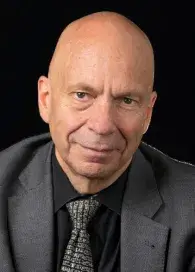

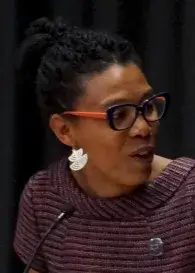

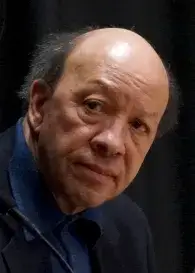

On April 1, 2019, the American Academy and the Whitney and Betty MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies at Yale presented their first joint public program, which featured a conversation between David Blight (Class of 1954 Professor of American History and Director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale University) and Robert Stepto (John M. Schiff Professor of English and Professor of African American Studies and American Studies at Yale University). The program, which served as the Academy’s Morton L. Mandel Public Lecture, included a welcome from Ian Shapiro (Sterling Professor of Political Science and Henry R. Luce Director of the MacMillan Center at Yale University). Crystal Feimster (Associate Professor of African American Studies, History, and American Studies at Yale University) moderated the program. An edited version of the discussion appears below.

I am delighted to welcome you here today for this joint venture between the MacMillan Center and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Let me say a few words about the American Academy. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, James Bowdoin, John Hancock, and others who helped establish the new nation. The Academy’s founders believed that a strong republic must be grounded in open discourse, engage scholarship, and promote an informed and active citizenry. Over time, the American Academy’s membership has expanded to include leaders in all fields and disciplines, many of whom work together through the Academy to address topics of both timely and abiding concern. The Academy now has about five thousand members in the United States, including two hundred or so in the New Haven area. The Academy holds meetings around the country and conducts research projects out of its home offices in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the areas of the arts and the humanities, American institutions, science and technology, education, and global security.

Tonight’s program is part of the Academy’s Morton L. Mandel Public Lecture series, named in honor of the Jack, Joseph, and Morton Mandel Foundation’s generous support of the Academy. Our event was organized by the Academy’s New Haven Program Committee, a group of Yale-based Academy members that convenes in partnership with the MacMillan Center periodic discussions and research presentations on issues of importance. It is my pleasure now to introduce our moderator, Crystal Feimster, who will in turn introduce the panelists and lead us into our discussion this evening. Crystal is an Associate Professor in the departments of African American Studies, History, and American Studies. So welcome again and thank you, Crystal.

Good afternoon and welcome. I want to begin by thanking the New Haven Program Committee of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and Yale’s MacMillan Center, especially Frances Rosenbluth and Ian Shapiro, for helping to organize this event. I have the honor and the great pleasure of introducing two of my colleagues, Professor Robert Stepto and Professor David Blight.

Robert Stepto is the John M. Schiff Professor of English at Yale, and a member of the Yale faculty in African American Studies and American Studies. He is the author of many publications, including A Home Elsewhere: Reading African American Classics in the Age of Obama; Blue As the Lake: A Personal Geography; and From Behind the Veil: A Study of Afro-American Narrative. This is Professor Stepto’s last semester teaching at Yale. We celebrated him about a year ago, and many of his students came back for that celebration. I have to say that my office is on the fourth floor with Robert and it is going to be quite sad when he is not moving through those halls. I’m hoping he is not going to give up his office any time soon.

