2128th Stated Meeting | September 22, 2024

The closing program of the Academy’s 2024 Induction weekend featured a presentation by new member André Fenton about the science and stimuli of memory, followed by a conversation with incoming Academy President Laurie L. Patton. An edited transcript of the presentation and conversation follows.

Laurie L. Patton

Laurie L. Patton began her term as President of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in January 2025. She previously served as the 17th President of Middlebury—the first woman to lead the institution in its 224-year history. She was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2018.

It’s wonderful to see everyone this morning. I hope you’re rested and refreshed. Our program today is not the Induction Ceremony all over again, but something else entirely. We hope the program is fun and an informal conversation between friends. By now, at this moment in the weekend, I’m hoping you are over your imposter syndrome and just happy to be in the company of people who like to talk about ideas.

It’s my pleasure to introduce our speaker. I think André Fenton was chosen because of the almost universal fascination with the question of mind and memory. Let me share a little bit about his background. He knows how to work with humanists, scientists, social scientists, and artists because he’s a deeply interdisciplinary person.

André Fenton grew up in Guyana and Toronto and was educated at McGill University. His undergrad thesis was on the neurobiology of crickets. And his first job after college was at the Czech Academy of Sciences in the research group of Jan Bureš, studying the hippocampus. He earned his doctorate from the State University of New York, where he looked at how cues affect the hippocampus. His research broadly involves how brains create, store, and experience memories using electrophysiological experimental techniques, some of which he has pioneered himself, combined with theoretical analysis. He has also studied how the hippocampus is involved with information processing and the formation and recollection of memories across different timescales. Who isn’t interested in that? Welcome, André.

André Fenton

André Fenton is Professor of Neural Science at New York University. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2024.

Good morning. This is quite an honor, and it’s also very humbling. I could never imagine giving a talk like this to an audience like this. It’s really breathtaking that I’m here at the Academy and also a new member of the Academy. Thank you for giving me this opportunity.

We all have an intuition about what our memories are. And the ordinary intuition is that it’s something about the past. It’s how we store our past, and how we retrieve our past. For most of my career, I’ve been a memory scientist. Some might say I’m a world expert in memory, but that is a mistaken understanding. I would like to share with you my more recent understanding, which is stated in the title of my presentation: Memory Is About Your Future: What We Think We Become. Our memories are really about our futures. I’m going to make the case not just from opinion, but from the evidence that you can measure with electrodes and proteins and the anatomy of the brain. And so if that’s true, then our experiences, which are predicated in the brain, are designed in many ways by our past and inform our future and what we think we can become. So that’s the thesis of today’s argument.

Let’s start at the beginning. Slide 1 (S1) shows me when I was six years old, standing in front of my grandmother’s house in Guyana, where I was born. I used to be really embarrassed about this picture and so to get over that, I now show it everywhere! In preparing for this presentation, I wondered, what was I thinking about in this picture? And to be honest, I have no idea. And I’m a memory expert. Anything that I imagined that I was thinking is probably confabulated and made up. But what I’m really sure about is that I was not thinking about opportunity, impact, commitment, or the Academy. What I understand today is that I had an incredible opportunity because I left Guyana, went to Toronto, spent some time in the Czech Republic, and now I reside in New York. And that opportunity really came from my mother, who’s here today. I can’t figure out how to thank her for taking me out of Guyana and giving me those opportunities. And I’ve been trying to think how to give her the honor and the recognition for that. Today happens to be her 80th birthday. So, happy birthday, mom. This presentation is devoted to her!

S1

This image in slide 2 (S2) is a word cloud, which I created using a lecture that I had given that you can find on the internet. What is interesting is that the lecture is not actually about memory. But these are the concepts that occupy my mind. To give you some insight into why I use these words so often, I would like to start with my daughter Zora. In slide 3 (S3), Zora is approximately the same age as I was in the photo of me that I just showed you. Next to the photo of Zora is a painting that I would show her when she was three, four, and so on. What’s interesting about this painting is that when Zora looked at this before she was six, she would only see dolphins. Does anyone see the dolphins here? Okay, there’s an innocent there! Most people see the couple in an intimate embrace. Zora started to see the couple in an intimate embrace, which was worrisome, when she was about seven or so. But before that, she only saw the dolphins. And for those of you who are too shy to say you don’t see the dolphins, this is actually a painting of nine dolphins. We could spend most of the lecture time so that you could all see the dolphins. But trust me, there are dolphins there. What’s really important about this is that it demonstrates the thesis of what I want to show you. Zora’s experience and your experience with human intimacy change how you perceive this painting. For many of us, it’s hard to see the dolphins because from our experience we see the couple. So why is it that your experience changes your mind such that going forward you don’t see the dolphins, or it’s effortful to see the dolphins?

S2

S3

I have the good fortune to work in a laboratory that I founded: the Neurobiology of Cognition Laboratory. I’m going to talk about why we don’t see the dolphins from the point of view of the work we do in this laboratory. By the end, I hope to work through the different concepts of memory that have been traditionally used when people talk about memory, using the technology of their time. Plato imagined memory to be a wax tablet that you would inscribe (S4), and there would be a trace of experience in that tablet. Many people think of memory as being filed away in a filing cabinet or a bunch of photographs that you would put somehow in some order so you could retrieve them. And the last concept is a deep neural net, like ChatGPT.

S4

How to think about memory?

So where is memory? Is memory in the individual, in a society, in the brain, in a neural network, in a neuron, in the synapses that connect those neurons? Is it in the proteins, in the channels of those neurons, or in the DNA? The crazy thing is memory is everywhere. It is operating at all of these levels. It’s a process and not a thing. In our laboratory, we use mice because we can make manipulations at these different levels of biology. We use mathematics, machine learning tools, and some complicated things that aren’t really so complicated. I will show you some of those tools in order to make the connections across these levels.

We focus most of our studies on a part of the brain called the hippocampus. One of the things we can do is ask the mouse to learn something in a way that it can demonstrate that it learned that thing. For example, in one of our studies, we put a mouse on a rotating arena, with the computer tracking the position of the mouse. When the mouse is detected in a particular zone, the computer can electrify the floor just a little bit, so it’s unpleasant for the mouse to be in that area, and it turns off the shock when the mouse leaves. Mice don’t like to have their feet shocked, so the mouse will stay away from that area. After the mouse has learned something, we reward it by killing it humanely, slicing through its hippocampus, and then probing electrophysiologically the strength of the synaptic connections between the neurons. We can measure the synaptic response to a stimulation of neurons in the tissue.

