To celebrate the arts, artists, and the work of the Academy’s Commission on the Arts, Stephen Colbert, host of “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert,” talked with Commission Cochairs John Lithgow, Deborah Rutter, and Natasha Trethewey. The program included poetry, music, and a discussion of the recommendations developed by the Commission to elevate the arts, support artists, and promote arts education in America. The event also introduced Mixtape, an online collection of arts experiences that features members of the Commission and members of the Academy. An edited version of the presentations, conversation, and Q&A session follows.

2101st Stated Meeting | October 27, 2021 | Virtual Event

Natasha D. Trethewey is Board of Trustees Professor of English in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences at Northwestern University. She served two terms as the 19th Poet Laureate of the United States (2012–2014). She was elected a Fellow of the American Academy in 2013, is a member of the Academy’s Board of Directors, and is a cochair of the Academy’s Commission on the Arts.

Thank you for joining us in this celebration of the Commission’s work. As invocation, I am going to read a poem that speaks both to the necessity for and the resilience of the arts. It is a poem by an Academy member, the late Lucille Clifton, entitled “won’t you celebrate with me.”

won’t you celebrate with me

what i have shaped into

a kind of life? i had no model.

born in Babylon

both nonwhite and woman

what did i see to be except myself?

i made it up

here on this bridge between

starshine and clay,

my one hand holding tight

my other hand; come celebrate

with me that everyday

something has tried to kill me

and has failed.

Lucille Clifton, “won’t you celebrate with me,” from Collected Poems of Lucille Clifton. Copyright © 1991 by Lucille Clifton. Reprinted with permission of BOA Editions Ltd., www.boaeditions.org.

David W. Oxtoby is President of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy in 2012.

Thank you, Natasha, for that beautiful beginning. And thank you all for joining our program “New Horizons: Elevating the Arts in American Life,” a celebration of the work of the Academy’s Commission on the Arts. As president of the American Academy, it is my distinct pleasure to officially call to order the 2101st Stated Meeting of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