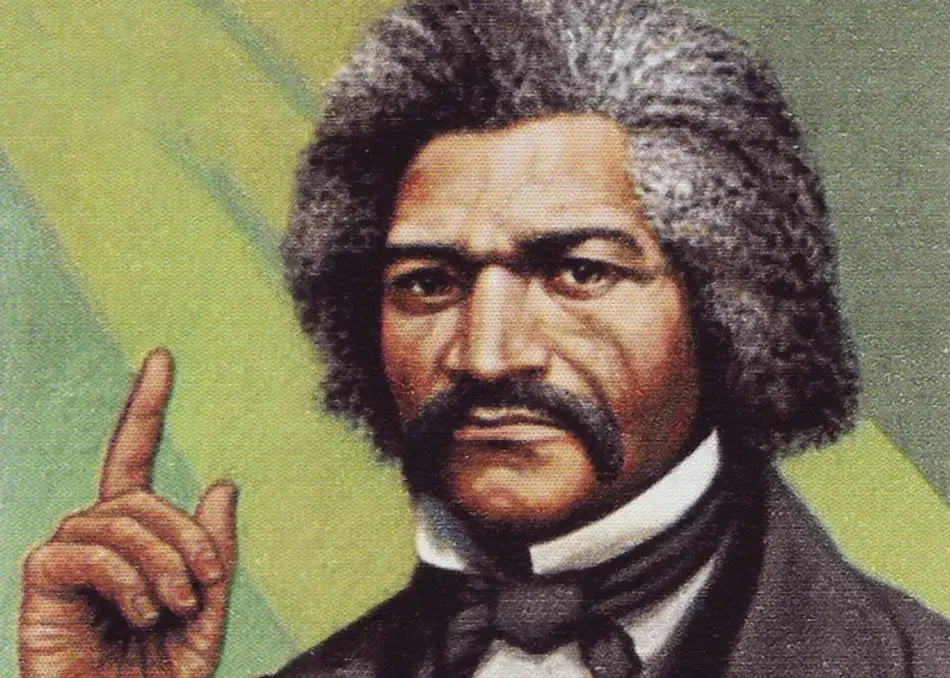

David Blight is Class of 1954 Professor of American History and Director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale University. He is the author of numerous books, including A Slave No More: Two Men Who Escaped to Freedom; Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory; Beyond the Battlefield: Race, Memory, and the American Civil War; and, most recently, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, which has been awarded the Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize and the Bancroft Prize. This evening we want to have a conversation about Frederick Douglass as a writer, literary scholar, and artist. As Professor Blight’s mammoth biography of Douglass makes clear, there is much to discuss, ranging from Douglass’s three autobiographies and the novella Heroic Slave, to his hundreds of short-form political editorials and thousands of speeches. In Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, Professor Blight writes, “The reason we remember Douglass is because he found ‘the word.’” And as Professor Stepto has written, “Somehow, Douglass intuitively knew that to write and craft his story as opposed to telling it was to compose and author himself.”

I would like to begin our conversation by talking about what made Douglass such a brilliant writer; in particular, how did Douglass become a writer, what were his style and motivations, and how did he contribute to American literature more specifically? Both Professor Blight and Professor Stepto can speak as literary scholars and historians, but I also know that they are interdisciplinary scholars, working at the intersection of African American studies, history, English, and American studies. Let me turn things over to them, and they can choose to engage that question however they like.

It seems to me that Douglass was an extraordinary writer because of his relationship to words, and I am putting it in that sense because we are talking about someone creating himself through writing but also through the spoken word. One of the things that I have been thinking about particularly after reading David’s latest book is Douglass’s performance of words: performance in terms of writing text, but also performance in terms of the speeches he gave at anti-slavery rallies, in churches, and so forth. One thing that is very clear to me is that Douglass got a lot from biblical stories and biblical language. He found images, metaphors, rhythms, and so forth. Certainly, one thing that he got from the Bible were the various prophetic stories. I hope David will touch on this since he has written about it and the ways in which Douglass was a prophet through his mastery of words.

I started reading Robert’s essays on Douglass when I was in graduate school. He wrote one essay in particular that I quote in my edition of the Narrative that showed that the text was what Robert called “a story of ascendancy” – going from slavery to freedom – and that the rhythm of the book, the movement of the book, the creation of the self in the book, and the character called Frederick Douglass were always ascending. And that is Douglass’s great skill as the manipulative autobiographer that he was, always imposing the self on us that he most wants us to use.

As Robert just said, Douglass is all about words. We would not be talking about him if it were not for the words – millions of them in thousands of speeches and in three autobiographies. If you are a biographer, never trust anybody who writes three autobiographies because they are always there in front of you, imposing themselves on you.