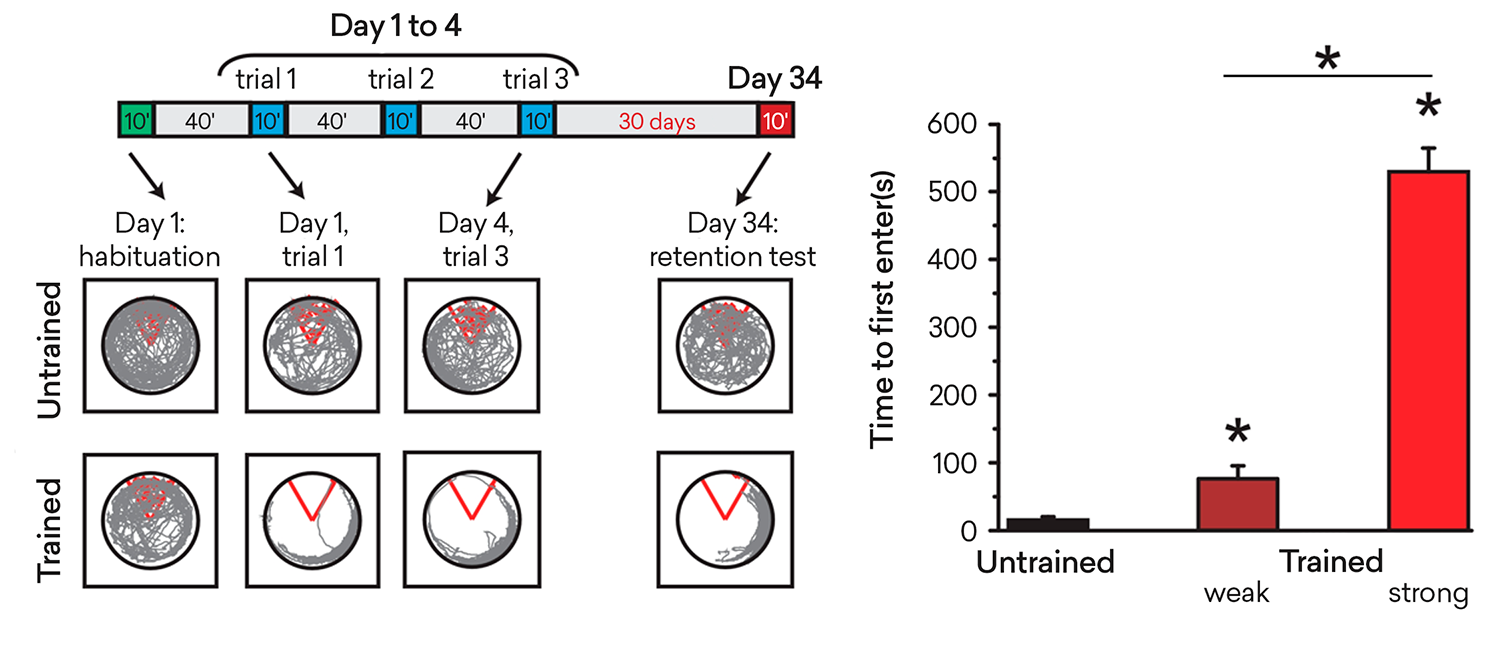

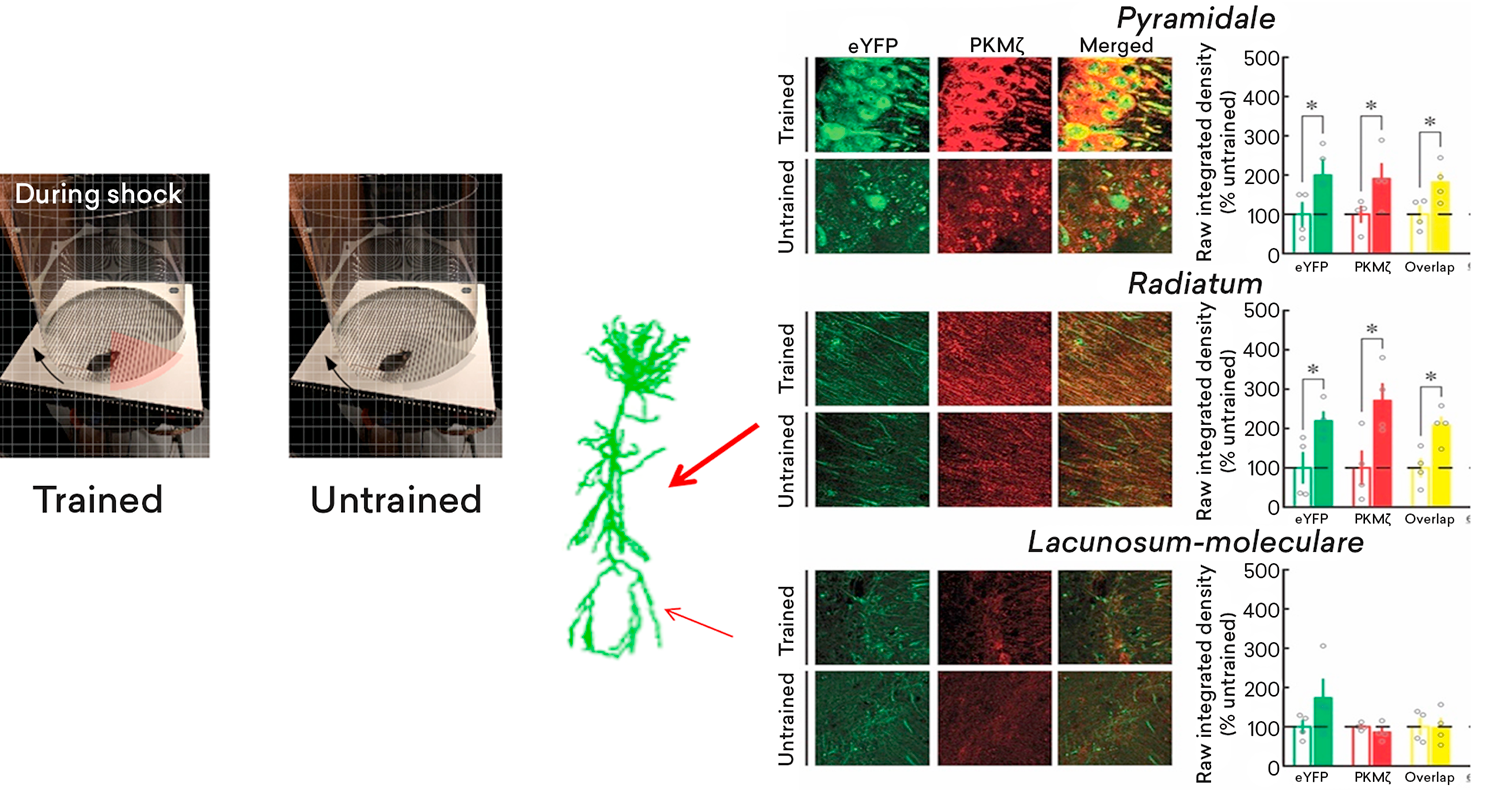

In our study, we have a control mouse that doesn’t get the training and a mouse that is trained (S5). What can we see a month after the memory has been acquired? Some mice don’t remember very well, while other mice are the good students, and they remember very well. They take ten minutes before they enter the shock zone a month later. If we look in the brains of those mice, we see a couple of things. We are measuring the strength of those synapses, that connection between one part of the hippocampus and another part. The connection is strengthened in the mice that remember, but not in the mice that don’t remember. This part of the hippocampal circuitry is changed for at least a month. Mice only live in the wild for several months. In our laboratories, they live about two years maximum. So a month for them is a very long time.

