When it is recollected that Agriculture is the most beneficial of all human employments, and that it is the support and the source of riches and grandeur to most nations and kingdoms in the civilized world, and particularly when we are are [sic] convinced that it is essential to the prosperity and perhaps the very being of this Commonwealth, I presume that any suggestions concerning it or any efforts to promote it will at least be pardoned if not applauded.

Benjamin Guild to James Bowdoin, [1785 August 24]1

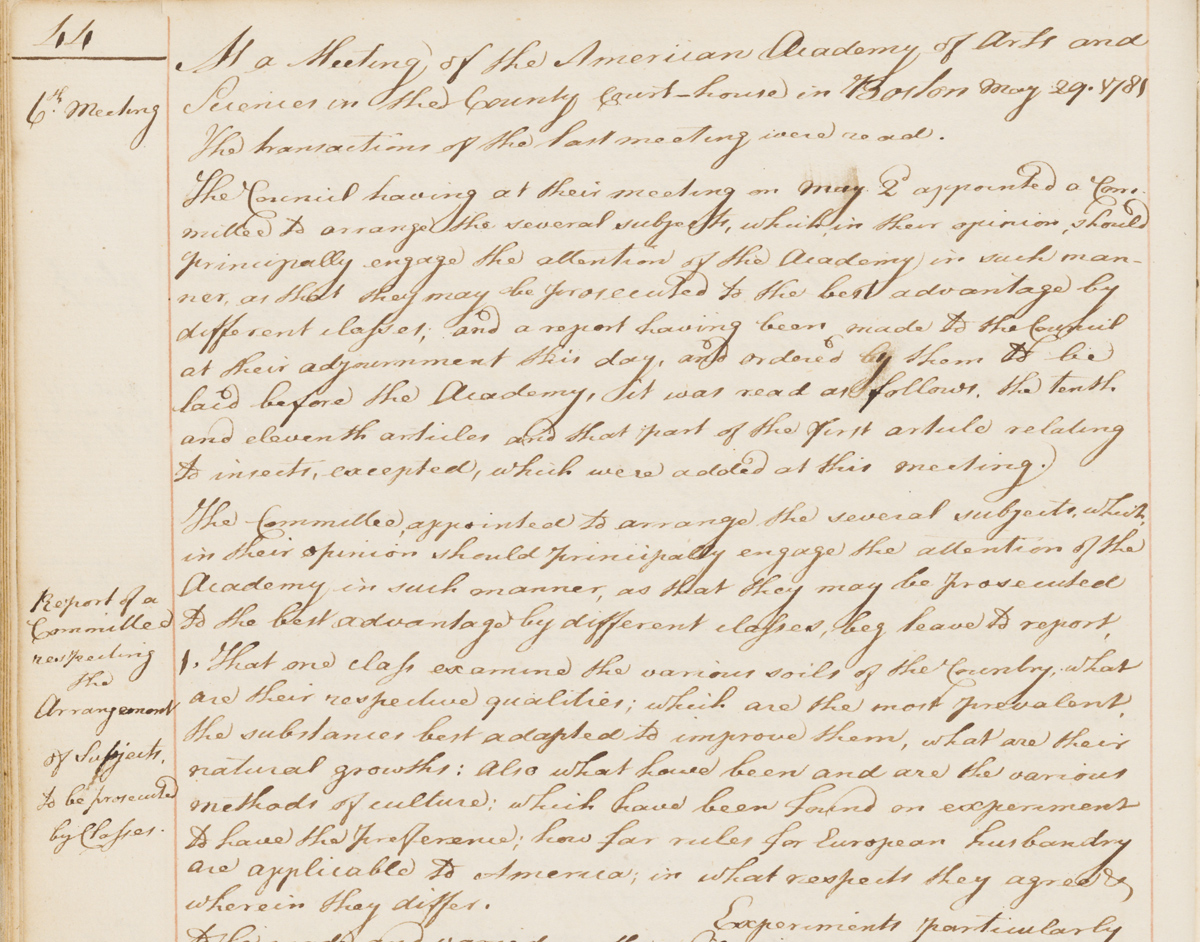

Shortly after its founding, the Academy sought to establish more firmly the intellectual pursuits in which it would engage. To this end, a committee appointed “to arrange the several subjects which… should principally engage the attention of the Academy” reported in May 1781 on eleven proposed subject areas that the members felt would best benefit their new country and its citizens. Of those eleven, the first four pertained to agriculture and natural resources:

- that one class examine the various soils of the Country, what are their respective qualities; which are the most prevalent, the substances best adapted to improve them, what are their natural growths : also what have been and are the various methods of culture : which have been found on experiment to have the preference : how far rules for European husbandry are applicable to America; in what respects they agree & wherein they differ. Experiments particularly to be made and varied on the Siberian wheat. Also that this class endeavour to ascertain the origin, progress and periods of the various insects, which infest fruit and other trees and vegetables and the best methods of guarding against the evils hitherto consequent upon their appearance.

- That a second class examine the growth of vegetables and remark the various phenomena observable in them through the Seasons; that they collect and preserve the seed, leaf and flower of the various vegetables in the country, determine their proper names and give a particular description of them, especially of those peculiar to America.

- That a third class collect samples of the various minerals and fossils in the country and describe their situations and the quality of their respective soils.

- That a fourth class make a chemical analysis of vegetables, minerals and fossils and ascertain their medicinal and other properties.2

Once these areas of study were approved by the membership, the Academy advertised in New England newspapers, asking for submissions from the general public on agricultural methodology and practices. Of the essays and treatises received in the first few years, many are still available in the Academy Archives.

At least ten such communications were published as “Physical Papers” in the first two volumes of Memoirs, including:

“Observations on the Culture of Smyrna Wheat” by Benjamin Gale (Volume 1, 1785: pp. 381-382)

“On the Theory of Vegetation” by Noah Webster (Volume 2, 1793: pp. 178-185)

The Academy reiterated the importance of this area of “practical knowledge” in the Preface to the first volume of Memoirs: “To some readers, the subject of many papers, which have a place in the physical part, may seem unimportant ; but it ought to be remembered, that one interesting pursuit of the Academy is the natural history of their own country ;— a country, where the arts of defence and the means of subsistence have, hitherto, almost engrossed the industry of its inhabitants ; where the fossil and vegetable kingdoms are yet unexplored, and perhaps, their most valuable productions still undiscovered…”3

Even the seal of the Academy includes a testament to the importance of agricultural knowledge to the prosperity of the nation and its people. “The principal figure in it is Minerva. At her right-hand is a field of Indian Corn, the native grain of America. The prospect on that side is bounded by an hill, crowned with Oaks... About the feet of Minerva are scattered several instruments of husbandry.”4