For historians, there is a lot to consider. We might discuss how he came by his literacy. He seized literacy as a boy. And then as an early teen, he discovers the Columbian Orator, a book of speeches but also especially a manual of oratory that he has in his hands by the time he is twelve years old. This is the most important possession he ever had in slavery. He gains a further kind of literacy from gathering anything he could find to read and then by listening to sermons. He learns a type of sermonic language, that King James language, as a kid first and then as a teenager – he names four churches in Baltimore that he attends while he is still a teenage slave. He not only seized literacy, he weaponized words.

But it took him time. He doesn’t come out of slavery a fully formed orator and certainly not a fully formed writer – that takes time for anybody. But he was proud of himself as a writer. In fact, there is a letter that he wrote about his first published article. It is in the late fall of 1844, he is just about to start writing the Narrative in his little cottage up in Lynn, Massachusetts. He writes to an editor who has just accepted a short article of his, and the letter ends with a line that goes something like, “Oh, but to write for a book,” which was his way of saying, “I wonder if I could write a book.” I am sure many of us in this room will never forget writing your first book and what it looks like and the altar you made for it in your home or your apartment – that’s what I did and still do. But, oh to write for a book. And here was a very young man, twenty-six years old, a former slave. Black people were not supposed to be people of literacy, people of literature. “Could I write a book?” Could he ever. And that winter, he sits down and writes the greatest slave narrative.

Robert Stepto

You are correct that he was very clear that it wasn’t enough to be able to read; you needed to be able to write as well. He wrote that essay in 1844, then the first Narrative comes out in 1845, and soon thereafter he started talking about a newspaper. And that came before My Bondage and My Freedom. The writing was very important in that regard. I also want to mention that he was also creating himself, if you will, through his speaking. One of the things that has been on my mind lately – and I’m really surprised I hadn’t thought about it earlier – is that Douglass is speaking and writing, performing words, and creating himself. And when I say perform, I am also talking about how he dressed himself, which we know something about by looking at his photographs. He is doing all of this during the period in which minstrelsy is being created and is coming about in this country.

Think about how he was presenting himself and the portrayal of race, which is different from what was in the minstrel shows – that was something to see and something to contrast. The first minstrel group, the Virginia Minstrels, was created in 1843. Now, connect that date with when Douglass was writing his first autobiography in 1845, speaking in churches in New Bedford and elsewhere, and creating the newspaper.

Let me add a couple of other things. We learned in My Bondage and My Freedom that sometime after his mother passed away, he discovered that she was literate. What does that mean for him not only to discover that an African American was literate, but that that person was his mother? What would it mean to him on some level that he is part of the next literate generation, that he was not some kind of anomaly?

Let me mention another elder who was important in this story, whom he describes in My Bondage and My Freedom. That person is Uncle Lawson, a black man he meets when he gets to Baltimore. One of the things I suggested in writing about the Narrative was that in meeting Uncle Lawson, this was an opportunity for him to find a black father and to go to church with that black father and to be literate with that black father.

David Blight

In Bondage, he calls him Father Lawson. That is terribly important. He encounters this Charles Lawson, who drove a cart to try to make a living. He was a Bible fanatic and yet he wasn’t fully literate. When he discovered this teenage kid who could read well, according to Douglass, he sat him down for hours and they would read out loud the Old Testament. Douglass doesn’t understand the Book of Job, if that is what he’s reading. He doesn’t understand Isaiah or Jeremiah, but he’s reading, and the cadence of that language is getting into his head as he reads with this old man.