S5

Memory training causes persistent synaptic strengthening

Pavlowsky et al., 2017, Learn & Mem.Chung et al., 2021, Nature

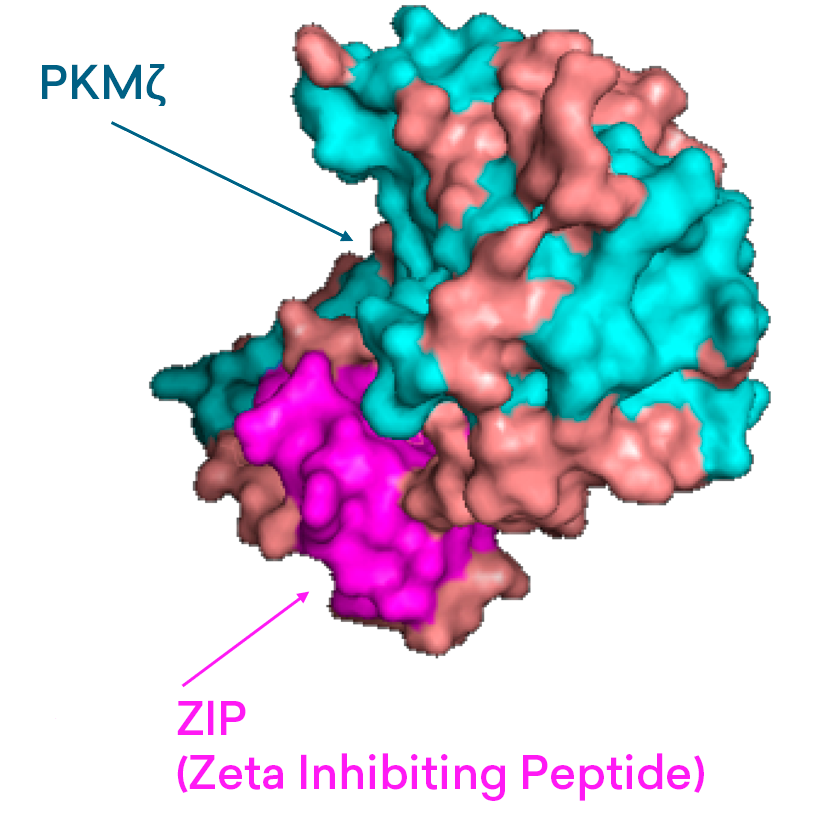

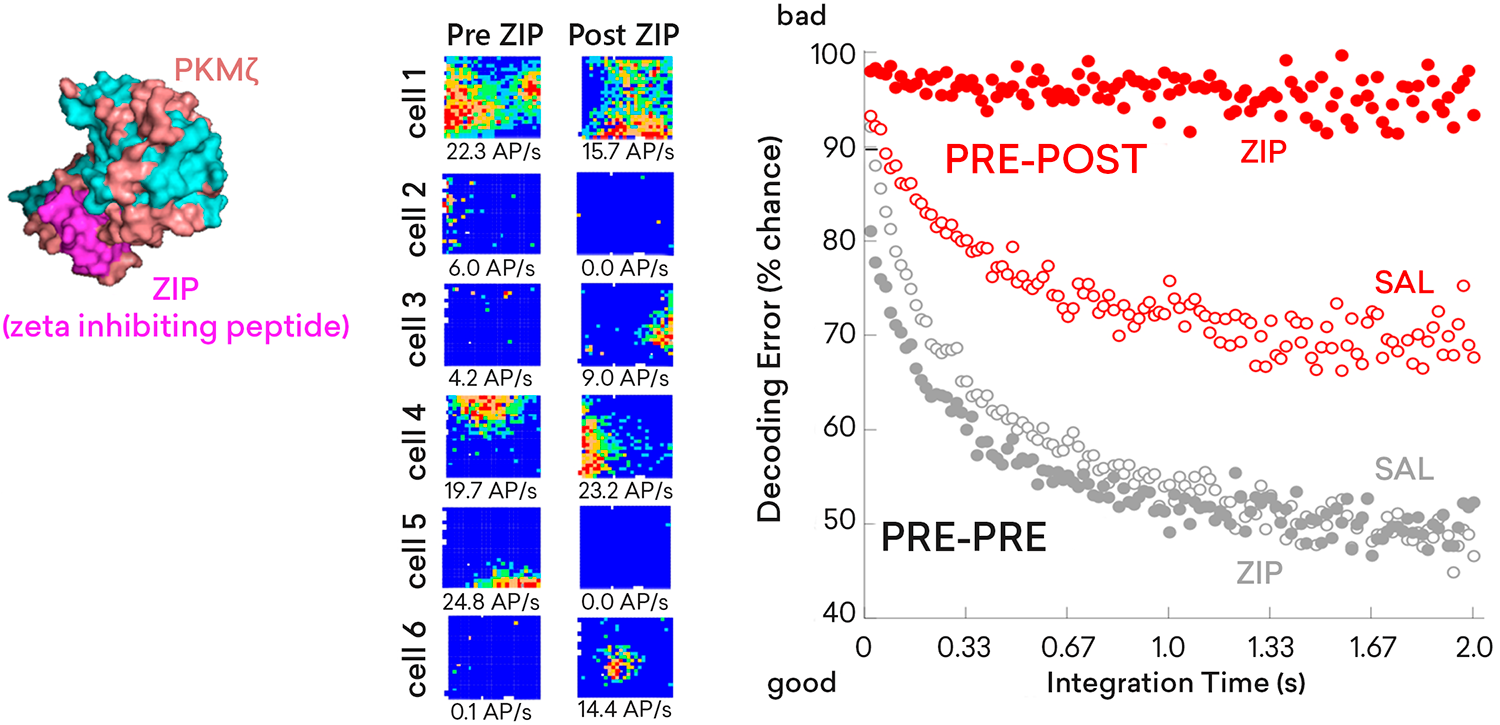

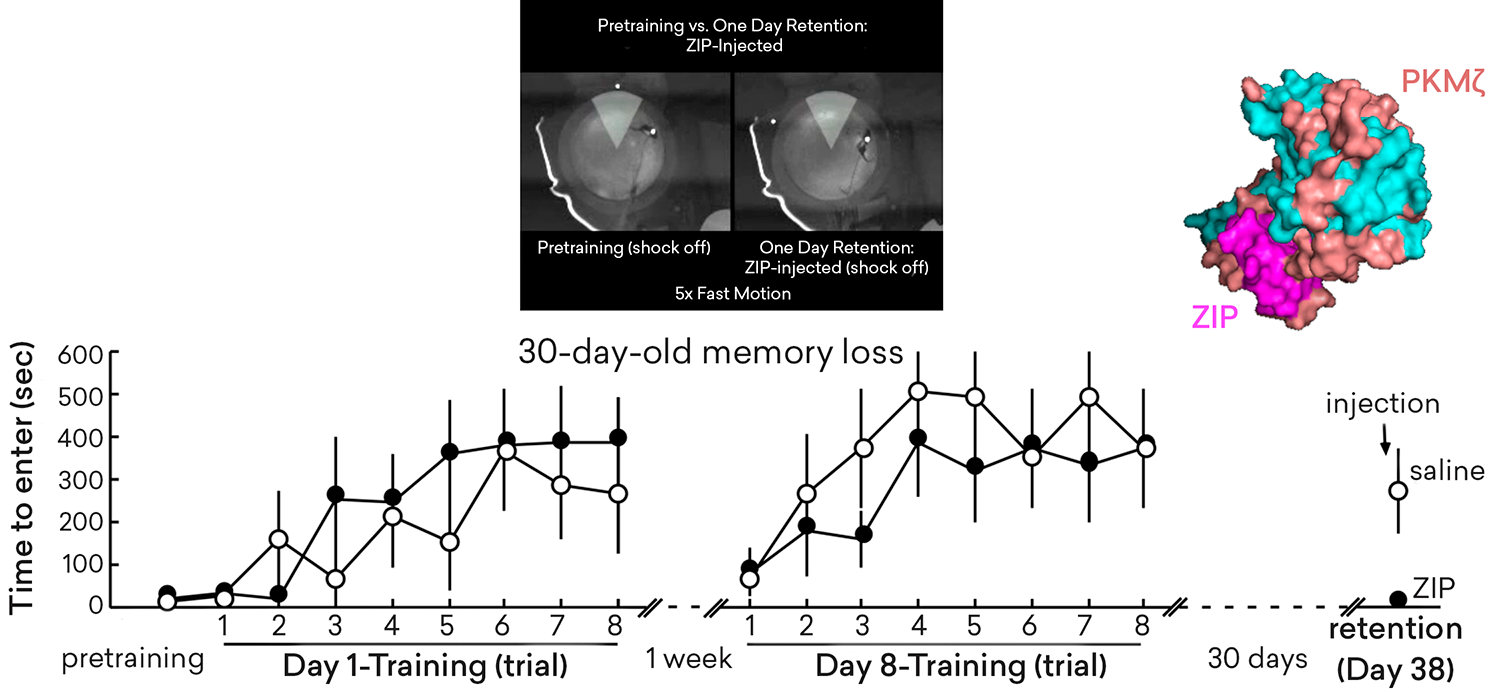

One of my favorite proteins is protein kinase Mzeta (PKMzeta) (S6). This is a model of what it looks like. The area in magenta is not part of the protein. We engineered it, and did so because it fits into that protein in a particular place to render the function of the protein inactive. It is Zeta Inhibiting Peptide. We know that PKMzeta is crucial not only for strengthening these synapses, but for the synapses persisting in their strengthened stage. We were interested in seeing where the brain makes the PKMzeta a month after acquiring the memory. But we didn’t want to look just anywhere in the brain. We wanted to look in the neurons that were crucial for memory. We can engineer a mouse so that when we remove the hippocampus, the neurons that were active when the mouse was forming the memory will be green. What we can do is mark those neurons and then wait thirty days. In our experiment, we first showed that those neurons are crucial for memory.

S6

We engineered the neurons to not just glow green, but to be responsive to light. Your brain is not ordinarily responsive to light, but these neurons are because we engineered them that way. It’s what we call optogenetics. We can tag the neurons that were active when the animal was expressing memory by avoiding a particular area, and in a control mouse we can tag neurons that were active when the mouse was exploring a neutral environment with no shock. Weeks later we can put the mice in a new lab where the mice have never been and stimulate the neurons with pulses of light. You can see that only the avoidance memory-tagged mouse has chosen a place to avoid because we are reactivating those neurons. The mouse has nothing better to do than to interpret that light stimulation as the experience of the room with shock. And so it’s avoiding a certain location that it has chosen. These stimulated neurons are essential for the expression of this avoidance memory. We can look in those neurons for the PKMzeta. And what’s crazy and cool is the PKMzeta is in particular parts but not throughout the neurons. We can measure how many neurons are green in the trained animals compared to the untrained animals. We can determine how much PKMzeta there is in those memory-trained neurons.

