Arms trafficking has a long and influential history. At an Academy event held in Berkeley, California, historian Brian DeLay described how U.S. arms trafficking intervened at critical moments to destabilize Mexican governance. The program, hosted by the Berkeley Local Program Committee and moderated by David Hollinger, included commentary from historians Priya Satia and Daniel Sargent, as well as from political scientist Ron Hassner. The presentations explored how the history of arms trading may help to better understand the history of state-making and the power relations between the United States and the rest of the world. Edited transcripts of the presentations follow.

2087th Stated Meeting | November 20, 2019 | University of California, Berkeley | Morton L. Mandel Public Lecture

Brian DeLay is Associate Professor of History at the University of California, Berkeley. His publications include the award-winning book War of a Thousand Deserts: Indian Raids and the U.S.-Mexican War and the monograph Aim at Empire: Arms Trading and the Fates of American Revolutions.

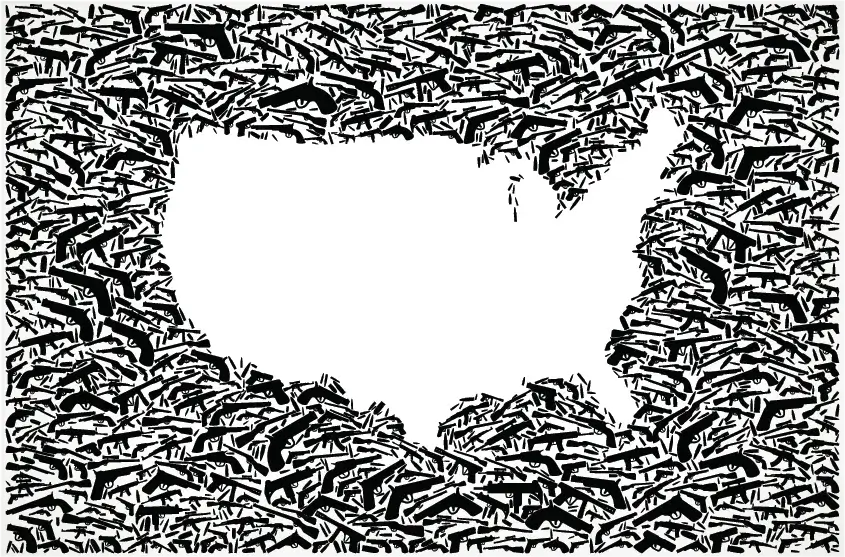

I am going to begin with something that will not surprise you: the United States is the arsenal to the world. I had initially planned on speaking about U.S. arms trading over the long term, and I wanted to root that discussion in a broader conversation about the connection between the U.S. government and the private arms industry, which has been present and essential to the American arms industry since the Revolution. Part of the reason I thought that would be interesting is that the gun lobby has invested enormous resources in convincing the public that the government is the enemy of the arms business instead of its historic and indispensable patron. But as I began to plan this talk, I kept seeing disturbing news from Mexico that was very relevant to tonight’s topic. For example, a month ago a military unit from the Sinaloa cartel used .50 caliber M2 machine guns and other military-grade weapons to free the son of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, the jailed Mexican kingpin, from state custody, a profoundly humiliating and disturbing event for the Mexican government. The weapons they used almost certainly came from the United States.

Two weeks ago, cartel hitmen murdered three women and six children from a single Mormon family. The cartel hitmen left behind hundreds of shell casings made by Remington, a U.S. arms manufacturer. Asked about the role of U.S. arms trafficking in these awful events, an official with the ATF (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives) said, “This is an ongoing problem. It’s been with us for a while.”

As a nineteenth-century historian I can attest to that fact. With the possible exception of Haiti, Mexico has had a longer and more destabilizing relationship with American guns than any country in the world. There’s an old saying in Mexico, “Poor Mexico, so far from God, so close to the United States.” The country’s two-thousand-mile-long land border with the hemisphere’s preeminent arms manufacturer and exporter has hardwired instability into Mexican history. In my brief remarks this evening, I hope to convince you of this state of affairs by taking you on a very quick tour through Mexico’s nineteenth-century history and explaining how U.S. arms trafficking intervened at critical moments in that history to destabilize Mexican governance.

Before I get to that history, let me say something about how the buyers in this story acquired the weapons that they used to pursue their political projects. One method was to pay outright with gold or silver, or with bills, cotton, horses, and sometimes slaves. Others, particularly governing elites and well-connected purchasers looking to buy in bulk, paid with bonds, with loans, or with vaguer kinds of promises about what they would do once they took power. Political scientist Michael Ross, a specialist in conflict in post–Cold War Africa, refers to the market for such promises as “booty futures.” He notes that this is a particularly destabilizing kind of finance precisely because it empowers the weak and the disconnected to do things that they otherwise would not have the power to do and probably wouldn’t even try if they didn’t have that support. Booty futures figure prominently into the story that I’m going to share with you tonight. Finally, a warning. Mexico’s misfortunes in the nineteenth century were so profound and so numerous as to almost defy belief. But I promise I am not making any of this up. In fact, I’m actually leaving out many traumatic things that happened in nineteenth-century Mexico.

Let’s begin with the Mexican War of Independence. This was a longer, bloodier, far more destructive war than the American Revolution. It lasted from 1810 until 1821. Among many other places in what had been New Spain and what was going to become the independent republic of Mexico, the war had devastating consequences for the underpopulated province of Texas. Mexican insurgents struggled to capture seaports and therefore understood that their best chance of arming the insurgency was to acquire a border with the United States. So there was fierce fighting over the land border between Texas and Louisiana. Crown officials, not wanting to see this happen, invested significant resources in stopping that project, causing Texas to be torn to pieces during those ten years. Its already small population was cut almost in half and its animal wealth, which was really the main economic enterprise in Texas at the time, all but collapsed.