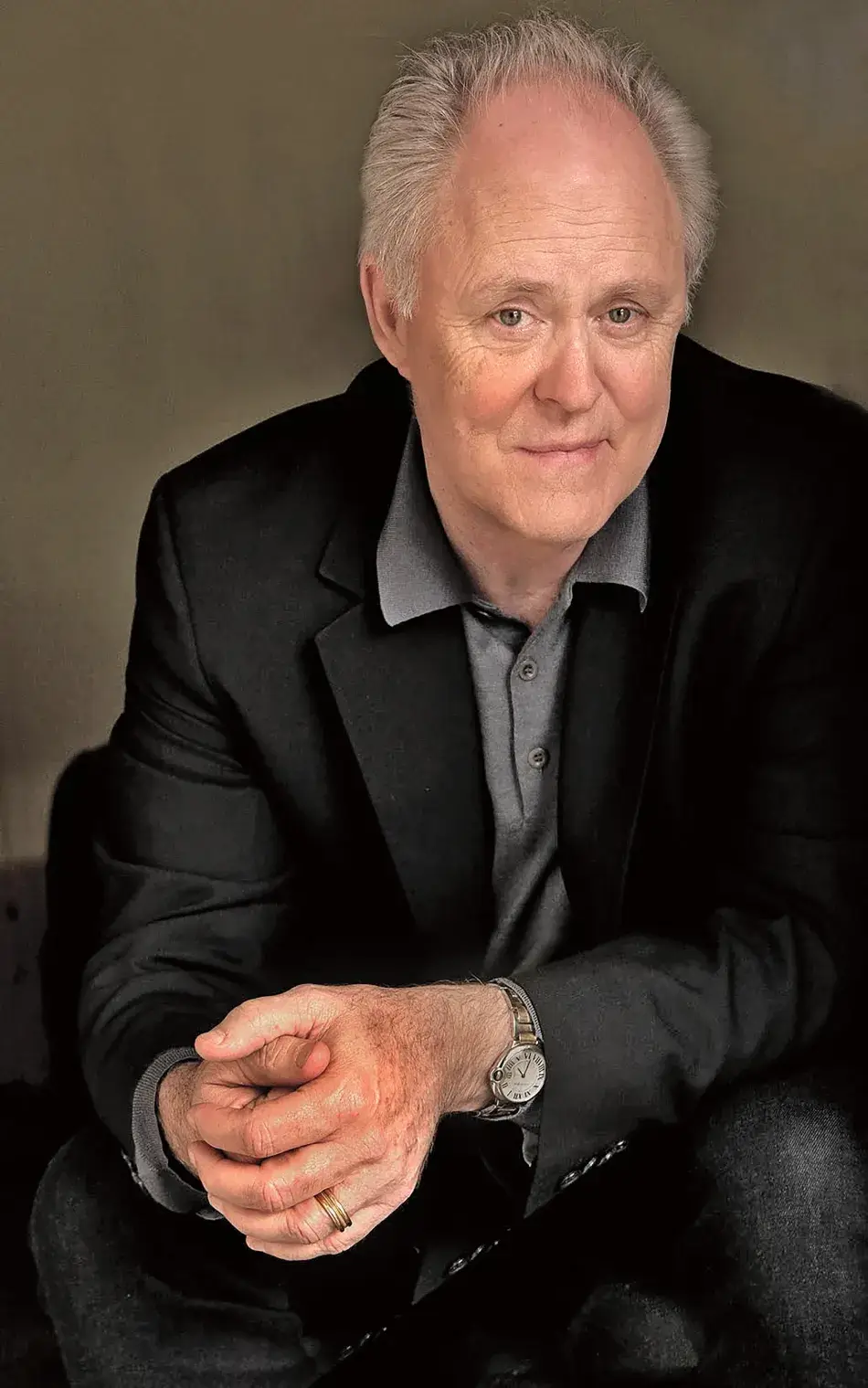

Since our founding in 1780, the American Academy has worked to address the most critical issues facing the nation, regularly assembling for Stated Meetings to have important and timely conversations. In recent years, that work has included cross-disciplinary projects and commissions to address science communication, democratic citizenship, undergraduate education, and now the arts. Today is the day to honor the hard work of our Commission on the Arts and to share the results of their three years of effort to bring greater recognition and resources to the arts and to artists. As you will see and hear today, the Commission’s final reports and projects respond directly to unique challenges facing the arts in our current world. The incredible work of the Commission is reflective of the diverse perspectives and experiences of its members and especially of its three cochairs, who are here today. You have already heard from one cochair, Natasha Trethewey, who opened the program with that powerful poem by Academy member Lucille Clifton. Natasha is the Board of Trustees Professor of English at Northwestern University and a Pulitzer Prize – winning poet. She also served two terms as the nation’s Poet Laureate (from 2012–2014). She is the author and editor of many volumes of poetry, and while serving as Poet Laureate, she developed the PBS NewsHour series, “Where Poetry Lives.” Natasha was elected to the American Academy in 2013 and is a member of our Board of Directors. Our second cochair is Deborah Rutter, who has served as president of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts since 2014. The Kennedy Center is the world’s busiest performing arts center, presenting theater, contemporary dance, ballet, vocal music, chamber music, hip-hop, comedy, international arts, jazz, classical music, and opera. Her tenure has focused on supporting arts education and creating opportunities for encounters between artists and the public. Deborah was previously the president of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association. She was elected to the Academy in 2018 and is a member of our Board of Directors. And our third cochair is actor and author John Lithgow. John is a prolific artist and arts advocate, whose work spans many mediums. He has written children’s books, recorded albums, and performed on the stage, screen, and television. Through his genre-spanning career, John has been nominated for two Academy Awards and received two Tonys, six Emmys, and two Golden Globes. John was elected to the American Academy in 2010 and has served on our Board of Directors and on an earlier Academy Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences. It is my pleasure to turn things over to John, who will elaborate on the work of the Commission and the crisis facing the arts today.

John A. Lithgow is an actor and author. He has appeared in over twenty productions on Broadway, including The Changing Room and the musical adaptation of Sweet Smell of Success; he won Tony Awards for both. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy in 2010 and has served as a member of the Academy’s Board of Directors and as a member of the Academy’s Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences. He is currently a cochair of the Academy’s Commission on the Arts.

In 1780, John Adams had his eye on the future and his mind on the arts. Adams, the cofounder of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, stated that he must “study politics and war so that [his grandchildren] could study painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry, and porcelain.” This florid proclamation from a founding father is hard evidence that from the very beginning, the arts have been at the heart of the great American experiment. In the estimation of John Adams, our highest aspirations as a nation even included porcelain.

Today marks the culmination of a three-year American Academy of Arts and Sciences’ Commission on the Arts. It is the most recent among scores of Academy research projects over the years, but despite the optimistic timeline of John Adams, it is the first devoted exclusively to the arts. Our forty-plus commissioners include the heads of arts institutions, foundations, and philanthropies but also artists of every stripe – surely the most colorful and diverse group the Academy has ever convened.

The Commission may have been a long time coming, but it could not have come at a more crucial time. Indeed, over the course of its three-year life, the urgency of its mission has shot up, and the reasons are obvious. When we first met three years ago, we set out to survey the state of the arts in America today, an assignment equal parts celebratory and exploratory. We were eager to highlight the exuberance and variety of creative life in all fifty states of the nation, but we aspired to far more than cheery boosterism. We were equally intent on addressing issues of need, neglect, and inequality across the artistic landscape. Our commissioners brought extraordinary breadth and depth to these intractable problems. They have spent their careers grappling with them, but in joining forces, they attacked these challenges with a renewed sense of can-do optimism.

Our first in-person sessions were downright festive, but then halfway through our journey everything changed. The curtain descended on our festivities. COVID struck, the American economy tanked, and George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis, triggering a nationwide outcry for racial justice. These three concurrent crises throttled every American community and exposed gaping fault lines in our social contract. For artists, the impact was catastrophic. A life in the arts can be hard at the best of times, but 2020 was a year of desperation and panic. For the most part, the arts rely on crowds of people gathered in a shared experience. For artists, a world without an audience is a garden without sunlight: it desiccates and dies.

But our Commission soldiered on with grim determination. We met in small groups on Zoom and took on a pressing, new question: What can we do to help shore up the livelihood of the American artist and bring the arts back to life? We took a hard look at all our pre-pandemic goals and reconfigured them to address the immediate firestorm. The two reports we produced reflect this midstream pivot. They focus on challenges that existed in the American arts community long before the COVID crisis struck, but the crisis itself has rendered these challenges existential. The titles of the two reports announce their urgent themes. The first is entitled Art for Life’s Sake: The Case for Arts Education, and the second is Art Is Work: Policies to Support Creative Workers.