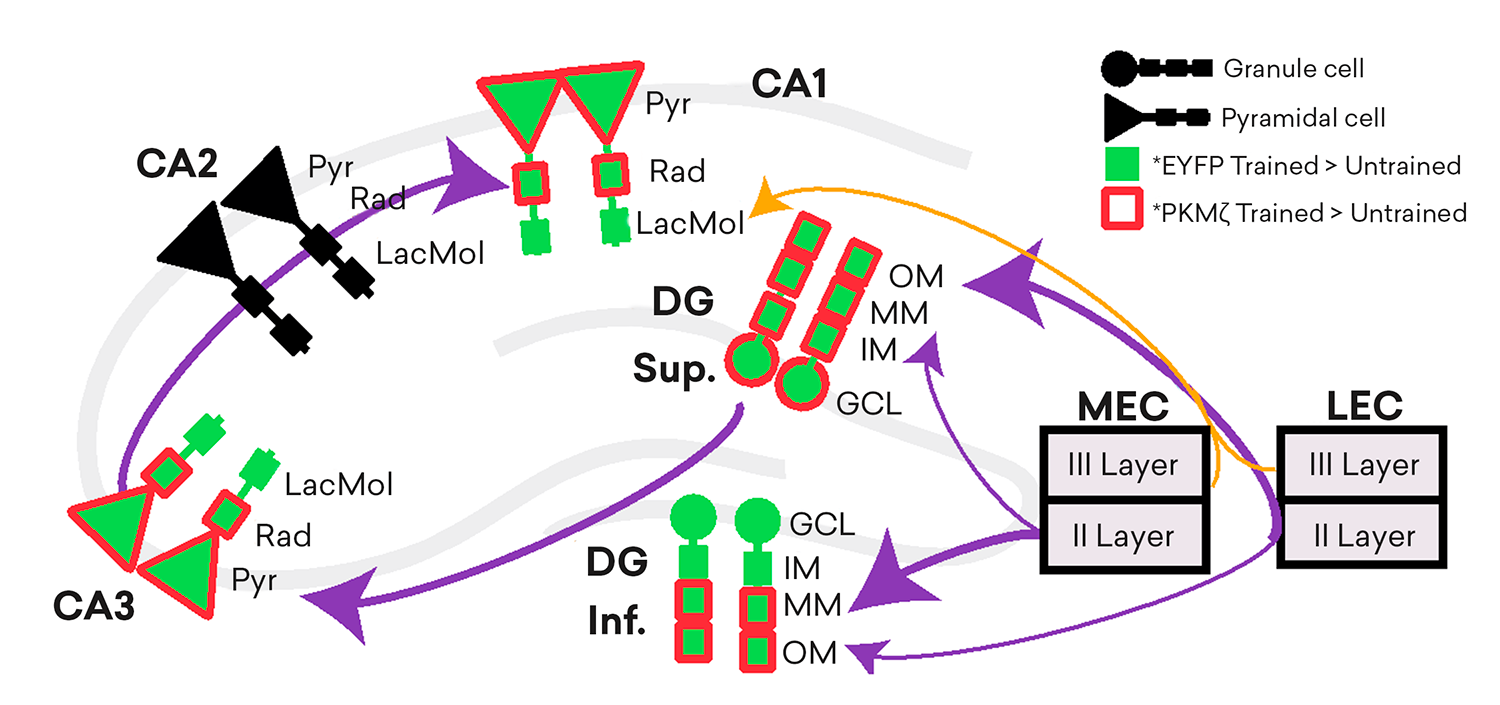

One month later, the synapse is strengthened, and there’s more PKMzeta in these neurons that are crucial for that memory (S7). There’s also a circuit change here if you look through the whole hippocampus. The green neurons are the memory-activated neurons, and the red compartments are the places the PKMzeta is elevated a month after training (S8). What this shows is that the brain as a neural circuit has been transformed. It’s persistently different. The information flow across these different parts is going to be different a month later because of an hour and a half experience that the animal had a month earlier.

S7

Memory training persistently increases input-specific PKMζ expression in memory-tagged cells

Hsieh et al., 2021, EJN

S8

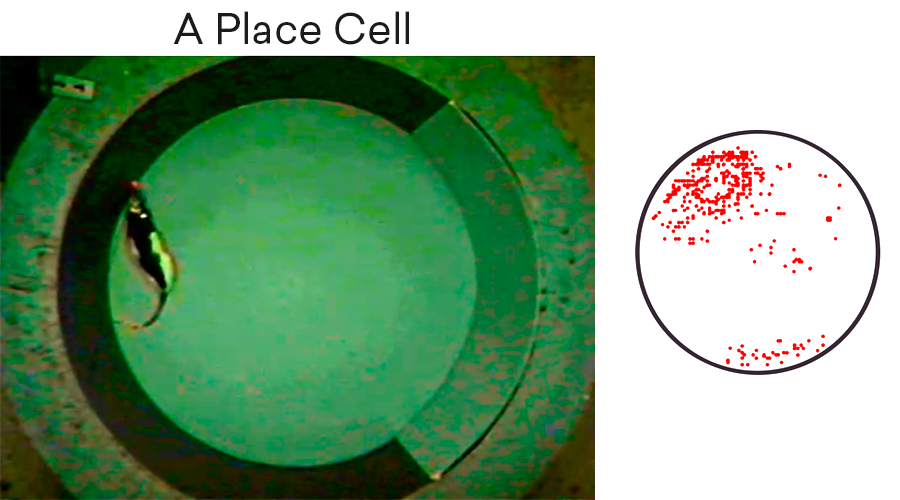

So what does that mean? A month after the learning experience PKMzeta has changed, and how much one neuron activates another is different. Well, John O’Keefe won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2014 for describing the cells that I studied as a student (S9). This neuron in the hippocampus is discharging as the animal walks around that space. We can record many of those neurons and decode where the animal is thinking it is, where it remembers it is. And this shows that we can do that decoding if we collect enough data. We use Bayesian inference in order to predict where the animal thinks it is when it is walking around that space. We can record from a few tens to a few hundreds of these cells. What’s remarkable is if we use the ZIP peptide that blocks the activity of PKMzeta, we can erase all of the information about the places from those neurons (S10). That shows that these synapses are important. PKMzeta is storing that information and we can remove that information, but not destroy the hippocampus. We can wipe the slate clean, if you will, of that particular type of information.