Let’s talk a little more about the Orator. Where does this brilliance with oratory come from? Again, he’s not born that way, but he is already doing this while he’s a slave. He takes his Columbian Orator, this amazing book, this compilation put together in 1797 by Caleb Bingham, a Connecticut schoolmaster who ended up at Dartmouth and then in Boston. He published The School Reader in 1797. It went through twenty-eight or so editions over seventy-five years. It was even published: there is a Maryland edition that was published in the slave state. Most of the speeches are out of the Enlightenment tradition. There are some speeches from antiquity – Demosthenes is in there; Cicero is in there – but it is mostly speeches from the British and American Enlightenment about things like liberty and equality. The book has a twenty-page introduction that is a manual on oratory. It is a kind of how-to. It tells you how to gesture with your arms, your shoulders, and your neck and then how to modulate your voice from lower to higher tones. It tells you how to build to crescendos, and it has a whole section probably from Aristotle about how the orator must reach a moral message, must meet the heart and the spirituality of the audience. Douglass used this manual to teach his buddies on the Freeland Farm, one of the places he was hired out to on Sunday afternoons when he was seventeen or eighteen years old. They would go off in a brush arbor and he would teach them oratory, and then they would recite. So, he was already practicing. But what does every kid want? Every kid wants to learn what you are good at so you can be better than the other kids. Dribble behind your back or in his case it was oratory. By the time he comes out of slavery at age twenty, he has already practiced this. What is he doing in New Bedford by the time he is twenty-one? The local AME church has him preaching and that is where he gets discovered two years later by some Garrisonian abolitionist from Boston. “Boy, there’s this young black guy down at that AME church in New Bedford. You got to go see this kid.” He is still not fully formed, but when he does get hired and paid meager wages in 1841 by William Lloyd Garrison’s organization, he goes out on the anti-slavery circuit, and he is twenty-three years old. He is on the road with this troop of abolitionists and his most famous speech in those first few years is a speech that became known as “The Slaveholder’s Sermon.” This was Douglass mimicking a slaveholding preacher, using those passages from the Bible: slaves be loyal to your masters and so on and so forth. He would perform. He would mimic accents. He would prance around the stage, and it was a good performance. Abolitionist meetings would always be organized around or against a resolution, whatever the six resolutions were that day, and frequently – I have numerous press accounts of this – someone in the audience shouts out, “Fred, do the sermon.” And he performs the sermon and the audiences would be weeping and laughing and clapping, and that is how he takes the abolitionist oratorical platform by storm. At the beginning, he seems to be second fiddle to Abby Kelley, who was the first real woman star of the abolitionist circuit, but within a couple of years, he becomes the marquee and it would sometimes be a problem because other abolitionists didn’t always like to appear with him because he was just too good.

Crystal Feimster

Professor Stepto, if I remember your research correctly, you make the point about the shift: from performing the abolitionist work to writing the book. You make the argument about the power of the written word and what he does with that written word that he is not able to do in those abolitionist performances. I am wondering if you could speak to what was at stake for him not just to stick with those performances but to have the written word on the page.

Robert Stepto

Let me begin by mentioning and perhaps reminding you that a famous woman in his autobiographies, an abolitionist, came up to him and said in so many words, “You know, you need to sound more like a slave. You’re going too far. Get a little more of the plantation into your speech and all of that.” If I’m not mistaken, he admits hearing that specifically from a Garrisonian and I’m sure that that had something to do with why he eventually moved away from the Garrisonians. There were lots of reasons, including political reasons and so forth, but I would say, among other things, that part of his response to people saying to him, “Why don’t you sound more like a slave?” was first, he wasn’t going to do that, and second, he was going to write, which most slaves were not doing.

Crystal Feimster

Professor Blight, one thing that you mentioned is the business about Douglass being attracted not just to the Bible, but specifically to the prophets, to Isaiah and Jeremiah and so forth, and having them serve as models for him in certain respects. Could you talk about Douglass and prophecy?

David Blight

One of my problems in writing the book Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom over many years was coming to some sense of confidence with using the word prophet. “Prophet” is a big word and you don’t throw it around loosely. Douglass writes and speaks in a language that sometimes just hits you between the eyes, with a metaphor, a single sentence, or a paragraph that transmits you somewhere. You cannot read Douglass and not see the Bible, especially the Hebrew prophets. With a few exceptions, his speeches always have something from Isaiah, Ezekiel, Jeremiah, or Amos; something from the New Testament, but usually from the Old Testament as well, where Douglass learned his storytelling. The cadences of his voice are in the stories of the Old Testament. He made Exodus his own story, but this hardly makes him unique. Americans have been doing this ever since they have been Americans.