Now the reason this is an important story to share, first of all, is just as a measure of the antiquity of the U.S. arms trafficking problem and the U.S.-Mexican relationship. But, more importantly, the story is relevant because the devastation in Texas from 1810 to 1821 prompts the new independent republic, once Mexico achieves independence in 1821, to make a very critical decision. It decides that in order to hold onto this territory it has to populate it, and that the most efficient way to do that is to invite Anglo-American settlers from the United States into Texas.

Now, at the same time that the government made that fateful decision it was trying to figure out how to arm and defend itself as an independent postcolonial state. Mass-producing arms domestically was too complex and expensive, so that was not an option–certainly not in the short term and not even by the early twentieth century. It was just too difficult, partly because the technological horizon in the nineteenth century was racing forward too quickly for Mexico to ever catch up. Broke and exhausted from its long war for independence, Mexico lacked the cash necessary to buy new arms on the open market from one of the major global producers at the time. So, in the mid-1820s, Mexico secures two major loans from prominent banks in London that are guaranteed by two-thirds of all the country’s customs receipts, which were really its only reliable source of income at that moment. Almost all of these loans are converted immediately into used war material, things left over from the Napoleonic wars, such as four frigates, five thousand pistols, four thousand carbines, and seventy thousand East India Pattern “Brown Bess” muskets.

This was supposed to be the beginning of a prolonged arms campaign that would gradually build up state capacity over the coming decades. But the Mexican government would not secure another arms deal this large for the rest of the century. Just three years after making the deal with these London banks, Mexico defaults on its payments. Mexico would in fact spend the next sixty years in sovereign default, more or less barred from international capital markets and in a very unstable condition. Because it was barred from international capital markets and because it didn’t have adequate revenue, Mexico is unable to finance even the basic tasks of central government, causing it to be terrifically unstable over the course of most of the nineteenth century. I’ll give you just one metric. In the thirty-five years between 1821 and 1856, Mexico had fifty-three separate governments operating under four different constitutional systems. So just an absolute churn of political turmoil.

For a generation Mexico’s leaders would face one crisis after another with an already outmoded and dwindling arsenal. The inadequacy of that arsenal was tested in the mid-1830s in Texas. Here we get back to those Texans I was talking about a moment ago. Over the previous fifteen years, the Anglo-American colonists and African slaves Mexico had invited into Texas arrived in greater numbers than Mexico had anticipated and in far greater numbers than Mexico even wanted. Indeed, in 1830, in a panic, Mexico criminalizes further immigration from the United States into Mexico. Unsurprisingly American immigrants ignore this prohibition and Anglo-American “illegals” continue to come into Mexico, bringing enslaved men, women, and children with them in contravention of Mexican law. In 1835, the colonists rebel against the central government.

Now, rebellions had happened in Mexico before. Other larger, more powerful states had rebelled against the central government and in each case the central government had handily put down the rebellion. So why did the Texans think that they could do better? They were confident, but that doesn’t really explain it. They didn’t have the number of men, the weapons, or the money that the state of Zacatecas had, for example. And Zacatecas’s rebellion was completely crushed by the central government. So why did Texas think it could succeed? Well, Texas had two advantages that Zacatecas did not. It shared a land border with the United States, and it had an increasingly precious booty future, namely, cotton land. The Texan authorities pursued desperate land for arms deals. The most consequential were deals made in New Orleans by Texas agents who had been authorized to offer up to one and a quarter million acres of prime cotton land in exchange for war material. To defeat the Mexican army in 1836, the Texans relied on the arms, ammunition, and even some men from Louisiana.

While this was unfolding, arms trafficking was helping to produce yet another catastrophe in northern Mexico. Mexico had title to a sprawling northern territory, what’s now the American West, but at the time most of that territory was controlled by indigenous polities. For complex reasons, the uneasy peace that Mexico had enjoyed with the Comanches, Apaches, Kiowas, Navajos, and other native peoples collapses in the 1830s. Armed with guns and ammunition obtained from other native people who themselves had obtained them from American agents or American merchants, mounted indigenous warriors began launching raiding campaigns across the whole of northern Mexico. Over the next decade these campaigns claimed thousands of Mexican and native lives, depopulated vast swaths of northern Mexico, and wrecked the ranching economy that was the mainstay for the entire north of the country. Raiders paid for their guns with stolen mules, stolen horses, and Mexican captives. They were able to traverse nine Mexican states because almost always they were far better armed than the Mexicans they encountered.

Mexico’s harried government by the late 1830s and early 1840s promised to conquer los indios bárbaros, as they called these raiders, and to reconquer Texas. These were empty promises. Mexico’s army was in terrible shape by the mid-1840s, with a dwindling number of outmoded guns, about thirty-three thousand according to the minister of war. They had some 635 cannons of various calibers, most of which dated from the colonial period. The fact that this arsenal was unequal to the national task became agonizingly clear in 1846 when the United States invaded Mexico and provoked the Mexican-American War. After every successful battle the far better armed U.S. forces seized and destroyed the weapons they captured from their defeated Mexican adversaries. After his victory at the Battle of Cerro Gordo, for example, General Winfield Scott determined that the four thousand muskets seized from the conquered Mexican army that day were all far too substandard for his men to use. So he had the muskets destroyed.