S9

Electrical activity in the brain

S10

Inhibiting PKMζ erases place information in hippocampal place cell firing

Barry et al., 2012, J. Nsci

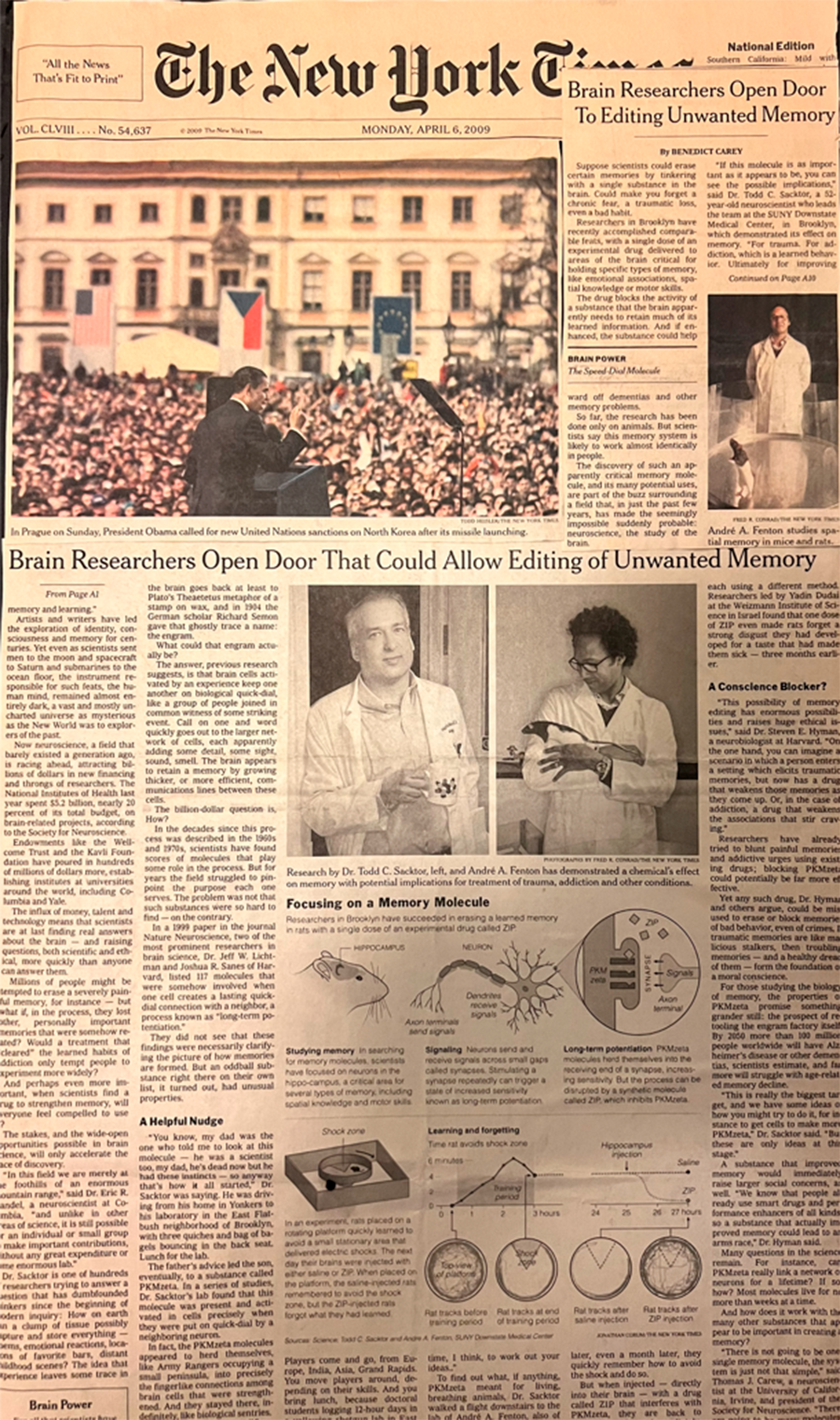

So maybe you don’t care about place cells. Not that many people do. So let’s look at memory. Eva Pastalkova did this truly heroic experiment (S11), in which we made sure the animals had this strong memory because we gave them training over two weeks, then we waited another thirty days. When we injected the PKMzeta inhibitor into their brains, they no longer remembered. We erased the memory. This discovery put me on the front page of The New York Times in 2009 (S12). That’s a pretty cool thing. And let me point out, it’s above the fold! What’s also interesting is it coincided with a photo of Barack Obama giving a speech in the Czech Republic. What a coincidence and honor to share the front page with President Obama. I was feeling pretty good. Then some papers published in Nature in 2012 claimed that everything I just said is wrong, and really wrong. Those papers reported on experiments in which they genetically deleted PKMzeta and observed that memory was fine. One of the authors is Richard Huganir, a member of the Academy, and at the time the president of the Society for Neuroscience—that itself made us nervous. But this is how science works. It turns out that we weren’t wrong, but rather something really interesting happened to create this controversy in the observations, and it took us about three years to work it out. What happened is that another protein compensated for the loss of PKMzeta; it took the place of the genetically deleted PKMzeta.

