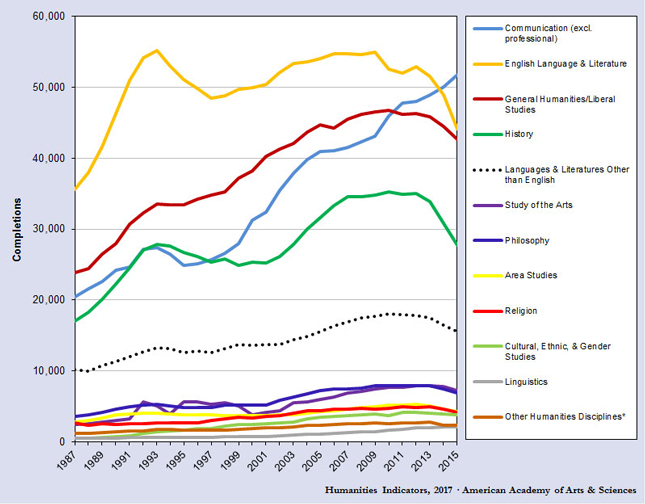

In a new release today, the Humanities Indicators reports on substantial declines in the number of bachelor’s degrees conferred in the field (marked by a 9.5% drop in the total number of humanities degrees conferred from 2012 to 2015). The decline would look slightly worse if not for a technical adjustment in the mix of disciplines counted as the humanities. The Indicators staff added areas of the communication discipline that fall within the humanities to the time series. As the figure below shows, even when the pre-professional areas of communication are excluded, the number of degrees awarded in that discipline increased substantially even as the other humanities disciplines have seen sharp declines in the number of undergraduate degrees.

Number of Humanities Bachelor’s Degree Completions, by Discipline, 1987–2015

With the change this year, the Indicators staff and Advisory Committee believe the data series now provides a more complete picture of the humanities enterprise. Trevor Parry-Giles (director of academic and professional affairs at the National Communication Association and a professor at the University of Maryland) explains the case for change.

Communication as Humanities, Humanities as Communication

Trevor Parry-Giles

In November 1914, on an unseasonably warm Chicago day, 17 speech teachers voted to formally sever ties with the National Council of Teachers of English and form their own association, the National Association of Academic Teachers of Public Speaking (now the National Communication Association). In so doing, these teachers declared that the study and teaching of communication was distinct from other disciplines, deserving of its own institutional and intellectual legitimacy as a discipline within the context of American higher education. Communication is now firmly established as a course of both undergraduate and graduate study in colleges and universities across the United States and around the world. As our world and our society become increasingly communicative, students and their parents are, in ever growing numbers, finding communication an attractive major. They realize that, at its foundation, communication focuses on how people use messages to generate meanings within and across various contexts, and is the discipline that studies all forms, modes, media, and consequences of communication through humanistic, social scientific, and aesthetic inquiry.

The academic study of communication dates back centuries. For the ancients, communication was the study of rhetoric—the art of persuading others through public speaking and oratory; they believed that understanding rhetoric was critical for every citizen’s education. As the ancient Greek rhetorician Isocrates declared in Antidosis, “Because there has been implanted in us the power to persuade each other and to make clear to each other whatever we desire, not only have we escaped the life of wild beasts, but we have come together and founded cities and made laws and invented arts; and, generally speaking, there is no institution devised by man which the power of speech has not helped us to establish.”

The classical study of rhetoric as a liberal art in European colleges and universities migrated to the U.S.; Harvard University has long had an endowed chair in rhetoric and oratory (the Boylston Chair), for example, and one of the first professors in that position, John Quincy Adams, authored a two-volume collection of Lectures on Rhetoric and Oratory in 1810. The development of the communication discipline in the United States owes much to this classical tradition. Indeed, as NCA President J. Jeffery Auer revealed in his 1965 congressional testimony concerning the establishment of the National Humanities Foundation (now the NEH), “And the study of rhetoric has been a part of the Western humanistic tradition, almost unbroken in liberal education since the day of Aristotle. It was central to classical Greek education, and it continued to be so in the Roman schools when Cicero—probably the first man to speak of the ‘liberal arts’—adapted from the Greeks his own ideas of education.” It was this intellectual heritage that moved Professor Auer to remind Congress that “speech (communication) is one of the humanities.”

Communication is, as an academic major, remarkably diverse, encompassing traditional tracks in rhetorical theory and criticism alongside pre-professional programs in public relations and journalism. At their core, however, communication scholars and teachers retain their appreciation for the role and influence of communication across all aspects of public and private life. They continue to embrace the ubiquity of communication and are mindful of the inherent value of communication to meaningful citizenship. Emerging from the democratic impulse embodied in 19th- and 20th-century progressivism, this is the pedagogical foundation of the discipline from which all the diverse contemporary manifestations arise. Communication cuts across contexts and situations; it is the relational and collaborative force that strategically constructs the social world. Knowledge and understanding of communication and strong communication skills allow people to create and maintain interpersonal relationships; employers in all sectors seek employees with strong communication skills and knowledge; and society needs effective communicators to support productive civic activity in communities.