I don’t have any formal theological training and I had wished many times in the course of working on this book that I could get a year off to do nothing but read theology. So, I asked a few theologian friends what I should read on the Old Testament. One friend said to read Abraham Heschel, especially his great book called The Prophets, written in the 1950s. The first chapter has a hundred different ways of defining a prophet. Heschel’s template, of course, is the Hebrew prophets, but he was also reflecting on modern prophets. What Heschel helped me understand is that a prophet is not just somebody who predicts; prophets are often wrong. Prophets are human and they speak in words one octave higher than most of us can comprehend, and they find those words and the right timing and place to shatter us.

There are many other definitions that I took from Heschel as well as from Walter Brueggemann and Robert Alter, who wrote a terrific book about how the King James version of the Bible is the American text of the nineteenth century that many American writers – think of Melville, Lincoln, and others – owed their prose style to. Douglass would sometimes use direct biblical quotations, sometimes just paraphrases, and sometimes just single phrases from the quotations. What Douglass found in the Old Testament was storytelling and metaphor, as well as ancient authority and power for the claims he is trying to make about this American experiment, which is failing. One of the biggest themes in my biography is how steep Douglass was in the Bible and how his rhetoric and politics owe so much to the storytelling of the Old Testament. At one point, I even did a survey of which book of the Testament got used the most in his major speeches. Isaiah always comes up first, maybe because it is the longest book in the Bible, and Jeremiah is second.

Douglass would use the famous line in Isaiah, “There’s no rest for the wicked,” which comes out in different ways, forms, and uses. He used that over and over again when talking about slaveholders.

Robert Stepto

You have just reminded me of something that I read in your book: “For black Americans, Exodus is always contemporary, history always past and present.” That passage really struck me because Exodus certainly was always contemporary for Douglass, but, in fact, it is contemporary for us now.

David Blight

He is an exiled son, and when he thinks he has transcended that, he learns that he hasn’t.

Robert Stepto

Another thing that struck me is when you write about how Douglass employed, especially in the second autobiography, all manner of blood metaphors for the nature of African American history. Consider such phrases as “history that might be traced with a trail of blood” or, and here I am quoting Douglass directly, “Slavery put thorns under feet already bleeding.” The blood metaphors go on, and it is very graphic.

David Blight

In the first autobiography of 1845, he portrays a fight he has with Edward Covey, this overseer to whom he’s hired out, and it is the pivot of the book, no question. He spends about eleven pages on it in the Narrative. He spends thirty-five pages on it in Bondage and Freedom ten years later when he is thirty-seven years old and in the middle of the political crisis over slavery. He has broken from the moral Garrisonians, he has embraced the politics of anti-slavery, and he has even begun to embrace the possible uses of violence. And in the two pages in which he actually describes the combat with Edward Covey, there are fifteen uses of the word blood. Douglass is using the autobiography to attack not just the hypocrisy of the American nation, but its very existence. And he doesn’t know what is coming. He is a prophet who cannot predict any better than the next, but blood metaphors are all over that book. He is desperate by the middle of the 1850s for solutions that are out of grasp and yet he uses the literary form. He makes a literary act into a political act through autobiography as well as or better than any American who wrote a memoir in the nineteenth century, and perhaps any American who has ever written a memoir.

Robert Stepto

One of the things that occurs to me as you remind us of all these things is that Douglass, as time went by, learned a certain meaning and substance for what I am going to call the V words: victory, violence, and the vote.

Crystal Feimster

David, you have said about autobiography, and I want to quote you: “A great autobiography is about loss, about the hopeless but necessary quest to retrieve and control a past that forever slips away. Memory is both inspiration and burden. Method and subject, the thing one cannot live with or without. Douglass made memory into art, brilliantly and mischievously employing its authority, its elusiveness, its truths, and its charms.” Would you talk a little bit about what makes Douglass’s second autobiography so brilliant and how he is using memory not only as a method, but as a strategy?

David Blight

First, thank you for reading the book so carefully. Bondage and Freedom is four times as long as the Narrative. He is a much more mature writer by then. Just a quick aside, every major speech of Douglass’s is in the form of a text. They are all written. And by the 1870s and 1880s, they are in typescript. He wasn’t an orator who just spun things off the top of his head. In fact, I’m absolutely convinced Douglass didn’t know what he thought about something until he went to his desk and he wrote it.