Some in Mexico wanted to continue fighting the United States even after Mexico City itself was occupied by U.S. troops, but it’s not at all clear how the state could have possibly waged that war. In the spring of 1848, Mexico’s shocked minister of war reported that government stores contained only 48 functioning cannons and a mere 121 muskets for the whole country. The United States insisted that Mexico surrender more than half of its national territory as a precondition for ending the war. Here is the great cataclysm of nineteenth-century Mexican history. In 1848, at the conclusion of the Mexican-American War, Mexico was not only less than half the size it had been when it achieved independence, but it was internally fractured, it was groaning under vast internal and international debts, and it was as gun-poor as it had ever been in its postcolonial history. But this state of affairs was not going to last very long. Just several years after its war with the United States, Mexico plunged into a destructive civil war between liberals and conservatives known as the War of Reform.

In early 1861, only months after the War of Reform comes to an end, Mexico was once again invaded by a powerful foreign enemy. Seizing on Mexico’s unpaid debts and the fact that the United States was distracted by its own civil war, France invaded Mexico in 1861 and soon thereafter installed a European prince as Emperor Maximilian the First. Mexico’s liberal government, led by Benito Juárez, steadily lost ground and in 1865 Juárez fled to Texas. Now, the one good thing about being driven out of your country and being forced into Texas is that you are in close proximity to a lot of guns. Juárez followed a pattern that by then had become well established. He sent agents out to dozens of American cities and helped them sell millions of dollars’ worth of Mexican government bonds at desperately discounted prices. The agents found very prominent buyers. The list of Mexico’s erstwhile patrons in 1865 and 1866 reads like a who’s who of America’s incipient gilded age. It included J.P. Morgan, William Aspinwall, Anson Phelps, Moses Taylor, and the country’s most powerful arms dealer, Marcellus Hartley.

These investors provided the money and the material necessary to equip the liberal reconquest of Mexico. The bill for all of these loans and this material started coming due in 1867 as soon as Juárez and his forces took Mexico City, captured Maximilian, and then executed him. The bond holders, in New York City primarily, hatched a multitude of business schemes in Mexico over the following months. And I think this was in fact the purpose of scooping up all of these discounted Mexican bonds to begin with. Mexico had absolutely earned its reputation for financial insolvency. The idea that these savvy, extremely powerful capitalists would buy these bonds expecting prompt repayment was absurd. They bought these bonds because they knew that doing so would give them leverage over things that they regarded as far more important and promising in Mexico. This included things such as land deals, mining concessions, commercial privileges, and above all by the mid-1860s and early 1870s, railroad contracts, where the real money was. Juárez did a fair job trying to hold these creditors at bay, until his death in 1872.

Thereafter, pressure mounted on his ally and successor, Sebastián Lerdo. Like Juárez, Lerdo was a proud nationalist. He did not have the means to pay back these bonds, not in the time scale that the creditors demanded, and he certainly had no intention of handing U.S. creditors the economic keys of the kingdom. In 1875, after beating his rival Porfirio Díaz in that year’s presidential election, Lerdo canceled all of the contracts for outstanding U.S. railroads. He also rejected a bilateral trade agreement that had been seen by these creditors as their last best hope of ever getting their money back. In 1876 the bondholders conspired with their stymied colleagues in the railroad business to help Díaz depose Lerdo in a coup. The bondholders sent Díaz $320,000 in cash through an intermediary, and arms and ammunition soon began arriving in bulk at the Texas border, where Díaz was waiting. Thus equipped, Díaz deposed Lerdo and soon won election to the presidency. Relying on these foreign partners and others whom he cultivated as well as on massive amounts of foreign investments, Díaz would go on to build an effective and extremely well-armed dictatorship. He would control the country for about thirty-three years.

There is a crooked but unbroken line between Mexico’s frantic scramble for arms in the 1850s and the 1860s on one hand, and the rise of Díaz’s dictatorship on the other. Coups were nothing new in Mexico by this time, but the direct and the decisive influence of American capital in toppling an elected government abroad: that was novel. As Juárez and Lerdo well understood, all they needed were the investments that gave American businessmen the sense of entitlement necessary to intervene in foreign governance. In Mexico’s case, those investments had their modest but indispensable beginnings with the arms trade.

Díaz transformed Mexico. His rule was marked by rapid development, savage inequality, and foreign ownership of broad swaths of the economy. He cooperated with the United States to do something that governments, Mexican governments in particular, had failed to do for decades: conquer the Comanches, the Apaches, the Yaquis, and other powerful native people who had defied state power for so long. These conquests paved the way for unprecedented economic investment in the borderlands. Díaz finally fell from power during the Mexican revolution in 1910, a revolution equipped with arms from the United States. In other words, his very success helped lay the groundwork for his eventual overthrow.

With native people conquered, merchants in Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California now had the capital, the connections, and the transportation infrastructure necessary to channel war material from its production sites in eastern North America, including Connecticut and upstate New York, to borderland buyers in virtually unlimited quantities. Moreover, the proliferation of huge mining, ranching, and agricultural enterprises south of the border, almost all of them American owned, gave revolutionaries like Pancho Villa abundant targets from whom to extort or plunder cash, crops, and cattle–things that could be traded for war material just north of the border. Even today the most recognizable icon of the Mexican Revolution is a fighting man or woman dressed in American-made ammunition. Throughout the 1910s, American arms and ammunition poured into Mexico in unprecedented quantities. For enterprising merchants in the Southwest it was the great bonanza of their lifetimes. They supplied all comers with war material of every description.

One of the most notorious examples of this nondiscriminatory ethic came from the huge El Paso arms and hardware firm, Krakauer Zork & Moye. The firm once sold the federales one thousand kilometers of barbed wire and then immediately turned around and offered their rivals, the constitutionalists, all the wire cutters that they had in stock. Arms trafficking attracted citizens of prominence as well as merchants. In 1911, Laredo’s former mayor, Amador Sánchez, got caught using the county jail as a depot for weapons destined to be smuggled into revolutionary Mexico. Why did Sánchez have access to the jail? Well, in addition to being president of the Webb County School Board, he was also the county sheriff. He later received a presidential pardon for his violation of U.S. neutrality laws and kept both of his jobs.