S11

ZIP erases long-term memory

Pastalkova et al., 2006, Science

S12

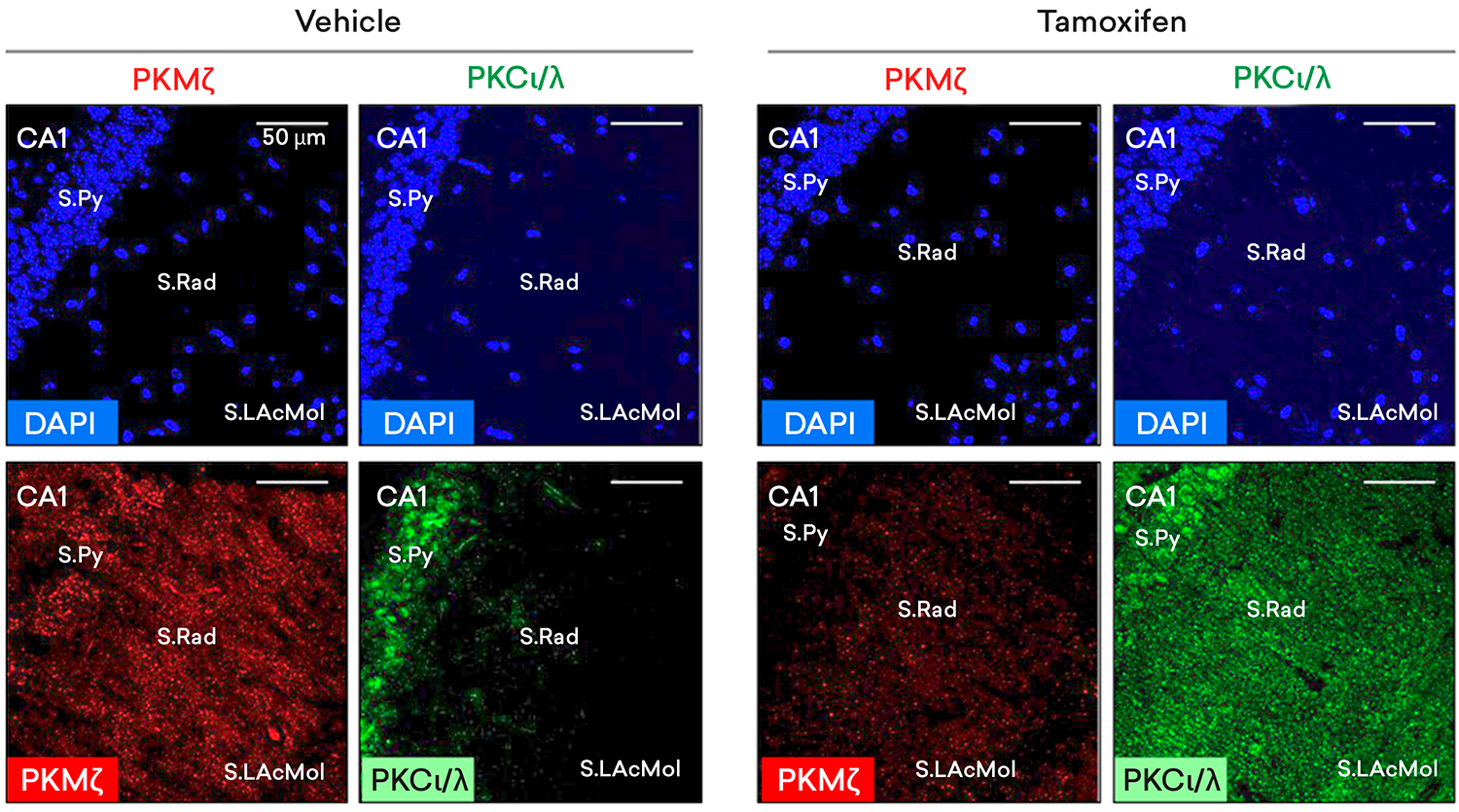

In S13, the PKMzeta is shown in red, and PKCiota/lambda, this other compensating molecule, is in green. It’s a structurally similar molecule to PKMzeta but it’s not expressed much where the memory-associated synaptic changes happened. This mouse is engineered so we can give it the drug Tamoxifen to genetically delete the PKMzeta gene. After we delete the PKMzeta protein we observe there’s suddenly a lot of this PKCiota/lambda protein where there previously wasn’t. So the PKCiota/lambda replaces, if you will, the PKMzeta. And that’s the important lesson here. There’s not one important molecule. There are interactions of molecules, and they compete for particular functions. We have to be careful about using drugs or various kinds of chemistry to manipulate these molecules in the brain because they get replaced. And there are very good biological reasons for the replacement because PKCiota/lambda is actually very similar to the PKMzeta in its structure.

