At the 3rd Meeting of the Academy held on August 30,1780, Academy Members voted to appoint “a Committee to confer with the Reverend and Honorable Corporation of the University of Cambridge upon pursuing measures to procure an accurate observation of the Solar eclipse in October next, in the eastern part of this State.” Harvard Professor and Academy member Samuel Williams was put in charge of the expedition and later wrote an account in the first volume of the Academy’s Memoirs (1785):

“It is but seldom that a total eclipse of the sun is seen in any particular place. A favourable opportunity presenting for viewing one of these eclipses on October 27, 1780, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the University at Cambridge, were desirous to have it properly observed in the eastern parts of the State, where, by calculation, it was expected it would be total. With this view they solicited the government of the Commonwealth, that a vessel might be prepared to convey proper observers to Penobscot-Bay [now Maine]; and that application might be made to the officer who commanded the British garrison there, for leave to take a situation convenient for this purpose.

“Though involved in all the calamities and distresses of a severe war, the government discovered all the attention and readiness to promote the cause of science, which could have been expected in the most peaceable and prosperous times; and passed a resolve, directing the Board of War to fit out the Lincoln galley to convey me to Penobscot ....

“We took with us an excellent clock, an astronomical quadrant of 21/2fe et radius..., several telescopes, and such other apparatus as were necessary.”

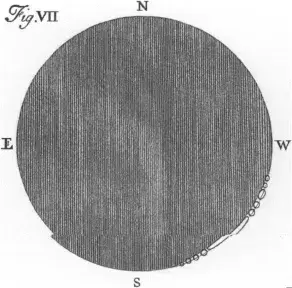

Having obtained permission from the occupying British forces to cross enemy lines, the expedition party nonetheless was unable to reach their intended location in Penobscot Bay. However, setting their instruments instead on present-day Maine’s Long Island allowed them to see and record “beads” of sunlight during the eclipse known as Baily’s Beads, so named for Francis Baily’s 1836 explanation of the phenomenon, the light effect produced during an eclipse by the uneven surface of the moon. Williams’ account includes what probably was the first description of Baily’s beads, some fifty years earlier than Baily. Williams had written: “Immediately after the last observation, the sun’s limb became so small as to appear like a circular thread, or rather like a very fine horn. Both the ends lost their acuteness, and seemed to break off in the form of small drops or stars; some of which were round, and others of an oblong figure. They would separate to a small distance: Some would appear to run together again, and others diminish until they wholly disappeared.” A figure of what the expedition saw was drawn by fellow Member Joseph Willard, in his own account of the event, also appearing in Memoirs.