With this two-pronged approach, we have worked to address the deprivations endured by two vast American populations in a time of crisis: our young people who have lost a precious year of education and social development, and our arts workers whose professional lives have been ravaged. These are dark themes to be sure, but in all our deliberations, we have been driven by the fervent belief in the power of art to energize, heal, educate, provoke, unify, and bring joy to human beings. In our view, art is not simply a luxury; it is essential to civil society and to the strength of the human spirit.

John Adams and the rest of our founding fathers agreed. History tells us that Thomas Jefferson in drafting the Declaration of Independence reworked John Locke’s triad of life, liberty, and property. For property, Jefferson substituted the pursuit of happiness. That remains the most enduring phrase in that founding document. Jefferson, an architect and violinist as well as a statesman, surely had art on his mind when he penned it. For an artist, self-expression is the pursuit of happiness, but the rest of us pursue happiness too. Every time we listen to music, read a story, recite a poem, sit in an audience, or linger on a visual image, art exists in all our private and public spaces often when we barely notice that it is there.

We on the Arts Commission of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences declare that now more than ever the arts must not be neglected and must not be taken for granted. For our collective good, for the good of our nation, and for our right to the pursuit of happiness, the arts must be supported.

OXTOBY: Thank you, John. The American Academy is proud to realize the vision of our founders by addressing the arts head on with this commission. Under the leadership of John, Natasha, and Deborah, the Commission on the Arts has done incredible work, nimbly responding to the tumult of the last few years. The two reports produced by the Commission reflect the work of not just the cochairs, but over forty commissioners – artists, scholars, activists, and leaders of institutions and philanthropies – as well as Academy staff and participants from the wider arts world, who embraced our mission, joining in conversations, sharing their work, and spreading the word. Many of you are in the audience today, and I want to thank you for offering your time and talents to this vital work. We are also grateful for the support of the Barr Foundation, Ford Foundation, Getty Foundation, John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Kresge Foundation, and Roger and Victoria Sant, as well as the partnership with the Public Broadcasting Service and the Kennedy Center. I would now like to turn to Deborah, who will introduce our next segment.

Deborah F. Rutter is President of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. She was elected a Fellow of the American Academy in 2018, is a member of the Academy’s Board of Directors, and is a cochair of the Academy’s Commission on the Arts.

Thank you, David. What a joy it is for all of us to be together, even in this virtual way. My two amazing, talented, fantastic cochairs are both artists, and you have already had a little bit of that experience with them. What a beautiful way for us to start this conversation today. My contribution is secondhand: it is a short, but fun clip from the recent PBS broadcast of the fiftieth anniversary celebration concert at the Kennedy Center, perhaps the first of its scale to happen in our country, and certainly in our nation’s capital. The clip features the amazing jazz vocalist Dianne Reeves and bassist Christian McBride, with a surprise collaborator, Ray Chen, together with the National Symphony Orchestra conducted by Thomas Wilkins. And stay tuned for some extra special surprises of tap and some swing dancing. Here is Duke Ellington’s “It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing).”

[Event participants watch a clip of the Kennedy Center concert.]

OXTOBY: That was wonderful. Thank you, Deborah. The motivating force for our Commission’s exploration of policy, law, economics, and education was always the power of the arts. The piece you shared is such a vivid illustration of that power. We are grateful to the Kennedy Center for providing the clip. And now let us turn to a conversation between our three cochairs and Stephen Colbert, arts advocate and host of “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert” on CBS.

LITHGOW: We three cochairs of the Arts Commission are honored and delighted that Stephen Colbert has agreed to join us to discuss our two reports and the life of the Commission. Stephen, welcome to our team, and thanks so much for having a conversation with us.

Stephen Colbert is the host of the Emmy and Peabody Award–winning show “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert.”

John, I am very happy to be here, and it is so nice to see you again. Deborah and Natasha, very nice to meet you. My first question to all of you is about the Commission and its goals. The Commission has just released a report that makes the case for the value of arts in our education and the value of arts generally in our society. I am curious how you each first encountered art in your own education.

LITHGOW: I was a public school kid, and not just one public school. I grew up in a theater family. I went to eight different public schools, but in two key years of my life, perhaps key years in everybody’s life, during the ninth and tenth grades, I was lucky enough to be in Akron, Ohio, when their school system believed deeply in the importance of the arts in education. Someone on their school board had the bright idea that students interested in the arts should begin their day with two full periods of art, whether it was music or studio art. At that point in my life, I wanted to be a painter or a printmaker; acting was the last thing I wanted to do. And as a result, I could not wait to get to school every day. That is the thing about enlivening the school experience for kids, making them much more eager to stay in and complete school. Sports has very much that effect, and the arts certainly had that effect on me. My two favorite teachers in public school were Mrs. Thomas in ninth grade and Miss Robinson in tenth grade. Of course, I did not become a painter; everybody knows that. I became an actor.

COLBERT: I have one of your drawings hanging proudly on my office wall, John.

LITHGOW: Well, every chance I get, I draw a picture of Stephen Colbert!

COLBERT: Natasha, how did you first encounter the arts in your education?