The Mexican Revolution was an incredible business opportunity for arms dealers across the borderlands. When it finally grinds to a halt around 1920, it left absolute wreckage in its wake. More than one million people died because of war-related casualties in that decade. Gun violence, of course, continues at lower levels in Mexico when the war ends. But it has once again become a massive crisis over the past several years. We are living in a time when U.S. arms trafficking is again posing a first-order problem for the Mexican state. Let me close with a few words about how this nineteenth-century scourge has returned to afflict Mexico in the twenty-first century.

The violence that is affecting so much of Mexico really starts in 2006. Following a disputed election, Mexico’s newly installed president, Felipe Calderón, declared war on his country’s drug cartels and deployed the army against them in several sites around the country. The pressure that the Mexican state brought to bear sparked an intense and vicious competition between cartels for territory and for transportation routes into the United States. Gun violence soared across much of the country despite the fact that it is legally very difficult to purchase firearms in Mexico. In the entire country there is a single store where civilians may purchase firearms, and the army decides who can and cannot shop there. Nonetheless, guns are not difficult to acquire in Mexico. The large majority of them are smuggled in from the United States. By 2012, there were some 6,700 licensed U.S. arms dealers in the border region. That’s more than three licensed arms dealers for every mile of the U.S.-Mexican border. A recent study suggests that straw buyers, people who ostensibly buy for themselves but are in fact doing so for others, shopping at these borderlands arms stores and elsewhere in the country purchased about a quarter million guns in 2012 alone to smuggle into Mexico.

The media doesn’t pay nearly enough attention to this phenomenon, but when it does it usually concentrates on the guns alone. And yet ammunition is at least as important, and it is far less regulated than guns are. Because ammunition is not a permanent commodity like guns, it is all the more critical that it be obtained in bulk, which is easy enough to do in the United States. By the end of Calderón’s term in 2012, his drug war had gone spectacularly wrong. Understandably, he wanted others with whom he could share the blame. He identified plausible villains in the U.S. arms industry and in the United States who had not done nearly enough to regulate the arms trade. Calderón went to Ciudad Juárez, which was probably the most dangerous place on Earth by 2012, and used three tons of confiscated American guns to make a massive sign that read, “No More Weapons!” He erected the sign near a bridge connecting El Paso to Ciudad Juárez. It was a stark protest against the so-called “iron river of guns” flowing from the United States into Mexico.

Juárez’s mayor never liked the sign. Perhaps he thought it was bad for tourism, or maybe he thought that the message had already been well received. So he removed the sign. But the problem has only deepened in the years since the sign was taken down. In 2018, Mexico’s homicide rate set an all-time record, surpassing the previous high reached in 2017. And 2019 is on pace to surpass 2018. Gun violence accounts for about 70 percent of all the homicides in Mexico today, and the country’s national security minister recently stated that on average two thousand guns go illegally across the border into Mexico every day to fuel this violence. If he’s right, that would be about three times as many guns as the figure I cited just a few moments ago.

So I think the “No More Weapons!” sign needs to go back up. Versions of it should be placed at every crossing point along the border, all two thousand miles of it. Too few Americans realize how consequential U.S. gun laws are for Mexico and for Mexicans. When we allowed our national assault weapons ban to expire in 2004, gun violence increased in northern Mexico. Lax regulation of ammunition purchases in many states, in particular Arizona, makes it too easy for cartels to buy in bulk and smuggle in what they need. The gun lobby with their Republican allies in Congress have hobbled the ATF in ways that have significant implications for Mexico. And the so-called gun show loophole in this country that permits gun sales without background checks facilitates straw purchases that fuel cartel violence.

In other words, Calderón’s plaintive sign captures a basic fact that is as true today as it was in the nineteenth century: The people with most leverage over the problem of arms smuggling into Mexico read English.

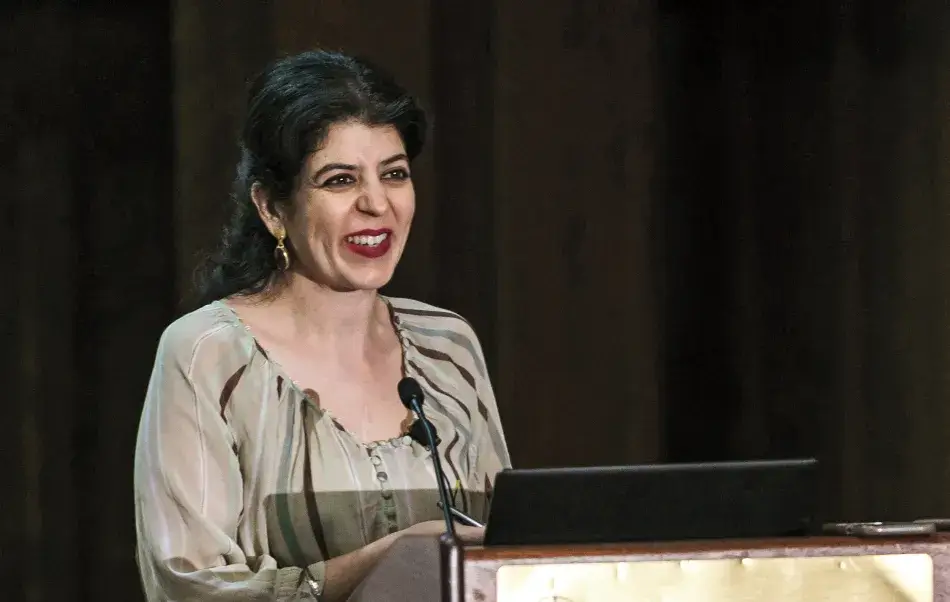

Priya Satia is Professor of British History and the Raymond A. Spruance Professor of International History at Stanford University. Her publications include Spies in Arabia: The Great War and the Cultural Foundations of Britain’s Covert Empire in the Middle East and Empire of Guns: The Violent Making of the Industrial Revolution.