Bondage and Freedom is a more political autobiography. That sounds rather vague, but he is writing it after he has become a political abolitionist. He embraced, first, the Free Civil Party and then the Liberty Party and he is now trying to understand how to embrace the new Republican Party. He has come to believe that slavery cannot be destroyed without somehow altering the law, political institutions, and political will. He doesn’t exactly know how that is going to happen and he is not comfortable yet with the Republicans, but it is a book that is arguing with American voters.

In addition, he has begun to embrace violence and the possible uses of violence. He never had a theory of how violence was supposed to overthrow slavery. He had a long relationship with John Brown. By my count, they met eleven times, but he had the good sense not to join John Brown in 1859. Bondage and My Freedom reads, at times, as a story anticipating possible violence in the country. This is what he argued in his famous Fourth of July speech just a few years earlier. Bondage and My Freedom is an update of the Narrative. In it he recounts ten more years of his life – he wrote the first Narrative before he goes to England. He tells the story of how Ireland, Scotland, and England transformed him, brought him a whole new set of friends and financial supporters whom he has never given full credit to, particularly Julia Griffiths, who became his assistant editor and made his writing life possible in some ways. He has emerged as a political and constitutional thinker, and he talks about that transformation by telling tales of his life. He now has a revolutionary voice that is warning the country. That voice will change again, in his third autobiography, Life and Times, some thirty years later, and give way to a flattened gilded age, of a man summing up his life.

Five thousand copies of My Bondage and My Freedom sold in the first two days, which says something about Douglass’s notoriety and fame; it sold eighteen thousand copies in the first three years. That is an incredible feat in the nineteenth century, especially for a book that is 460 pages long. And he sold each copy for one dollar. He would take two of his sons with him on the road when he was giving speeches and they would sell the book among the audience. Douglass had to be a great marketer, because this is how he was making a living from 1841 when he goes on the lecture circuit to 1877 when he gets his first federal appointment in the District of Columbia from President Hayes. He never made a dime except by his voice and his pen, and his British and a few American financial supporters. Yes, he had some patrons. He didn’t always give them credit except privately. I always tell my students that being an abolitionist is not a good career move.

Robert Stepto

I would like to go back for a minute to the blood imagery and the blood metaphors. One thing that I forgot to mention is that Douglass talks about how people were harmed. There is a fascinating early moment in My Bondage and My Freedom when he mentions a white woman by the name of Ms. Lucretia. He remembers her for two distinct reasons. First, she would give him a piece of bread and butter every now and then, especially if he came up to her window and sang. And second, he got into a fight, I believe, with another young man named Ike and he specifically tells us that Ms. Lucretia was the one who brought him inside and cleaned him up. So that is another side to all of it. There are the people who spill your blood, but there are also the people who will clean you up and Ms. Lucretia is remembered in those terms.

David Blight

And there are ways, Robert, in which he came to trust women in his life that he did not necessarily trust men. I mean that is not always an easy claim to make, but he developed trusting relationships with women more than he ever did with men. And it may not just be Lucretia who brought that about, but he does say that she is the first white person who ever invited him inside.

Crystal Feimster

In thinking about the blood metaphor, he opens the first Narrative by talking about the blood of his Aunt Hester. Would you say something about how that gets worked out in his writing and his politics.

Robert Stepto

Let me begin by saying that when you think of the full range of his career and what he would write, it is very striking that the first autobiography would begin with what happened to Aunt Hester, that that kind of atrocity would be there. You might even say it is sort of a scripted moment. I’m supposed to tell you about slavery. Let me begin with how my Aunt Hester was beaten by her own master, who might have been her father.

Crystal Feimster

And this is the moment when he realizes his enslavement, with her blood dripping onto the floor.

Robert Stepto

What I was trying to suggest a minute ago is that when he begins the next autobiography and then the last one, he doesn’t begin with Aunt Hester. Though interestingly enough, in the beginning of My Bondage and My Freedom, he does once again start with family. He begins with his grandmother and grandfather, with whom he lives. Grandmother is the mother of five daughters, one of whom is his mother, and all five daughters are on a plantation somewhere. None of them are living with him.