TRETHEWEY: My experience is actually very similar to John’s. I started elementary school in Atlanta, in a place that gave us two periods of art first thing in the morning: art class and then music class. I love thinking that that is how we started the day when we were probably at our sharpest and most eager to be there. And it got us going for everything else we had to do for the rest of the day. By the time I was in third grade, we were writing and reading poetry, and that was a transformative experience for me because my teacher and my librarian at the school bound my first volume of poems and put them in the school library. I felt seen as a poet even then, and later, of course, I became one.

COLBERT: Deborah, where did you first encounter the arts as a child?

RUTTER: Well, I think we have a theme here, and I promise you we did not plan this. I come from a musical family, and I started playing piano as a very young child. But it was in the third grade in elementary school, when the teacher opened the cabinet and asked, “What instrument will you play?” that I can point to as a significant moment. It is the same story as John’s and Natasha’s. I chose the violin, and that choice has determined the rest of my life.

COLBERT: That moment? You can literally point to that moment?

RUTTER: Yes, I absolutely point to that moment all the time. I play the piano now for fun, but it is that moment, it is the exploration of the way you feel and the collaboration and the intense discipline of being a musician, that has driven every single important decision of my life.

COLBERT: What was the first piece of art of any kind that moved you when you think back to your childhood? I’ll go first. My mother had a beautiful collection of art books when I was a child, the sort with rice paper in between the prints. From a very young age, without being pointed toward it, I was completely enraptured by Starry Night by van Gogh, and I would return to it over and over again. When I think of my earliest memory of being moved by a piece of art, it is that painting. Do you have a first memory like that?

LITHGOW: My mother saved drawings from when I was four or five years old. I always drew, and I always loved color and line. But when I was thirteen, I would say that aha moment for me was a visit to Washington, D.C., to stay a couple of days with an aunt and uncle; my uncle worked in government. Knowing my interest in art, they dropped me off at the National Gallery, where I spent two of my three days of my visit with my aunt and uncle. Thinking about it now, they were probably trying to get rid of me! I was simply drunk on the history of art. It was extraordinary, and I have been a museum fanatic ever since. Every time I visit a new city, which I do often because of my crazy career, the art museum is always the first place I go.

COLBERT: John, you could have a series of specials in which you recreate that experience in the National Gallery.

LITHGOW: Single malt whiskey would be an important prop for that series.

COLBERT: Natasha, was there a poem when you were a child that moved you?

TRETHEWEY: As you asked that question, I was thinking of two things. My father was a poet, and so from a very early age, I can remember listening to my father recite poetry – from the Lyrical Ballads by Wordsworth and the poems of Yeats and Robert Frost – and then also hearing him as he worked on his own poems. But the other thing I was thinking about was my grandmother, who was a drapery seamstress. We don’t always think of crafts like that as art. But my grandmother was very invested in making beauty, and at one point, she grabbed bolts of fabric that she had that were printed with various scenes from nature, and she decided to make paintings. My grandmother was a working-class woman and would make the art in her home. She took big bolts of cloth, framed them with bric-a-brac and little decorations, and hung them on the walls of this long hallway, transforming it into an art gallery. One of my earliest poems is about the need to make art, and that memory of my grandmother stays with me.

COLBERT: Deborah, what about you? Beyond that moment with the violin or maybe even perhaps that is the moment, do you recall when the arts called to you in an interesting way?

RUTTER: I have two stories: one good and one bad, but therefore directional. The bad one was a school play. It was a Charlie Brown play because we were in elementary school, and I was cast as Lucy. No comment allowed, Mr. Lithgow! I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t remember the lines. I was terrified, and I will never do anything like that ever again. But what it made me realize is how much I loved playing in an orchestra. I have a very strong memory from that same period of performing “L’Arlésienne Suite” by Bizet, a beautiful work, that was arranged for a school orchestra. It is the physical experience as well as the aural experience that I recall so well. It goes to these experiences that you have at a very young age and how that really sets a course for you – and that is what arts education is all about. Whether you become an arts administrator like me or an artist like my two colleagues, that experience at a very young age is so transformative about how you think, how you feel, and what you do with the rest of your life.

COLBERT: That transformative feeling of being part of the orchestra – I had a similar experience when I was a child. I was in the choir singing Mozart’s “Mass,” and I had the feeling almost as if I was levitating as we all found the harmony and the rhythm. I realized it was a very special moment that could only be created with intention for those of us seeking the same creative moment.

The next question: what was the intention of the 2018 Commission?

LITHGOW: The goals of the Commission were to look at the arts – look at the urgent needs, look at issues like access to the arts in education and the arts in the creative workforce, which is the focus of the second of our two reports. And then halfway through our work the pandemic hit, and suddenly everything that was an urgent problem when we created the Commission and began examining, working, and researching became a catastrophic problem. The mission of the Commission changed radically. Our recommendations are all about helping the arts come back and helping artists regain their livelihood. It is difficult because, of course, we are dealing with public policy, and we are making recommendations at the federal and state levels. The arts are notoriously a political football if you look at the history of the NEA over the last forty years. The heyday was back when John F. Kennedy held concerts in the East Room of the White House with famous artists, such as Pablo Casals. The arts have struggled terribly since then, and so the Commission is responding to that need.

COLBERT: Thank you, John. Deborah, how did we get to this point where the arts have become underfunded and undervalued? Is it merely budgetary, or is there some hostility to the arts?