S13

Prkcz deletion is compensated by Prkci

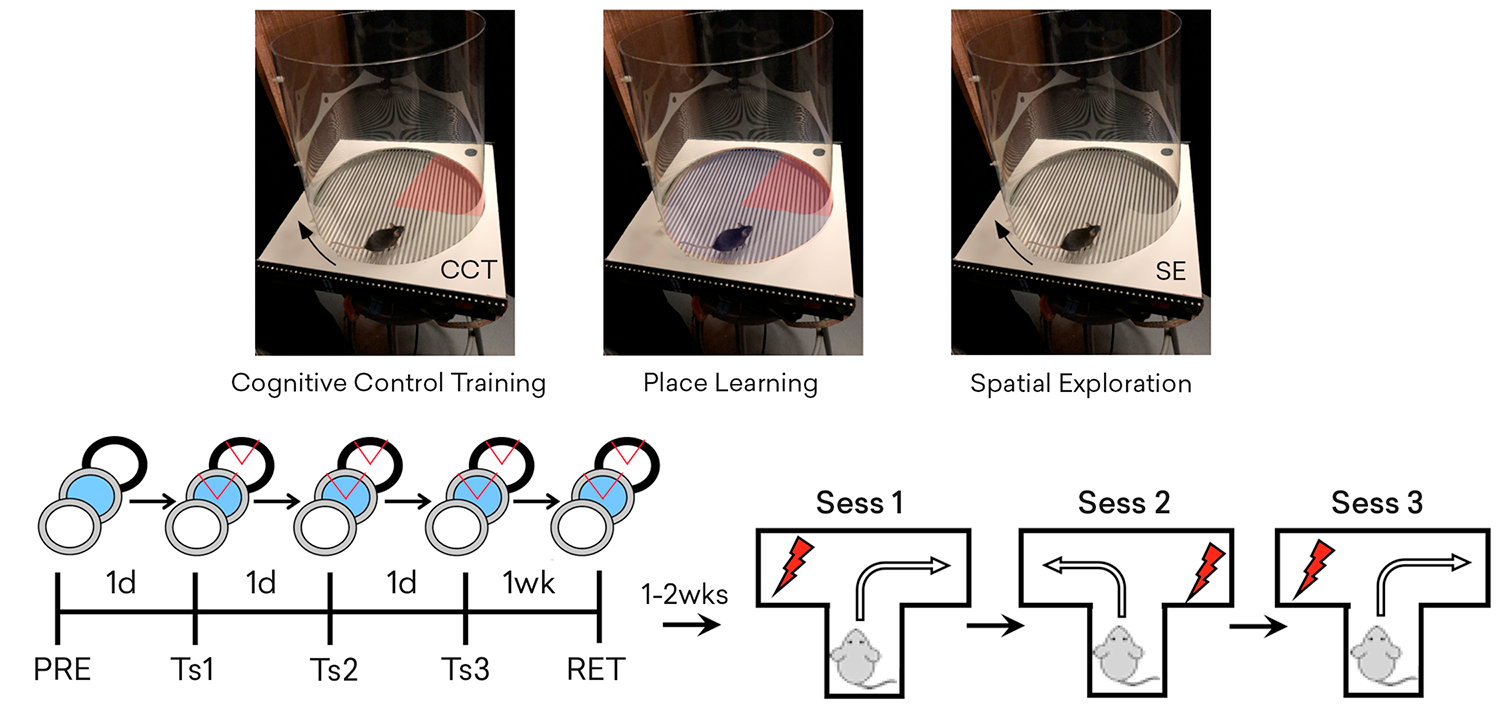

What the PKMzeta–iota/lambda labeling showed us is that they were in conflict in some way, and the conflict was resolved because there’s another molecule, KIBRA, that targets where the PKMzeta activity should be operating. When the PKMzeta is not present, then a weaker chemical interaction with PKCiota/lambda is allowed to happen. We’ve designed new kinds of drugs that interfere with these interactions without modifying the proteins themselves. So what I’ve shown you so far is that you can erase memories. But we are not simply scrambling the file cabinet or scrubbing over the wax tablet. We are affecting the function of this network. The easiest way to explain this is to describe a complicated experiment by Ain Chung (S14). She trained animals in one of three variants of a place-avoidance task using the identical rotating arena. In one variant, the cognitive control training, a mild foot shock is turned on if the mouse enters a stationary region called the shock zone. By using what they can see of the room when they are shocked, the mice quickly learn to avoid the shock zone. Note that learning to avoid the shock also requires the mouse to ignore the distracting cues like smells that rotate with the floor and define where the mouse is on the floor when there is shock. Everything is the same in the second variant, place learning, except there’s water on the arena surface. The water hides the distracting olfactory cues so the mouse has less distractions to ignore. In the third variant, spatial exploration, the arena is identical to the first variant but shock is never turned on. Because the shock duration is only half a second and the mice learn to avoid well, less than 1 percent of their experience is with the shock on and 99 percent of the time the conditions are identical between the variants. Now if you wait a couple of weeks after this training, and you put the animals in different tasks—if you put them in a maze where they have to learn to go to the right to avoid getting shocked and then switch it so they learn to go to the left to avoid getting shocked—what we observe is that there’s no difference among these three groups initially. But when you ask the animal to do something that contradicts what it had originally learned, they improve if they had this training in distraction. The training changes synaptic function and it is persistent for a month. It also changes what the animal is able to do in the future when exposed to something that has no relationship at all to what it was trained in. The circuit becomes efficient. It dampens down the small signals and boosts the strong signals. And this is one of those changes that this hour and a half of experience has permanently, or at least for a long time, maintained in the hippocampus.

