Humanities Indicators, a project of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, on Sunday released new data on the career outcomes of graduate degree recipients.

The information, which comes from the National Science Foundation-sponsored National Survey of College Graduates and the Survey of Earned Doctorates, sheds new light on job satisfaction, earnings and first jobs for Ph.D. and terminal master’s degree holders.

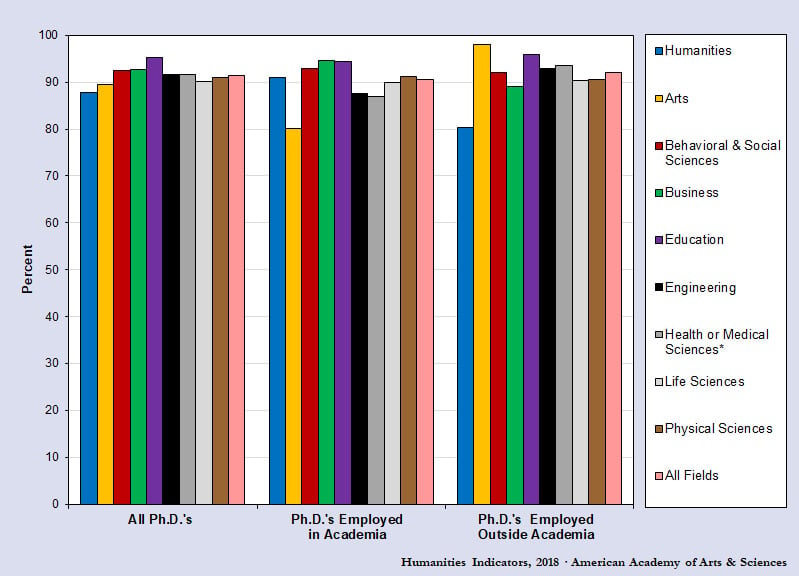

Perhaps most strikingly, humanities Ph.D. recipients in 2015 had relatively high job satisfaction over all: 88 percent said they were “very” or “somewhat” satisfied with their employment. But there was an 11-percentage-point satisfaction gap between humanities Ph.D.s working in academic positions and those working outside academe (91 percent versus 80 percent).

Job Satisfaction Among Ph.D.s (percent)

Robert Townsend, director of the academy’s Washington office, said that was “more than a little disappointing, as someone who believes in the efforts to promote career diversity.” Because of the sample size of the survey, he said, he and colleagues couldn’t isolate the reasons for the gap. Yet it was “all the more striking” because it wasn’t evident among other academic fields. (Townsend reiterated that the data are a snapshot of Ph.D.s employed in 2015, the most recent year for which data were available. And numerous disciplines and institutions have indeed ramped up career diversity initiatives since then.)

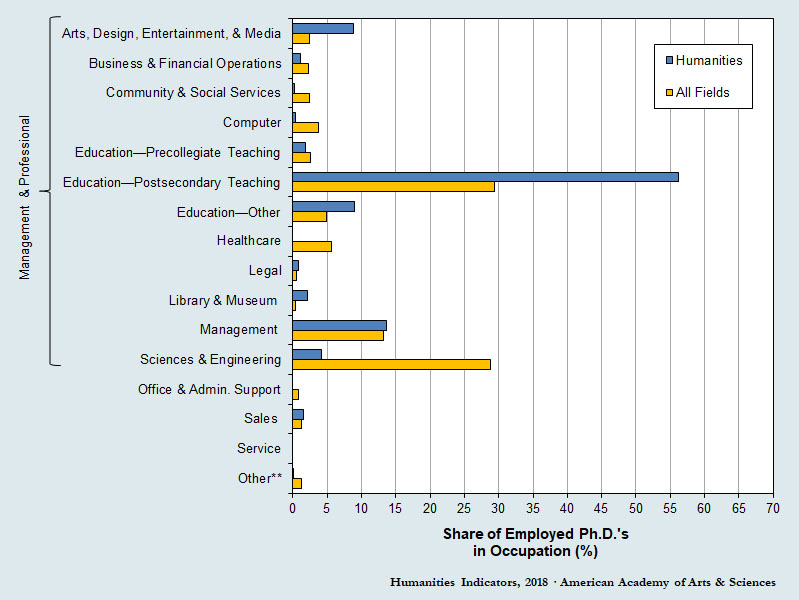

Other key findings include that 56 percent of employed humanities Ph.D.s were teaching at the college or university level as their principal occupations in 2015. By way of comparison, just 29 percent of all Ph.D.s in all fields listed postsecondary teaching as their primary occupation. Of course, many who earn Ph.D.s in the sciences plan all along for jobs in industry.