RUTTER: I don’t believe there is any hostility to the arts, Stephen. And I appreciate your asking the question in that way because, in fact, we know that most Americans understand and believe in the power of the arts and the arts experience. More than 80 percent of Americans say it is important and valuable to have the arts a part of our lives. The issue is about funding. To add to what John said, the NEA was founded in 1965 and it had an appropriation in its first year of $2.8 million – small money in some ways. But if you think about that money and advance it with the value of the dollar, it would be many times greater than the $167 million appropriation it has today. So, it is budgetary, and unlike much of the rest of the world, the NEA is not getting support of the same degree from across the leadership at the federal, state, and local levels. It is always struggling to keep going forward. It is about priority and the value given to the arts.

COLBERT: Natasha, I love poetry. I go to it for the same reason I go to the Scriptures: for centering, to give me a broader view of my own experience, and to open myself up to other people’s experiences so I can understand the fullness of my humanity. From your point of view as both a poet and an educator, how does poetry make for a better citizen?

TRETHEWEY: If Scripture is the sacred word, then poetry is the living word. And because poetry involves the intimacy of a single voice speaking to us across the distances, it allows for us to hear each other in different ways than we might otherwise in a world full of sound bites and clichés. It asks that we be more observant, more empathetic. It asks us to understand things not only on a literal level but through the possibilities of figurative language and imagery that can make the mind leap to a new apprehension of things. When we hear each other differently, it can make better citizens of us. It can make us understand the world and see it through the eyes of someone else. One of the things that poetry did for me and what I try to show to my students is that there are poems out there for all of us that either speak to us or for us, and that when we make our own, we join in a conversation that is ancient and ongoing. We add our voice to the song, and that is participating in citizenship.

COLBERT: Following that idea of citizenship, there is so much worry, and I think well founded today, that we are in danger of not having shared values as citizens of the United States and as citizens of the world. But especially in the United States, not having a common set of values would be a dangerous thing for us. John, I am wondering what role the arts in all their forms play in outlining or guiding us to those common values?

LITHGOW: I think the arts could play a major role, and to an extent they already play a role: there are certain arts phenomena that bring everybody together. When you have a colossally popular movie or a television show or a piece of music, there is a sense that this is a great American achievement that touches all of us, that we all share and are proud of. But there could be so much more of that. One interesting aspect of our Commission is the diversity of the Commission members, both geographically and in every other conceivable way. And beyond that, the Academy staff, a remarkable group, reached out across the country and assembled roundtables of people who had already created their many versions of what we were doing. Some knew each other because they had been brought together before, but many were unaware of one another. One of the recommendations in our creative workforce report is to create what we would call a policy exchange: the federal government would oversee a program that would put people in contact so that those involved in the arts, for example, in Alaska, California, and New Jersey, where incidentally Evie Colbert is active in the state commission for the arts, could create a unified voice. The biggest problem we have in this country is the word unification: bringing us together. Everybody has a strong sense of how divided we are and what a terrifying crisis that is. The arts are the best way of addressing that.

COLBERT: Is there an issue dealing with politicians who are being asked to fund the arts, support the arts, or focus on the arts? Artists tend to be iconoclastic, and political systems are often based on status. Is there anything threatening about the arts to those in power?

RUTTER: In my experience, no. In fact, there is a great deal of respect, a fair bit of awe, and as much interest in the magic of what is created by an artist. I get to stand side-by-side with many of the elected officials of our country, and they say to me, “My goodness, is that John Lithgow, is that really him? Do you think he would sign my program? Could I have a picture with him? Isn’t it amazing what he does?” And the same for Natasha: “How is she able to be so facile with these words?” I don’t believe that you can broadly say that there is an issue of politics with the arts and with the artists themselves.

COLBERT: I’m so glad to hear that because I have hosted the Kennedy Center Honors a few times, and one of the things that always struck me is that the evening is completely apolitical. You look out at a sea of people, and I know all their faces. I know all their political positions, but they are there in support of the arts. It gives me hope when I see that.

LITHGOW: We in the arts are in the empathy business, and I have a certain empathy for policy-makers and elected officials. They are, of course, overwhelmed; I mean just look at the politics of this week. These people are experts at these intractable problems no matter what their political point of view, and they wrestle with them constantly. But they do not consider themselves experts on the arts at all. I don’t think they see it as part of their bailiwick in D.C. And so that is one of our great responsibilities: to persuade them. The arts should be just as much at the center of our lives as our economy or our foreign policy or our domestic policy. Not only are the arts essential and almost existential, but they are fun and a joyful subject. I mean artists very much want to go to Washington and be heard. We are just one of many organizations and groups that want desperately to be heard in D.C. and that want to change people’s minds for the better.

COLBERT: Natasha, creating a piece of art can be a taxing and challenging thing to choose to do for your life’s work, but it fills you with vitality. Unfortunately, the pandemic made it even harder for people who are trying to make a life in the arts, especially arts that are collective arts. Is there any advice you give to people who may have been ready to throw in the towel after eighteen months of this pandemic, who find the challenge of living an artist’s life too hard?

TRETHEWEY: That is a hard question because, of course, people need to make a living. In our report we talk about how hard it is for artists to make a living. But I also believe it is something you must do because you have to do it, because you are called to do it. Because if you didn’t do it, a little part of your soul might die. For me, a little part of my soul might die if I didn’t write poetry.

COLBERT: Is there any art you turned to during the pandemic for your soul’s ease?