David Blight

He is an orphan, and even though he never used the term, it is a central fact of his life. This is where the loss idea that you brought up comes in; all memoirs are about retrieving loss – our lives are lost somehow but if we write a memoir, we are trying to retrieve and then manipulate our reader at the same time. He has a great deal of loss and a tremendous scarring of his soul, psyche, or mentality – whatever we want to call it. I don’t try to overthink that, but he experienced or saw every kind of savagery and he comes out of slavery with tremendous rage. Since we are talking about literacy and the power of words, his great luck is that he became such a genius with words because he could process that rage into language. If he didn’t do that, what would he do with that rage?

Robert Stepto

We all know how rage can shut people down. But Douglass found an energy and an eloquence in it. I’m glad you made the point about him being an orphan. What goes on in the early pages of that second Narrative is how bereft he is: no family, no home. And finding out that in a year or two he is going to be taken on a twelve-mile walk, where he will become a slave on a plantation. Part of what he tells us in that story is his grandmother’s role in taking him there and then once she is certain that he is playing with his siblings and cousins, she leaves. And indeed, he finds out that she has left when one of the children says, “You know, Granny’s gone.” And with that, he begins the rest of his childhood abandoned, which leads me to think about the family that he and Anna Murray created, five children, and what they were trying to do. One of the things that is gratifying is the whole idea that they created a family and that they were married for forty-four years before she passed away. On the other hand, as you learn about his life story, you realize how little time he spent at home. Some of his speaking tours would take a year and a half or more. So, it is a little disconcerting to think about how he created a family, but he wasn’t there very much.

David Blight

I used to call him the absent father for abandoning his children. And then a friend said that I should not be judgmental; that is what men had to do in the nineteenth century. On the question of the Wye Plantation, there has always been a lot of mystery about whether Douglass was making that up. We know a great deal about what he made up and what was truthful because of a book by Dickson Preston called The Young Frederick Douglass, published in 1980.

The people who now own the Wye Plantation, which is still there – same house, some of the same outbuildings – are the fifth-generation direct descendants of the Lloyds. They have now, finally, embraced Douglass. They are proud of the fact that the most important person from the state of Maryland in American history was a slave on that land. And the kitchen house in which he watches as Aunt Hester is beaten is now a very fancy remodeled apartment, but the fireplace is still there and so is the crawl space next to it where he hid. I have been privileged to stay there twice, sitting in front of the fire. Among the many nature metaphors in his autobiographies – there are water metaphors, fowl metaphors, flower metaphors, and so on – Douglass describes walking around the Wye Plantation when he is seven years old and watching the black birds and imagining himself on their wings. They would always land in the trees and then away they would go, and he would wish he was on their wings.

One morning, very early, I saw thousands of black birds and thought, “He didn’t make that up.” And then there are the sailing ships on the Chesapeake. He didn’t make that up either. Sometimes there is that amazing moment when you realize in literature that some metaphors are not just metaphors. Douglass had an uncanny memory, which was not always accurate, but nobody’s memory is always accurate. One of the things you need to do if you study this person is to understand what do we actually remember from childhood. He engaged in a great deal of effort to reconstruct his childhood and he gets almost every name, place, and timing correct. But the storytelling he puts in it is his own.

Crystal Feimster

I would like to read one last quote that lines up with something that Robert wrote: “Douglass is remembering places and names and, in some fundamental ways, wrestling control of those memories by handling them and in that sense, owning the names of the people who once, in effect, owned him.”

Robert Stepto

A very important feature of his first autobiography is when he mentions names. He names the plantation owners and the overseers, and even describes the evil overseer, Mr. Severe. And then he names Gore, who replaced Severe after he was fired for not being profane.

David, among others, has mentioned that Frederick Douglass was the most photographed American of the nineteenth century and I think there are lots of things to think about why that happened, how that came to be, and why indeed he wanted to be photographed.

© 2019 by Ian Shapiro, Robert Stepto, David Blight, and Crystal Feimster, respectively