By Jessica Taylor, Louis W. Cabot Fellow in Humanities Policy at the Academy, and Robert B. Townsend, Director of Humanities, Arts, and Culture Programs at the Academy and Codirector of the Humanities Indicators

The Summer 2022 issue of Dædalus offers a new perspective on an old subject. While the humanities have been around as subjects of study for centuries, a focus on how they engage with and connect to the public outside of academia is relatively new.

Recent research from the American Academy’s Humanities Indicators project tracks the field’s troubles in academia (as measured by degrees awarded and jobs advertised for new faculty members), but also points to the vitality of the humanities among the public (through historical television shows, reading, and visits to museums and literary events). The Dædalus volume takes up this apparent contradiction and explores the relationship between academia and the public from both directions. Essays written from the perspective of academics assess where and how their disciplines are evolving to connect with the public in new ways or address large public problems. Other essays, by leaders in the public humanities, consider how the challenges in the academy relate to their work in local and state programming and museums, as well as efforts to help students enter the workforce.

Given that dual focus, people in the humanities will find much of interest in this collection, but so should anyone who cares about the future of the field or engages with the humanities through museums, books, and other media. The seventeen essays explore the relationship between the public and the humanities in three ways. First, some essays offer the latest research on where, how, and why the public thinks about and engages with the humanities in a variety of forms. Second, other essays gather examples from some of the most interesting and engaging public-facing projects in the humanities. This ranges from the work of the state humanities councils to projects on both coasts working with and for underserved communities to preserve and share their stories. And the third way is more conceptual, with leaders in emerging areas of the field (such as the medical, environmental, and Positive Humanities) describing developments that can open new forms of public engagement with the humanities.

Throughout the volume the authors wrestle with recurring perceptions of a “crisis” in the humanities. Judith Butler (Academy member and Distinguished Professor, University of California, Berkeley) states that “If there is a single hope that any of us can have for the future of the humanities, it is that the public humanities become a way to assert the public value of the humanities.” But she also warns about the risks of aligning uncritically with structures and institutions that have undermined public attitudes about the field. On the other hand, Carin Berkowitz and Matthew Gibson (Executive Directors of the New Jersey and Virginia humanities councils, respectively) argue for a more positive vision of that engagement, calling for “a humanities of new expressions of culture and of new understandings derived from shared perspectives . . . to address the divisions and disconnectedness so common in contemporary America.”

The analytical essays offer a statistical perspective on the relationship between the humanities and the public, drawing on recent research from the Humanities Indicators about the public and academia as well as a new analysis of a massive corpus of social media and news publications. Notably, the latter study finds that the humanities appear often in the media, but in ways that differ substantially from the sciences (which are much more likely to be noted for new discoveries, while the humanities tend to come up in more mundane contexts – ranging from event announcements to obituaries). The research team on the WhatEvery1Says project concludes that “In order for the humanities to engage with grand challenges, a chain of linkages from their discrete practices to more general values needs to be established and communicated.”

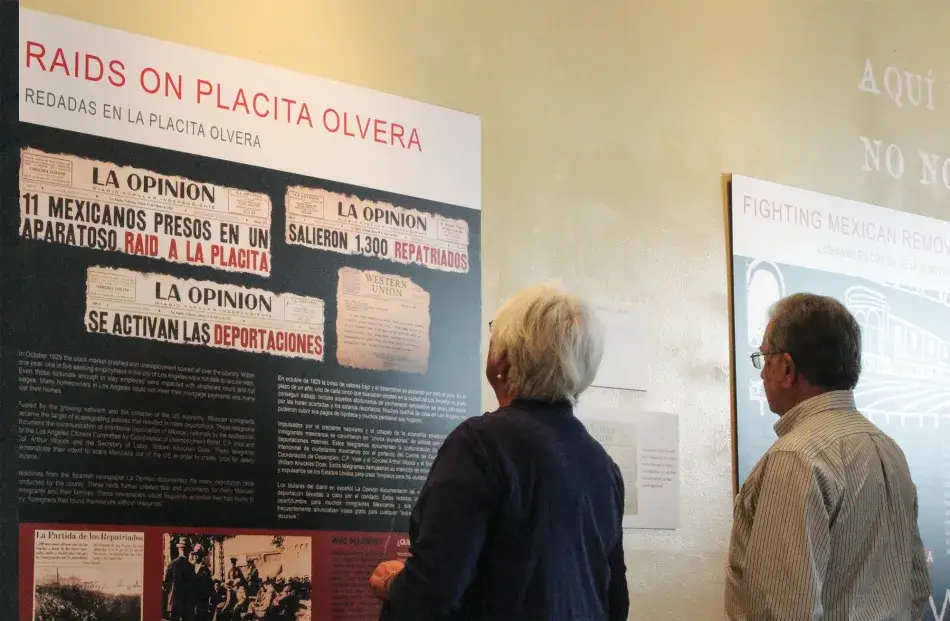

The efforts to create these chains of linkages are the subject of most of the essays in the volume. In contributions by George Sánchez (Professor of American Studies & Ethnicity and History, University of Southern California) and Denise Meringolo (Associate Professor of History and Director of Public History, University of Maryland, Baltimore County), for instance, the connections are built with and in relation to members of their communities. Sánchez describes efforts with his students to create a museum for the Boyle Heights neighborhood in Los Angeles, while Meringolo summarizes her collaborative work to capture and present the stories of communities in Baltimore following the death of Freddie Gray in police custody.

Other authors describe efforts to construct the linkages by rebuilding and opening their disciplines to the evolving interests and concerns of the public at large. Kwame Anthony Appiah (Academy member and Professor of Philosophy and Law, New York University) reimagines how philosophy can reorient public thinking about evolving questions of justice, while Keith Wailoo (Academy member and Professor of History and Public Affairs, Princeton University) traces the emergence of the medical humanities from an aspirational goal to a pandemic necessity. And in an essay on the new area of research called the Positive Humanities, James Pawelski (Professor of Practice and Director of Education, Positive Psychology Center, University of Pennsylvania) calls on humanities scholars to recognize the psychological benefits that engagement with the humanities can have to promote human flourishing. Collectively, these essays attest to Appiah’s assertion that, “We need not the sure path of one science, but a difficult conversation among all the different kinds of systematic knowledge. We need it because people need it, and all the disciplines of the humanities have something to contribute.”

While the authors approach the question from a variety of perspectives, together they demonstrate that the humanities are actively engaging with the public and their concerns. Though it remains to be seen whether these efforts will have an effect on the troubling trends in the academic humanities, the Dædalus issue bears witness to a field rising to the challenges of today.

The issue was coedited by Carin Berkowitz, Norman Bradburn (Academy member and Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus and Senior Fellow at NORC at the University of Chicago), and Robert B. Townsend (Director of Humanities, Arts, and Culture Programs at the American Academy).

The Summer 2022 issue of Dædalus on “The Humanities in American Life: Transforming the Relationship with the Public” features the following essays:

Planetary Humanities: Straddling the Decolonial/Postcolonial Divide

Dipesh Chakrabarty

“The Humanities in American Life: Transforming the Relationship with the Public” is available on the Academy’s website. Dædalus is an open access publication.