TRETHEWEY: Well, I turned constantly to poetry. And recently I turned to the poetry of Muriel Rukeyser, who first became aware of what was happening in the world when she was about five years old. She remembers the false armistice, but she was also living in the middle of a pandemic, the first one we had a hundred years ago. And so to turn to her work and to see how she came out of that to write and to deal with the challenges that we face even now is something that helped me contend with this moment that we are in.

LITHGOW: May I interrupt to give a shout-out to the book Natasha published during the middle of the pandemic? She wrote a memoir called Memorial Drive, which is one of the great books of last year and one of the most nakedly personal pieces of writing I have ever read. I didn’t want the moment to pass without saying that.

TRETHEWEY: Thank you.

COLBERT: Deborah, tell me about Turnaround Arts at the Kennedy Center. What is the purpose of the program?

RUTTER: Turnaround Arts is a special program created by artists who want to help the lowest performing schools across the country integrate the arts into their curriculum and into the culture of the school. As the celebrity artists, they are the sponsor, the support mechanism, and the cheerleader for that effort. The program is now over a decade old, and we are in eighty schools across the country and in several different districts. Some of the districts have just truly exploded, and you can see remarkable turnaround in the success of the schools. We are not trying to produce more actors or more musicians, though we are probably creating more poets. More importantly, this program has helped with school attendance and graduation rates. It is a great program and an exemplar that an arts curriculum does serve all these other needs as well. It is not about having a student orchestra, but about embracing the arts and integrating the arts into the school day.

LITHGOW: I think it is worth saying that the very term “turnaround arts” came from the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities, which was disbanded. One of the Commission’s recommendations is to reconstitute that committee at the federal level, indeed within the executive branch of the federal government. If you create a conduit for it, remarkable things will happen.

COLBERT: On that hopeful note, the Commission describes its work as a call to action that embraces optimism. What gives you hope right now about the arts, especially considering this past year? John, I will start with you.

LITHGOW: One thing that gives me hope is the fact that art did not stop last year. Artists found ways to express themselves publicly and privately. They made great use of the Internet. The explosion of love and enthusiasm was heartening. I am in New York, and I am seeing the New York theater come back to life. There is a hunger for theater now, and that gives me enormous optimism. Art is coming back.

COLBERT: Natasha, what gives you hope?

TRETHEWEY: Well, it is very similar to what John said. The idea that during the pandemic, people who didn’t think of themselves as artists turned to art. They viewed and witnessed art on Zoom. And we had many more people on Zoom for a poetry reading than we might have ever had in person because Zoom can travel around the world. We had people tuning in, and we had people who might not think of themselves as artists turning to make art themselves and to make poems. We need to honor the impulse that we have to make something.

COLBERT: Deborah?

RUTTER: I think art became more personal and more intimate. As we spent more time by ourselves or in small spaces with others, it gave us an opportunity to think about ourselves, our role, and the ways in which we value the quality of our lives. As a result, as Natasha said, there was more experimentation and exploration. The Kennedy Center, for example, had many people participating digitally who had never been connected to us before. It was an opportunity for people to explore, learn, and become engaged. As John said, people are coming back. There is an enthusiasm to engage, to see our favorite artists, to experience a live performance. It is miraculous, and we are really excited to welcome people back to the Kennedy Center. I think it is about resilience. As John and Natasha mentioned, art will always survive, but we must give access and opportunity to all people. We must give greater equity of support across the art forms and across the country. This is a moment for us to understand from a social justice perspective that artists of color, no matter their art form, need support. As Natasha said, an artist will always go back to doing their work because it is a part of who they are, but we must honor them for that and not take it for granted that they will do it because they need to do it just as much as they need to breathe. We need to understand that they deserve to be supported fully, and that is among the recommendations in the Commission’s report.

LITHGOW: We have a wonderful example of an artist who reimagined his work last year and managed to discover new things about it. And that artist is Stephen Colbert. You invited people into your home and made late-night television a completely different genre for that period of time. I have a friend who is a Peabody voter, and she said a major reason you were given a Peabody is because of how you responded to the pandemic last year. You are an artist, Stephen.

COLBERT: Well, that’s lovely for you say, John. Thank you, Deborah, Natasha, and my friend John for giving me an opportunity to talk with you today. And thank you for the work that you do to support the arts, shining a light on the value of the arts, not just for their creativity but for their connection that gives us access to ways that we can explore our shared humanity. It is about loving each other. So, thank you for the love you have given, and for the ability of other people to express their love. I hope to see you all soon.

Q&A Session

Allentza Michel

Allentza Michel was Program Officer for the Humanities, Arts, and Culture at the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

I would like to thank our Commission cochairs for a very rich discussion with Stephen Colbert. We have many questions submitted by our audience; we will do our best to get through as many as we can in our remaining time. Our first question is: “Can you say more about the vitally important role of the humanities and the arts in strengthening our democracy?” Let’s start with John.

