April showers may bring May flowers, but May flowers among archival materials can bring a host of problems.

Most of the materials in the Academy’s Archives are paper-based documents and bound volumes, dating from the twentieth century. Some materials are in other formats, such as photographs and negatives, magnetic audio and video tape, and three-dimensional artifacts. Many of these materials are in stable condition and are easily preserved with the proper combination of stable environmental controls and archival preservation methods.

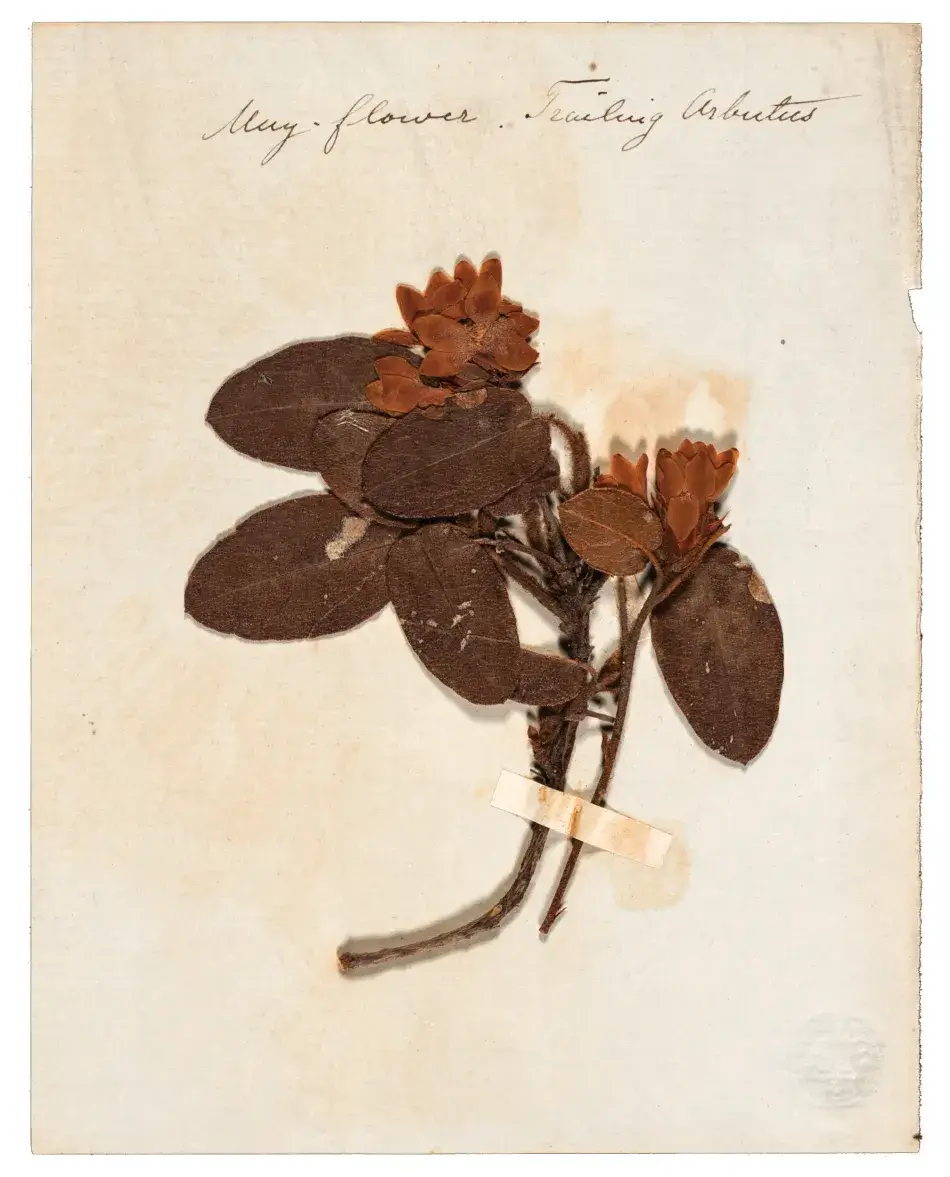

Some objects, however, pose particular challenges for long-term preservation. For example, the document shown here–sent to the Academy by chemist J. Davenport Fisher sometime in the latter half of the nineteenth century–features dried, pressed trailing arbutus (also known as mayflowers) adhered to a brief note. Though the flowers are pressed, they are not perfectly flat, affecting the way the document is housed in a folder. The naturally occurring pigmentation of the plant, particularly of the flower petals, has begun to break down and stain the underlying paper. The organic matter itself is a lure for insects or other pests.

To protect this item and other materials like it, several procedures have been implemented to mitigate the preservation challenges as much as possible. The letter, with the flowers still intact, has been removed from the box where it was originally housed and placed in a separate archival document case. The letter has also been placed in an enclosure of acid-free paper that is positioned inside an inert polypropylene sleeve. In addition, the environmental controls within the Archives facility keep the object at a stable temperature and relative humidity to slow the desiccation of the flowers.

The donor of this object is identified as J. Davenport Fisher, but the date of transfer is unknown. Born in March 1832 in Boston, he earned his Ph.D. in chemistry from Heidelberg University (Ohio) in 1855. In 1860, he donated five volumes on chemistry to the American Academy. During the Civil War, Fisher served for two years as a lieutenant in the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry. After the war, he taught chemistry at the Naval Academy in Annapolis and maintained ties with scientists back in Massachusetts, including Academy President Asa Gray. Settling in Milwaukee, Fisher continued to practice as a consulting chemist. Tragically he was killed by an electric streetcar in October 1911 at the age of seventy-nine.