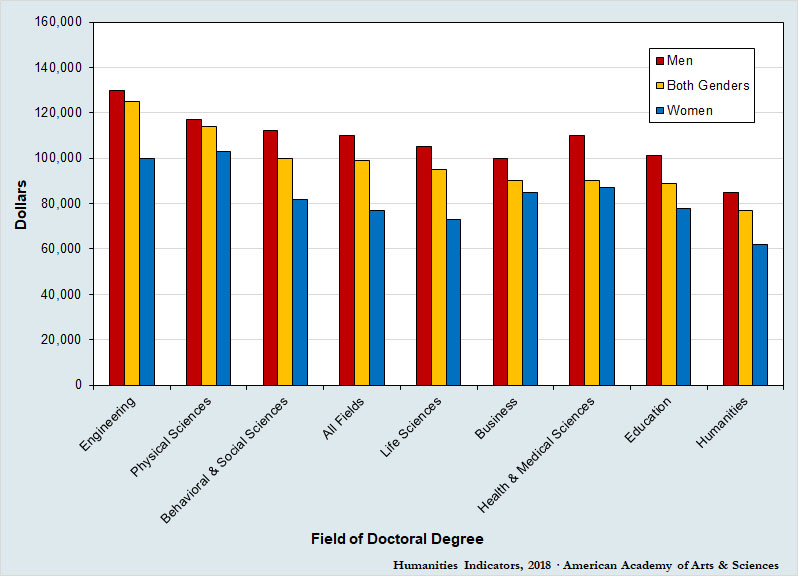

That’s not to say that teaching is particularly lucrative, however. Humanities Ph.D.s reported having the lowest median annual earnings -- $77,000 -- of all Ph.D. recipients surveyed (excluding arts Ph.D.s, whose median income could not be gleaned due to the small sample size). The median income for Ph.D. holders across fields was $99,000.

Annual Earnings Among Ph.D.s

New humanities Ph.D.s were also the least likely to have a definite job or postdoctoral position lined up upon graduation, at 52 percent compared to 62 percent of all new Ph.D.s. That was the lowest level in at least two decades, according to the academy’s analysis.

From 1996 to 2006, the share of new humanities Ph.D.s with a job in hand increased to nearly 60 percent, but the percentage then fell sharply over the next decade, to 41 percent, according to the report. A relatively small but growing share of humanities Ph.D.s went on to postdoctoral studies in 2016 -- 11 percent, up from 4 percent 20 years prior.

New humanities Ph.D.s with definite employment commitments were much more likely to be working in academe than their counterparts in the natural sciences, technology, engineering and math. Some 76 percent of humanities doctoral degree recipients with a commitment in the U.S. said they’d be working in academe, either full- or part-time teaching or administrative positions. In the behavioral and social sciences, the share entering academia in 2016 was 54 percent. Among new engineering Ph.D.s, the share was 14 percent, the smallest proportion among the fields examined.

Where Humanities Ph.D.s Work

Looking at the overall picture for humanities Ph.D.s, Townsend said he remained “fascinated by the disparity” between them and their counterparts in other fields in terms of how many end up teaching.

The data “reinforce the idea that the humanities are unusually focused on academia as a career outcome,” he said, guessing that the lower median earnings reflect that fact. Yet higher job satisfaction levels for humanities Ph.D.s who remain in academe “suggest that less tangible benefits” help compensate, he said.

As for humanists with terminal master’s degree, about 88 percent of workers said they were satisfied in 2015. That was higher than business degree holders but slightly lower (within a few percentage points) than in every other field. Location, opportunities for advancement and contribution to society seemed to account for job satisfaction among these humanists, even if pay and benefits did not.

Among terminal master’s degree holders in the humanities, 37 percent were employed in teaching occupations. Outside of teaching, the largest share of humanities master’s degree recipients, 11 percent, worked in management. Their median full-time income was $58,000. That’s higher than arts and education degree holders but $17,000 below the annual median income for terminal master’s degree holders across fields.