LITHGOW: We have touched on some of this in our conversation so far. The wrangling that goes on over policy forestalls action. It is difficult for people who advocate for the arts to persuade anyone that the arts have a place on the agenda with policy-makers. What we say constantly is give us some attention and we will persuade you. As Stephen Colbert mentioned when he talked about hosting the Kennedy Center Honors, politicians have much more in common than they think. They are public servants, and public service is a matter of working things out together. The essence of art in many cases is collaborative: a performer working with an audience, the transaction between a storyteller and a listener. They are all communal experiences that persuade us we are part of the human family. The great difficulty we have is retaining our identity as American brothers and sisters. It is a sad reality that the moments when our country has most completely come together have been moments of tragedy and crisis. The two world wars, 9/11, even the financial crisis of 2008 when everyone was suffering together: those are the moments when we feel American, when we feel bonded, when we feel we are in this together. Unfortunately, for whatever reason, we are not capable of feeling that right now. So much of our conversation in the Commission was about what the arts can do for young people and audiences who are brought together in a common experience. We know what a gorgeous art exhibition can do even when people view the artwork online. Those are the moments when you feel part of a community, and community is the operative word these days. We have to be a national community, and somehow, we have lost track of that. I think we can regain it through the things we love.

MICHEL: Thank you, John. Natasha, how can the arts uplift and support democracy?

TRETHEWEY: The arts have the potential to bring us together because they show us in our desire to participate in them as an audience or as a maker not that we are different but how we are alike. I want to read something that Toni Morrison wrote about writers thinking, but it applies to the arts in general. “Certain kinds of trauma visited on peoples are so deep, so cruel, that unlike money, unlike vengeance, even unlike justice, or rights, or the goodwill of others, only writers [and I will add artists] can translate such trauma and turn sorrow into meaning, sharpening the moral imagination.” I think the arts sharpen our moral imagination so that we see each other in all our full humanity, and that can bring us together.

MICHEL: Thank you, Natasha. We have a few questions about the pandemic: “Can you elaborate on the impact the pandemic has had on the arts? And can you describe some of the traumas and how long we think it might take to recover?” Deborah, would you like to start?

RUTTER: This is an important question. At the Kennedy Center, early in 2020, we were feeling proud of ourselves. We were feeling strong institutionally; we were excited about the creative expression of our artists and the diversity and variety of our programming. We had just opened a new extension to our campus, The REACH, which was welcoming another aspect of engagement with the arts besides just being a spectator. It was inviting activity, engagement, participation, learning both from artists and with artists and audience members. And then on March 11, 2020, we shut down for what we thought would be a few weeks, perhaps a few months, and it turned into eighteen months. In a given year, we present or produce two thousand performances at the Kennedy Center. Over that same time period in 2020, we produced less than two dozen. We normally would have employed three thousand individuals with W-2s and another seven hundred with 1099s. So nearly four thousand individuals – artists and creative culture workers – were employed, but over a similar period of time in 2020, we had under five hundred, and that was because we continued to employ our two orchestras. Think about the thousands of people at the Kennedy Center who did not get paid. This story is personal for me. It was a devastating experience that shined a light on the fragility of the economic model that sustains the creative life of America. Because it is not just people at the Kennedy Center – the dancers, actors, singers, spoken-word artists, and visual artists – who were not employed. It was all the people around them as well, and that is true across this country. People left the field altogether or had to make a living doing something else. It demonstrated the lack of a safety net for our arts organizations and for the artists themselves. Many who strive to be an actor or a successful dancer or an artist of any kind knew this all too well. The pandemic demonstrated that what gives our lives color, meaning, and connection was lost. Those who provide it are undersupported, and we as a country need to think hard about how we celebrate and support artists. The Kennedy Center opened up about five weeks ago, but we are 25 percent smaller than we were in the year before, and I think it will likely stay that way for a period of time. As I look at my colleagues in organizations both in the region here and around the country, I know that we are all doing less. I worry that it will take us a good, long period of time before we can come back to anything like what we were in 2019. And this is actually a time when we need to come together more, not less. The arts shine a light on who we are as individuals and who we are as a community. And we are craving that. We need support at the very highest level for this kind of a safety net for artists and for the arts broadly across the country.

MICHEL: Thank you, Deborah. Several attendees have asked, “What are some concrete things that we can do to bring more resources to the arts in our schools and in our communities? And how do we convince lawmakers to put greater value in the arts and in culture?”

LITHGOW: We have two wonderful reports from the Commission that people can take to their school superintendents, local arts commissions, state arts commissions, and even to their congresspeople to show the wonderful excitement of combining the arts with everything that students are studying in school. There are people in office who can change things.

RUTTER: As somebody who receives documents and reports not infrequently, I would like to encourage folks to look at the Commission’s reports. There are strategic, key messages in these reports and good examples of the power of the arts on the development of young children. The arts build empathy, understanding, and creativity, which in turn creates a better workforce. I encourage everyone to take the time to look at these reports, either the hard copy or the online version, and deploy the information that is in them.

LITHGOW: And they are gorgeous to look at, by the way. We haven’t compiled just a bunch of gray data; we have included the voices of very passionate people, who will tell you why the arts are important to them.

MICHEL: Thank you, John and Deborah. We have time for one last question: “How have the panelists’ lives been enriched by everyday arts such as folklife, blues, bluegrass music, gospels, powwows, mariachis, and the like? How can the celebration of these forms of art, what is normally considered folk art or folklife, help galvanize an appreciation of a diverse nation?”