Commentary

The word “trafficking” can mean simply trade, but typically it implies an illegal trade. My remarks will broadly address the past and present of the trade, focusing on small arms, particularly firearms. And I will also reflect briefly on the distinction between trafficking and trade with reference to the future.

When firearms became central to warfare, governments faced a structural problem: they needed the gun manufacturers, but only intermittently. But allowing gun makers to compensate for that uneven government demand by selling arms to civilians was often dangerous. For instance, in early modern England, it was a time of dynastic and religious conflict, and firearms in civilian hands seemed a recipe for civil war. In order to support gun makers in peacetime so that they would still be around in wartime, the British government encouraged gun makers to sell their guns abroad. So, guns wound up enabling the extraordinary expansion of the British Empire in the eighteenth century – as commodities, a currency, and powerful symbols and actual weapons for opening up markets and seizing land, including in North America. Arms sales also fueled the slave trade. Guns were sold to Native Americans and settlers in North America. They were gifted to Native Americans and to South Asian polities as part of the diplomacy of conquest. These sales and gifts were considered essential to British prestige and influence in those regions–and essential to smothering the threat posed by indigenous arms-making.

The East India Company was the main agent of British expansion in the Indian subcontinent, and it was itself a mass-purchaser of firearms. As Brian mentioned, many of the guns that wound up in Mexico were East India Pattern Brown Besses. They were the most massively produced arms of the period. All these sales in the interest of empire helped drive industrialization in Britain. At times British officials, predictably, expressed concern that they might be arming their own enemies abroad, but such concerns were inevitably appeased with the argument that if they didn’t do so they would be forfeiting profit, prestige, and influence because those buyers would simply turn to the French or another rival. Or, perhaps even worse, they might make their own arms. Moreover, by selling the firearms themselves, at least the British would know what kind of arsenal their opponents had.

Powerful anticolonial movements began to emerge by the middle and late nineteenth century around the world, and the appeal of that logic started to wane. By the late nineteenth century, British officials were belatedly struggling to limit arms possession among the Irish, Indians, Afghans, the Maori, black South Africans, and other groups they ruled. The efforts of these groups to obtain arms in defiance of those British restrictions gave rise to that moralizing language of arms “trafficking.” It was about a colonial concern with the wrong people getting arms, not about arms themselves being an immoral good (as in the sense of “human” or “drug” trafficking).

Despite these restrictions on colonial rebels buying guns, European arms sales continued to thrive. European and American arms companies often partnered with banks by the late nineteenth century, and those banks would give loans to client states, leading people to criticize the ensuing arms race. These arms companies, in response, would remind the concerned critics that their arms factories were essential to industry, that their profits accrued to vast bodies of shareholders and employees. In 1935, a British Royal Commission affirmed the reality of very wide public investment in the arms industry despite the growing criticism of arms makers as uniquely villainous “merchants of death” following World War I.

The modern world that we have inherited was and continues to be shaped by this history of arms sales. Like the British in the eighteenth century, the U.S. government today uses arms sales abroad and at home as part of what we now call the military-industrial complex. Though a long global effort to regulate global firearms sales has culminated in the Arms Trade Treaty of 2014, instead of ratifying it the Trump administration is trying to ease controls on firearm exports by moving their oversight from the State Department to the Commerce Department, where some sales may not even require licensing. American arms are on all sides of the conflicts in Afghanistan and Syria. The Islamic State has American arms. Complicity in these sales, as in eighteenth-century Britain, remains wide. Ordinary people like us participate through our tax support, and we benefit through investment, employment, and so on. Even the art world thrives from donations from gun makers.

The firearms industry is, of course, part of a wider arms industry whose global sales are similarly brokered by governments in the name of jobs and security, including for instance the Trump administration’s controversial arms sales to Saudi Arabia despite their role in devastating Yemen and the Saudi government’s abuses of its own citizens. A revolving door between defense agencies and arms firms facilitates this military-industrial complex. Even Silicon Valley owes its rise to defense contracts, which remain important today. Meanwhile strict gun laws in other countries have made American civilians the single most important market in the world for firearms manufacturers. America has always had gun control historically, but the NRA peddles the myth that America is built on the idea of unregulated gun ownership, and it does this in order to protect access to this civilian market. As a result, American civilians now own nearly half the firearms that exist in the world. The American government and governments around the world have an interest in keeping this civilian market open to support an industry understood as essential to security.

Those concerned about this trafficking and its violent effects tend to focus on the villainy of the NRA and the politicians in its pocket, but complicity in arms trafficking is much wider. And that collective investment in a way of life built on arms sales is sustained by the idea that security depends on a mutually terrorized public and a mutually terrorized world. This idea has sustained ties between war and industrial capitalism since the eighteenth century. But the same period has also given us alternative visions of social organization that question whether industrial capitalism, with all its human and environmental wreckage, is really a kind of inescapable default. Arms makers themselves at times suffer from bad conscience. Perhaps the most famous example of this for those of us who live locally is Sarah Winchester, who was haunted by the ghosts of those killed by the Winchester rifle. Bad conscience drove her to build a crazy mansion, the Winchester Mystery House, in the heart of what is now Silicon Valley. But she went on with arms manufacturing, partly just to pay for the construction of this unending project.

