science communication and engagement among communities interested in participating in or supporting the practice. The report highlights key contexts for engagement with science and provides an overview of approaches to science communication and engagement. These considerations are particularly important because the design and execution of these activities directly affect their outcomes and impact. A second objective of this report is to illustrate how science communication and engagement can be designed to achieve specific societal impacts.

A Heterogenous Public

Percentage of U.S. Adults with a “Great Deal” of Confidence in the Leaders of the Scientific Community:

SOURCE: NORC at the University of Chicago, General Social Survey (2016). Race was self-identified through the question, “What race do you consider yourself?” Race categories are as reported by NORC. For full demographic data, see American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Perceptions of Science in America (Cambridge, Mass.: American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2018).

This report is primarily concerned with deliberate efforts to reach general audiences, rather than targeted groups such as policy-makers or K–12 students and educators. Section 1 of this report presents an overview of a broad conceptual framework for approaching science communication and engagement, with an emphasis on the participants, their motivations, and potential outcomes. It also describes additional resources for science engagement. Section 2 provides an overview of common ways people engage with and communicate science, including the types of venues and activities, who participates in them, and their motivations for participating. Section 3 discusses designing science communication and engagement activities for specific impacts, such as broadening participation in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

Individual conversations, news reports, and entertainment also present important opportunities to learn about and interact with scientific content. The special section on Science in Everyday Life highlights data from a recent Pew Research Center report that provide insight into trust in science news and experiences with other information sources.

There are diverse and expanding ways for people to encounter science and an increasing effort to evaluate the outcomes of these encounters. However, the cumulative impacts of these experiences on a person’s attitudes toward science are not well understood. Continued and expanded support for interdisciplinary collaborations among scholars, professional practitioners, scientists, and communicators will be necessary to achieve a greater understanding of how these experiences contribute to long-term changes in attitudes and behaviors toward science. An improved awareness of the heterogeneous ways people experience science, and the potential outcomes of these experiences, will ultimately enhance efforts that seek to shape the public face of science.

The Link between Scientific Research and Public Engagement

Research agencies in the United States have recognized the importance of communication and engagement in the context of federally funded scientific research. The National Science Foundation (NSF) grant merit review requirements codify this relationship through a “broader impacts” (BI) criterion that “encompasses the potential to benefit society and contribute to the achievement of specific, desired societal outcomes.”1 BI goals may include “increased public scientific literacy and public engagement with science and technology.”2 Despite the inclusion of these requirements since 1997, a recent report from the National Alliance of Broader Impacts (NABI) found that “much work remains to clarify BI criterion and how to effectively address it.”3 Several of the recommendations from this NABI report are applicable to the fields of science communication and engagement, such as increasing the capacity of scientists to fulfill BI requirements and providing greater institutional and professional support to expert practitioners. To this end, Encountering Science in America conveys the fundamental concepts that scientists and institutions should consider when developing and conducting BI activities.

Defining the Practice

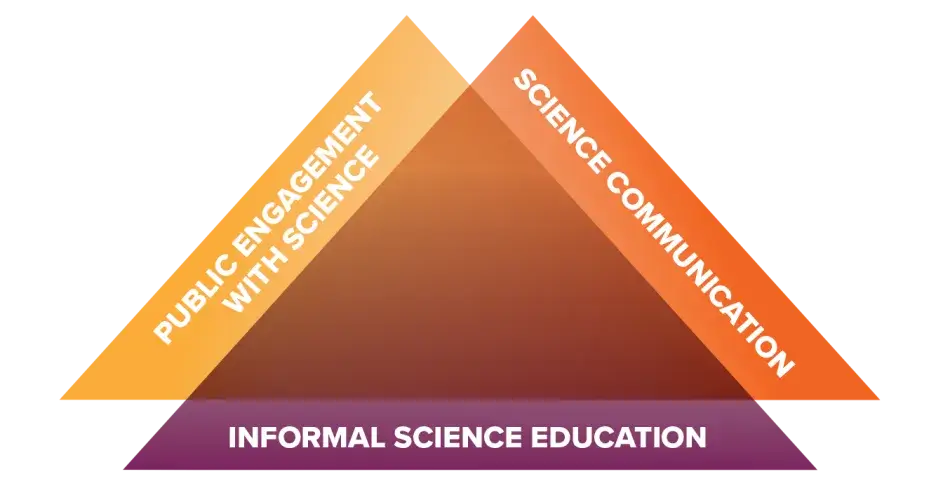

While science communication, public engagement, and informal science education have much in common, they can be viewed as distinct fields that share similar goals and practices.4 Each of these fields may seek to influence the accuracy and accessibility of scientific information, the quality of science-based experiences, and opportunities for direct engagement with content experts. However, informal science education focuses on outcomes associated with learning and public engagement activities whose designs and settings take audiences’ interests, prior learning, and culture (or identity) into account. The distinction between science communication, engagement, and education is particularly evident among the practitioners and those who study the practices. The science of science communication—a specialized subfield that studies “how science can best be communicated in different social settings” and the effectiveness of these methods—is one specific example.5 The rise of this interdisciplinary research has helped advance the practice of science communication and engagement.

Public Engagement with Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) defines “public engagement with science” as “intentional, meaningful interactions that provide opportunities for mutual learning between scientists and members of the public.”6

Science Communication

A National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) report on communicating science effectively defines science communication as “the exchange of information and viewpoints about science to achieve a goal or objective such as fostering greater understanding of science and scientific methods or gaining greater insight into diverse public views and concerns about the science related to a contentious issue.”7

Informal Science Education

The Center for Advancement of Informal Science Education (CAISE) describes the field of informal science education as pursuing opportunities for “lifelong learning in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) that takes place across a multitude of designed settings and experiences outside of the formal classroom.”8