TRETHEWEY: That is a terrific question. It is hard to say how my life hasn’t been enriched by so many different forms of art. I think someone pointed out earlier in the program how art is around us even when we don’t notice it is there. I want to go back to something I said earlier about my grandmother, who I mentioned was a drapery seamstress who had this need to make beauty both in the craft of her work but also with how she decorated her home. She hung fabric and transformed a hallway that otherwise would have been dark. That memory still enriches me because I think it is from watching her that I learned something about precision, that I learned something about industry and the making of things. I think about the pedal she pumped on her sewing machine, the sound of jazz on her radio, and the precision with which she could make a stitch. I hope that I can make a line of poetry as precise and beautiful as her stitches.

RUTTER: One of the great things about the Kennedy Center is our daily programming called Millennium Stage, which transformed during the pandemic to Couch Concerts and Arts Across America. One of the unique things that I really did not expect when I came to the Kennedy Center was the close relationship with all the embassies in Washington, D.C. One of the ways we service that relationship is by hosting and presenting touring artists from around the world, who present their folk art and share their ethnic heritage. It makes Washington, D.C., an extraordinary place because of the access to all kinds of sounds, language, dance, and colors from around the world. And this enriches not just our lives, but it inspires the artists in the building to think about their creativity, their art making, and the collaboration that comes as a result of being with people from different cultures, seeing different art forms coming together, and creating something new. I come from the world of classical symphony orchestra, and I am beyond thrilled to see the way orchestras and ballet companies are embracing and welcoming the sounds and sights of other art forms. I was glad that John celebrated Stephen Colbert as an artist because I think comedy is an art that compares with any other form of spoken word; it is just another vehicle of communication. One of the ways in which we need to dispel rumors, myths, and legends is to say art is what we love and appreciate, and it is what makes our world richer.

MICHEL: Thank you, Deborah. Let me ask John for some final comments.

LITHGOW: First, let me speak very briefly about how I have been affected by the arts in my life. I am a performer, but I am also a great audience member. I am voracious and curious. I find every one of the arts absolutely exhilarating. I go out and I find what’s hot; I find what’s exciting. As I mentioned to Stephen Colbert, in every town that I visit I go to the art museum. I have been in New York for about three weeks, my first time in eighteen months, and I have seen four plays and two operas, and I have performed twice on stage. I want kids, young people, and adults to have absolutely as much appetite and curiosity for the arts as I do and to put down their devices and go out and see live human beings execute art.

Today, we have shared with you a good deal about the Academy’s Arts Commission, the first of its kind in the Academy’s long history. And through the good offices of Stephen Colbert, we have spoken about the two major policy reports that we released this month: one on the importance of the arts in education and the equality of access to the arts for all students, and the other on the health and livelihood of the American creative workforce. I would like now to introduce you to some of the Commission members and a few of the artists in the Academy’s membership who have supported our work over the last three years. And what better way to showcase these major figures in the creative arts than to tap their own creativity in what we have titled Mixtape. It is an online gallery that showcases the energy and talent of many artists. We invited each of these creative people to produce a video, which portrays what they are working on at this very moment. The results have been delightful, inspiring, and sometimes astonishing. We have created a five-minute montage drawn from these lively creations to share today as part of the celebration of the Commission’s work. The full Mixtape is available on the Academy’s website. The brief clips of poetry, stories, songs, videos, and artwork create a portrait of the broad creative spectrum of this group. Contributors include John Legend and Yo-Yo Ma, Hawaiian hula master Vicky Holt Takamine, and Rahele Megosha, a high school senior who won the 2021 Poetry Out Loud National Competition. You will know some of these people from their notable achievements, but they may surprise you with how they have stepped out of their creative comfort zone. Our Commissioner Jeffrey Brown from PBS NewsHour recites his own poetry, and our Commissioner Francis Collins from the NIH sings and plays the guitar. I don’t act but rather I scribble satiric portraits in ink. Now this took a lot of nerve on our part, but it is part and parcel of our larger enterprise. We have fearlessly put ourselves on display as part of our call to action. It is our grand ambition to awaken everyone to the importance of the arts, and we invite all of you to step out of your comfort zones to campaign for the arts.

[Event participants watch a five-minute montage of Mixtape.]

OXTOBY: I would like to thank all the Commissioners and Academy members who contributed to this exciting project. I hope you will explore the full Mixtape online and share it within your networks. As we near the end of our program, allow me to invite Natasha to close in the same way we began, with a poem.

TRETHEWEY: Thank you again for joining us. As benediction, I offer another poem by Lucille Clifton entitled “blessing the boats.”

may the tide

that is entering even now

the lip of our understanding

carry you out

beyond the face of fear

may you kiss

the wind then turn from it

certain that it will

love your back may you

open your eyes to water

water waving forever

and may you in your innocence

sail through this to that

Lucille Clifton, “blessing the boats,” from Blessing the Boats: New and Selected Poems, 1988–2000. Copyright © 2000 by Lucille Clifton. Reprinted with permission of BOA Editions, Ltd., www.boaeditions.org.

OXTOBY: Thank you, Natasha, and thank you, John, Deborah, and Stephen. This has been a wonderful distillation of the work of the Arts Commission and an illustration of the power of the arts. The Commission’s work was designed to live on long after our final meeting. I encourage you to visit the Academy’s website for more resources, including the two reports, Mixtape, and recordings of previous events. Please share these resources with colleagues and friends. And continue to think about the way in which the arts and artistic workers can be centered in your own lives.

© 2021 by Stephen Colbert, John Lithgow, Deborah Rutter, and Natasha Trethewey

To view or listen to the presentation, visit www.amacad.org/events/elevating-arts-America.