Is it possible to reckon more practically with this military-industrial system in which we are all complicit? The gun control movement is pressuring companies to disengage from the firearms industry, and it’s true that sustained activism can produce cultural change–in the same manner that the NRA’s activism has produced a cultural change. As Brian has brilliantly argued in his work, our taxpaying power can be leveraged in decisions about local, state, and federal arms contracts. And then there is the manufacturing capacity of arms makers themselves. Eighteenth-century gun makers coped with uneven government demand by selling guns abroad, but they also coped with uneven demand by diversifying their products. They made things like buckles, harpoons, and swords. Nineteenth-century gun makers produced bicycles, typewriters, and razor blades.

Today’s arms makers might also turn swords into ploughshares, and as we face environmental devastation ploughshares are probably more crucial to security than arms. They might, in short, contract for welfare rather than warfare. In 1807, the British government abolished the slave trade despite many vested interests in it out of a sense that humans were not a morally defensible “commodity.” Some goods should simply not be sold. And this is why the word tra∑cking creates a false distinction when it comes to arms, in distinguishing between legal and illegal arms trades. It’s not the legality that matters, but whether the commodity in question is morally defensible given the political, economic, and existential stakes.

Ron Hassner is the Chancellor’s Professor of Political Science, the Helen Diller Family Chair in Israel Studies, and a faculty director at the Berkeley Institute for Jewish Law and Israel Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. His publications include Religion on the Battlefield and War on Sacred Grounds.

For international relations scholars, and I count myself as one, weapons are a primary concern because we view power first and foremost in terms of military force. There is a significant corpus on the production and sale of weapons of mass destruction or large weapons platforms, submarines, aircraft carriers, missile systems, jets, helicopters, and the like, but there is almost no literature, let alone theory, on arms trafficking. The few articles that are in circulation are very weakly cited and appear in journals of international law and crime, not in journals of international security or international politics. In other words, to political scientists, this is not a political science problem. For them, it is an organized crime problem related to narcotics or corruption. The literature has not linked the small arms issue with terrorism, for example, in a theoretically or empirically robust way.

Since there is no political science literature on weapons trafficking for me to lean on, the best I can offer is to speculate about how my colleagues would write about this issue if they did take it on. The answer in brief is they would assume a rationalist and a materialist stance. My functionalist colleagues would focus on strategic military threats and ask how weapons trafficking addresses those challenges. My factionalist colleagues would focus on procurement policy and shift the lens away from overarching military needs and onto domestic political conflicts. Geostrategists would emphasize global conflicts and shifts in world order as an external driving force pushing actors to acquire arms. If you think about the case of Israel, for example, and if you use a functionalist lens, you will see the young state of Israel seeking from its allies the weapons that it needs to defend itself in 1948. The suppliers are Czech, with the Soviet Union’s blessing. France, later on, becomes a primary source of munitions. And then very late in the process, after Israel has survived most of its existential conflicts, the United States steps in. But now that the United States has stepped out, who would Israel turn to given that the United States and Israel are cooperating on weapons manufacturing and that the other competitors in the Middle East, and in Russia and China, have little to offer on that front?

The functionalist approach would also emphasize how the United States is tying Israel to the U.S. economy by offering a very substantial amount of foreign aid. Israel is sometimes the number one or number two recipient of foreign military aid from the United States, which it uses to buy American weapons in the United States. Israel cannot use that aid for any other purpose.

The factionalists look at the domestic drivers of munition purchases. They would be interested in seeing how leaders in Israel–or in any other country–decide between foreign purchase, which creates dependency, and domestic production, which encourages development and local investment. For Israel, this was an investment in Elbit, in Rafael, and in the Israeli military industry that rose and fell depending on the extent to which France, the United States, and Britain were willing to help or not. When you get help from your allies, it suppresses your domestic production. When your allies fall by the wayside, like the French did in 1967 by abandoning the Israeli alliance, you become more independent.

The geostrategic lens would focus on armament levels in the Middle East by looking at Cold War effects. The Arab-Israeli conflict would not have lasted as long as it did and would not have led to such a high number of fatalities had it not been a game played by the United States and the Soviet Union to sell weapons, to use weapons, and to try out tactics and strategies that were attached to those weapons.

There are two modest exceptions to this relative disinterest among my international relations colleagues: one, scholarly progress on the institutional front and, two, some exciting work on norms in arms trafficking. In the first group are scholars who study the growing efforts to prevent and combat illicit trafficking. They note that regional organizations like the European Union, the Organization of American States, Mercosur, and the Organization of African Unity, among others, have stepped up their efforts. These scholars place particular hope in the United Nations to organize conferences and develop protocols against arms manufacturing and trafficking. Several of those exist and they work to some extent. States are increasingly coordinating on regulating legal arms transfer, coordinating arms brokering, marking and tracing firearms, managing weapon stockpiles and destruction of those stockpiles, and collecting arms from civilians.

An even smaller group of scholars is interested in how these regional and international agreements are fostering shared global norms around the excessive and destabilizing accumulation and transfer of small arms and light weapons, in particular, as they cause and exacerbate conflict. These norms include passing more stringent national legislation, implementing better arms transfer licensing systems, enhancing border controls and customs authorities, and improving international information exchange. In my mind, the most fascinating literature on this topic, which I note is very small, is less interested in international norms against trafficking and more concerned with the normative foundation of the trafficked weapons themselves.

Most scholars study trafficking from a rationalist perspective. These scholars, on the other hand, are interested in weapons as symbols of modernization and sovereignty. They view their production and purchase as signals that states send one another to demonstrate their reputations. Let me conclude with a quote from Mark Suchman and Dana Eyre: “It is all too easy to fall into the trap of assuming that the reason human beings arm is to fight and the reason they fight is to win. If instead we take weapons seriously, not only as tools of destruction but also as sacred symbols, we may gain a better understanding of the role of war in our world view and of the role of the warrior in our cultural ethos. Ultimately, we may find that to prevent the irrationality of armed conflicts we must first understand the nonrational meanings that we have constructed for our acts of arming and for our armaments themselves.”2

Daniel J. Sargent is Associate Professor of History at the University of California, Berkeley. His publications include A Superpower Transformed: The Remaking of American Foreign Relations in the 1970s.

I would like to focus on the relationship between arms – that is, arms as a constituent element of what we might call the American world order or Pax Americana – and American hegemony. And I want to start from the presumption that the intimate place of arms in the making of an American centered world order, a Pax Americana, is profoundly ironic. After all, President Woodrow Wilson, whom diplomatic historians commonly identify as the founding father of American internationalism, issued fourteen famous points. His fourth point was: “Adequate guarantees given and taken that national armaments will be reduced to the lowest point consistent with domestic safety.” At the time, American conceptions of international order were profoundly antagonistic to this phenomenon of the international arms trade, which would become over the long arc of the twentieth century an important component of a U.S.-centered hierarchical international order.

The interesting question for me as a historian is how did this happen? In the 1920s, after the Senate’s rejection of Woodrow Wilson’s League of Nations treaty, the United States participates in a series of international efforts to control and corral the international arms trade. In the early 1920s, the United States hosts a set of naval conferences intended to reduce naval armaments. The United States also participates in a series of ill-fated disarmament conferences in Geneva that ultimately culminate in an unsuccessful Geneva disarmament conference in 1933. Throughout this phase, a movement of historical revisionism concerned with the nefarious relationship between arms and finance in the genesis and waging of World War I animates public intellectuals, policy-makers, and ordinary citizens to take a strong and robust stand against the arms trade. Bestselling books are published, with titles like Merchants of Death and War Is a Racket. They give a sense of the animus with which Americans in the 1920s and 1930s viewed the international trade in weapons of war.

In 1935, the Nye Committee in Congress convened a series of hearings to examine the relationship between the arms trade, international finance, and U.S. participation in World War I. The committee’s conclusion was that there was a nefarious linkage and that the arms industry was squarely responsible for dragging the United States into war. The outrage that the committee’s hearings fueled propelled a turn away from the international arms trade in U.S. domestic politics in the 1930s. This mood was manifested perhaps most consequentially in the series of neutrality laws that the Congress passes beginning in 1935 that seek to circumscribe future U.S. participation in the international trade in weapons. Now, we should acknowledge that the prohibitive turn in U.S. attitudes toward the arms trade is not always beneficial. When a civil war breaks out in Spain in August 1936, the U.S. Congress quickly places an embargo on U.S. arms exports to the Spanish republic. This embargo has the direct consequence of facilitating the Franco nationalist insurgency’s overthrow of the Spanish republic. Denied the weapons of war with which it might have defended itself more adeptly against Franco’s armies, armies that were supported with weapons from Germany and Italy, both fascist powers, the Spanish republic falls to defeat. And the United States, in a sense by imposing an arms embargo, becomes complicit in the overthrow of a liberal democratic republic at the hands of a fascist insurgency.

In the late 1930s, the Nazi consolidation of power in Europe pushed the United States to reexamine and reconsider its relationship to the international arms trade. Beginning in 1939, Franklin Roosevelt started to prepare the United States for possible embroilment in World War II and to provide whatever assistance possible to Great Britain. Yet domestic isolationism, a potent political force, thwarts Roosevelt’s efforts to ready the United States for war and to aid Great Britain. Running for reelection in 1940, FDR feels called to promise an audience in Boston, Massachusetts, “Your boys will not be sent into any foreign wars.” The mood of political isolationism in the United States is so strong that Roosevelt has to abandon the very possibility that the United States might directly involve itself in Europe’s wars. Instead FDR devises an alternative strategy for aiding Great Britain and countering the Axis powers: he sets the United States up as an arms dealer to the democratic world. This strategy is encapsulated famously in the arsenal of democracy speech that Roosevelt delivers at the end of 1940. Cognizant that the American people are not going to tolerate direct U.S. involvement in World War II, Roosevelt instead proposes to make the United States the arsenal of democracy, to furnish the fruits of American industry to benefit the British and, after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, the USSR too, and to support these powers in their war against Nazi Germany.

Of course, Pearl Harbor in December 1941 transforms the strategic landscape and makes it possible for the United States to involve itself directly in World War II to counter the military and geopolitical threat of Nazi Germany. And after the war, arms become an integral modality of American Cold War hegemony. The United States quickly established itself as a guarantor of security to subordinate allies, and these security guarantees are encapsulated most famously in Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty of 1949, a clause that commits the United States to the security of its West European allies. Yet the United States also strives to uphold the security of its allies through the direct provision of weapons of war, through the military assistance program that Congress enacts in the 1950s. The United States throws open the doors of the armory and invites Europeans to take what they need. The only prohibition is on American transfers of nuclear arms to Western Europe, but even here the United States shows some flexibility. The United States will not sell nuclear weapons to its West European allies, but it does create in the 1950s a variety of schemes for giving West Europeans de facto control over U.S. nuclear weapons.

Arms in the context of an escalating Cold War become an essential part of the international order. As the Cold War intensifies, the United States assumes on behalf of its allies responsibility for security. This is a point worth pondering. Security historically in the Westphalian era has been a defining attribute of sovereignty. What makes a state a state is its capacity to protect its citizens against untimely violent death. In the context of an escalating Cold War, the United States will come to exercise this determinative attribute of sovereignty on behalf of its subordinate Cold War allies. The model that is deployed in Europe will be deployed elsewhere in the world. The United States forms relationships and military cooperation in Latin America and establishes a raft of bilateral security agreements in East Asia. It builds regional security frameworks in Southeast Asia and elsewhere, including in the Middle East.

As the Cold War progresses, the retreat of European imperialism from the decolonizing and increasingly postcolonial world pushes the United States to expand its role as a provider of arms. Arms become increasingly a vital guarantee of regional security and of U.S. hegemonic power. An illustrative case in point will follow the British retreat from military positions east of Suez in 1967. After the British decide that they can no longer take responsibility for providing military security in the Persian Gulf, American officials ponder the question of how regional military security in the Persian Gulf region will be assured. The Nixon administration formulates an ad hoc solution whereby the United States will provide weapons of war to Iran and Saudi Arabia, which become the twin pillars of American regional security strategy in the Persian Gulf. To this end the United States once again throws open the doors of the armory. In a remarkable 1972 meeting between the Shah of Iran and the President of the United States, Iran tells the United States that it is willing to purchase any weapons that the United States has to sell. Even more striking, President Nixon tells the Shah of Iran that it is okay for Iran to increase oil prices in order to be able to pay for the weapons that it’s going to be importing from the United States.

In the 1970s, Iran becomes the world’s single largest importer of weapons. It builds a remarkable arsenal that includes the world’s largest fleet of military hovercraft, a quite remarkable sort of expression of Iran’s military capability. Of course, we know how this story ends. Iran in the 1970s is a parable cautioning against the pernicious and destabilizing effects of the international trade in arms. Indeed, there is a powerful case to be made that the Shah’s preoccupation with building up Iran’s military power contributed to the country’s destabilization and in 1979 to the overthrow of the regime. However, I am not certain that we would rush to that cautionary conclusion. Let me make three points by way of conclusion.

First, we should always be mindful that the decision for a superpower like the United States to withhold participation in the international arms trade is an ethical choice, just as providing arms to weaker powers in the international system is an ethical choice. Think of Bosnia in the 1990s, for example. The arms embargo that the international community slapped on Bosnia in the context of the Bosnian civil war made it very difficult for the Bosnian government to protect itself and its civilians from vicious and violent attacks staged by internal insurgents with weapons of war provided by rogue powers, the Republic of Serbia most consequentially. We could also think of Syria since 2011.

Second, states that lack arms industries depend upon the international arms trade in the twenty-first century in order to be able to exercise what Max Weber defined as a defining attribute of sovereignty, namely, the capacity to exercise legitimate violence. Brian showed in his talk what happens in places like Mexico today, where states lack effective monopolies over the exercise of violence. Chaos and mayhem can easily ensue. As the world’s largest exporter of armaments, the United States is perhaps singularly capable of providing other states in the international system with the means of destruction necessary to exercise legitimate monopolies over the use of violent force. This is a remarkable power and the United States should be very wary of using this power frivolously without due care and consideration. It is also important to remember that the arms trade constitutes a lever of power that can enable the United States to influence in more positive ways the internal conditions of countries that receive arms from the United States.

The tethering, for example, of specific human rights conditions to arms deliveries can function as a means to ameliorate human rights depredations in countries that receive weapons of war from the United States. In Latin America, for example, during the 1970s the tethering of human rights conditions to military assistance may have served to nudge the trajectory for human rights in Argentina in the right direction, just to describe one case. We should also consider on this point a scenario in which the United States unilaterally restrains its role as a deliverer of weapons to developing societies. Would the world be safer, would developing states be more secure, if the United States ceded this vital lever of power and influence to Russia or China? It is something to think about.

Finally, the alternative to U.S. arms trading may be worse. Here the Iranian case is instructive. Let us think briefly about what happens in Iran subsequent to the revolution of 1979. In the aftermath of the Iranian revolution, the Carter administration contemplates how regional military security in the Persian Gulf region will be provided. Bereft of alternatives, the Iranians can no longer be relied upon to police the gulf, and so the Carter administration decides that the United States should adopt and exercise direct responsibility for assuring military security in the Persian Gulf region. The United States creates a regional military-security architecture that evolves in 1983 into U.S. central command, the first of the unified combatant command architectures that today envelop the planet. In the absence of relationships whereby the United States equips allies with responsibility for exercising regional military security, the United States may feel called upon to exercise such military functions on its own. I think we should be aware of the escalating and cascading responsibilities that can ensue from this alternative scenario for security provision.

Let me add that we should always be aware of the costs that arms control can embroil us in. The United States over the long arc of the twentieth century created a hierarchical international order in which arms became a defining modality of international power. Today such relationships may have metastasized into a political and constitutional crisis that threatens the very fate of the republic itself. After all, the U.S. Congress in 2014 began to appropriate funds to support Ukraine in its struggle against Russia. Since then, Russia has invaded Crimea and supported insurgents in Eastern Ukraine in the Donbass region. The United States has strived to support the government of Ukraine in its efforts to maintain regional security within its sovereign borders. Yet the relationships of dependency that the arms trade has helped to build between the United States and Ukraine tempted the incumbent president, Donald Trump, to use arms trading as a lever from which to extract specific political favors from the Ukrainian government, and the consequences have today propelled the United States to the cusp of the severest constitutional crisis since Watergate.

In conclusion, the levels of inequality that the international arms trade creates and that have been integral to the American world order since 1945 embroil states, including the United States, in relationships of hierarchy as well as of mutual vulnerability that can redound to the detriment not only of the powerless but also, as we see today in Washington, of the most powerful.

© 2020 by Brian DeLay, Priya Satia, Ron Hassner, and Daniel J. Sargent, respectively

To view or listen to the presentations, visit www.amacad.org/events/arms-trafficking-past-present-future.