S14

Place avoidance memory training causes Learning to Learn

Chung et al., 2021, Nature

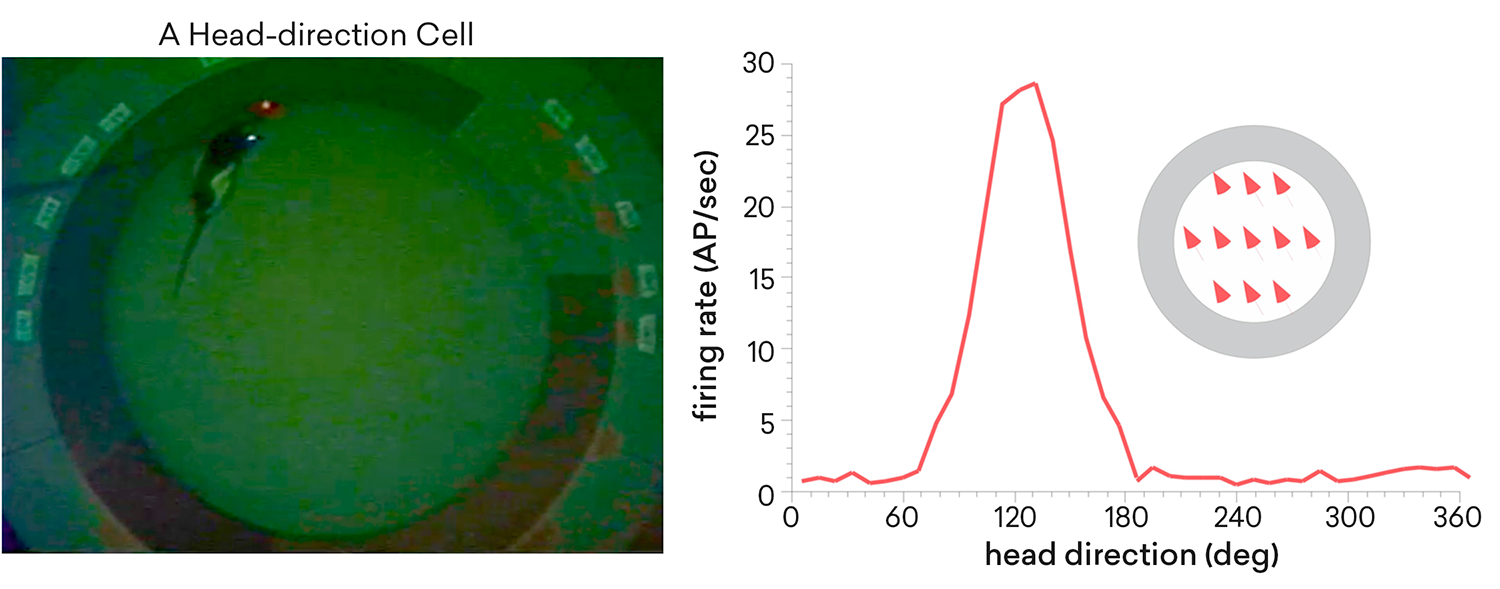

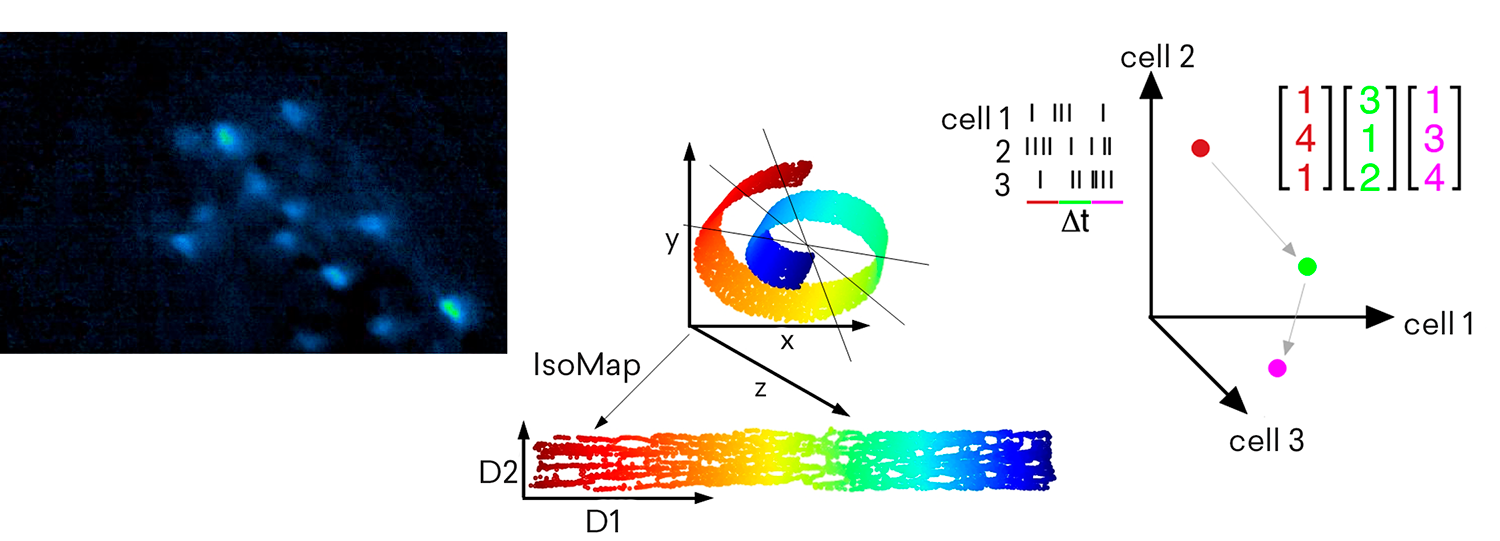

Let me give you a hint of what the activity in the brain looks like. I am going to rely on a head-direction cell because it is easier to study than a place cell. The neuron in the video fires when the animal’s head is pointing in a particular direction, let’s say about 11 o’clock or so (S15). Immensely more informative than recording one neuron, we can use novel technologies to record the activities of hundreds. The data from a population of neurons are analogous to hundreds of voices from a subset of the individuals that make up a crowd. We can describe the population activity during each short moment of time as a code by listing what each voice said in the moment. For the neurons, we call that an activity vector (S16). Each activity vector describes all the activity details of the entire population at that moment, which is a single point in the so-called state space, where the number of neurons is the number of dimensions of the space—I’ve depicted a 3-D space as an example. The population activity at any possible moment is a point in that state space and if the activity of each individual is independent of every other individual, the set of activity vectors will form an unorganized cloud of points. But like the example of the swiss roll shown here, we don’t observe an unorganized cloud when we examine the activity from a population of head-direction cells. Like people in a crowd engaged in multiple conversations, within the population, the subset of neurons that are active when the head is pointing to 11:00 tend to fire with the neurons that are active when the head points at 10:55 and 11:05, and none of them fire when the head is pointing toward 5:00. Because the population activity is not characterized by independence it can have a geometry within the state space, analogous to how points of a 3-D swiss roll organize on a lower dimensional 2-D sheet. If we use some math we can discover the topology of the neuronal population activity. If we record a population of head-direction cells, we observe that the population activity organizes as a ring (S17). The population activity of neurons recorded from other parts of the brain has a different topology like a plane or a torus, or higher-dimensional objects. With a little more math we can investigate the topological shape of the neuronal population activity to gain insight into how the organization develops, maintains, and changes in this abstract space to represent information about the real world (like direction).

S15

Electrical activity in the brain

S16

S17

We build maps, beliefs, and understandings of the world, and using head-direction cells I’ve given you an example for the direction sense. These representations are changed by our experience, and we use that to project our beliefs and our histories onto the world that we experience. That is the kind of inference you can come to from the work I’ve described. These are fundamental neurons that define the space in which you have your experience, and in my work, the space in which these mice have their experience. And if the fundamental space in which the theater for experience is subjective in this way, it’s not surprising why our perceptions of the world are also subjective. They have to be and can’t be otherwise.

What I hope you go away with from my presentation today is recognizing that we are here at the Academy because we’re interested in the life of the mind. Our minds are very powerful. They generate ideas. But those ideas are our ideas. They’re subjective. And how we manage to get people to have shared and collective ideas, so that we can work together on those ideas rather than separately, is deeply challenging. What I hope I’ve given you evidence of—biochemical, physiological, and functional evidence—is that this neuronal synaptic function, the stuff that our experience is built on, crucially determines our experience. We should be using this type of knowledge and this kind of insight to figure out how to make the world better.

CONVERSATION

LAURIE L. PATTON: That was an incredible talk. Now you realize you’re about to be interviewed by a scholar of religion and literature, right?

ANDRÉ FENTON: Yes!

PATTON: A little bit later I want to get to your personal experience in making some of the discoveries that you just shared with us. And I have a question about language, and how we might think about, talk about, and express what it is when we have a memory. But first, I want to focus on your childhood. That photo of you as a child was such a great picture. André, you had an interest in literature when you were in college and maybe even in high school. And then you took the accidental biology class that created a whole world for you. I would love to hear whether and how that interest in literature still remains for you, and whether you see any connections in the work that you do now to the idea of reading a novel. When I was at Duke, we had a faculty member who was doing a neural mapping of people reading. There’s interesting work being done there. But let’s go back even further. Do you think there’s something about your philosophical interest in the role of the imagination that got you started? And is that still there for you in some way?

FENTON: I have always been curious, at least from the time I can remember, which is when I was thirteen or so, about how I know what’s real. That has both bothered me and fascinated me. I think one of the reasons literature was attractive to me was because I could recognize that through stories, people could explore what’s real. And what was really fascinating to me is that stories are completely made up, or at least most of them are. They’re not about me, but you follow them as if they’re real. You cry, you exalt, you feel depressed, and you get invested in these things. And frankly, that seemed crazy to me. Why would that be? So, that was my initial interest. I also wanted to try to understand it through philosophy. I had English teachers who made the English classes seem like philosophy classes. And so when I went to college, I started to study philosophy, which I found, no offense to the philosophers here, very opaque. But it taught me to reason and to argue. What I’ve never forgotten is that the reason the stories are compelling is because they are stories. They have a trajectory through time. The character starts somewhere and develops. For that reason, Joyce is terrible for a casual read because you jump around too much. But for the most part, there’s a thread that tells the story. And the reason that’s appealing is because that’s how our brains work.

We work on the basis of those stories. We fill in the facts. If you want to have fun at a dinner party, say that something interesting happened to you at the Academy and let people guess what that is. And then answer them randomly. The party guests will construct a story. They will find a story in the nothingness that you offer them, because that’s what we do.

PATTON: I am going to add a little footnote about Joyce because I can’t resist. There’s a very devoted, some might even say religious, group who read Ulysses on an annual basis in celebration of Joyce. They often use it as a kind of neural map in itself. So I think there is a way in which the challenge of overcoming the basic neural construct of a story, as you were saying, could actually be in itself an activity of the brain to be studied by you.

FENTON: Absolutely. In fact, the experiment I showed you in which the control animals didn’t learn to learn, didn’t have the neural changes, is very interesting to think about. The one difference between that control and the animals that did form the changes is that the controls didn’t have to ignore the distracting cues. There’s something about having to use the effort to quell or quiet in order to focus attention. It didn’t take long but that training itself was the key to making the persistent changes that we could find. It’s not that there weren’t persistent changes; they were just much harder to find.

PATTON: Let’s stay with this for a second. If you studied the brain of someone reading Joyce and studied the brain of someone reading “Cinderella,” would you see different activities?

FENTON: I would predict you would see different activities. And in fact, Joyce is really satisfying when you learn to read Joyce.

PATTON: He’s the rotating arena.

FENTON: Yes, that’s right. He’s the rotating arena that when you learn to embrace the jumps, you recognize their connections.

PATTON: Let’s talk a little bit more about the rotating arena. I’m interested in it for a couple of reasons, especially because in higher ed administration, you sometimes feel like you’re a gerbil on a wheel. But I actually love the rotating arena much better. I’m just not sure many people will understand mice in a rotating arena without my having to explain your research. But someday it might be a universal image.

FENTON: I hope not!

PATTON: Let’s skip to something that I was planning to ask you at the end of our conversation, but you featured it in your talk so I’ll ask now. You have invented several devices, and the rotating arena is one of them. If I understand your biography correctly, the rotating arena was something you worked on right after undergrad, and then perfected it in different ways. You clearly work at the theoretical level but you also work at the pragmatic one. You’ve created a low-cost micro EEG device, which you could take to people who can’t have an EEG in a hospital. I would love to hear your stories of how you invented those things, and why it matters to you to work in that pragmatic space in addition to the theoretical space of neurobiology.

FENTON: I am interested in solving problems, and doing that gives me joy. The way it works for me is I ask myself, how would I solve this problem? What would be a really useful tool to solve the problem? And it turns out that for most problems that you want to solve that are hard, the tool doesn’t exist. So you have to step back and say, well, I wish I could have an X. And when you do that, most people who have been trained slightly differently than me say, “Well, I can’t do that because there’s no X.” My training was really fortunate. I was trained in pretty impoverished conditions. When I went to Prague, they made everything, and they knew how to make everything. They made their amplifiers, their PC cards—literally everything. And over five years or so I was taught engineering informally every evening for about an hour and a half by focusing on how to solve problems. The engineer who taught me was a Russian elderly person who didn’t speak English very well. He would say, “I’m no engineer; I’m a designer.” And so he taught me how to design things, and I’ve used that training ever since. When I look at a problem, I ask, how do I design a solution for that? Sometimes you can make a thing for that, and I enjoy making those things because I’ve been trained to find a solution by making a thing rather than buying a thing. And that’s how we proceed. So, give me a problem, and I naturally think, what are the ways to solve that? How would I design that thing? And then you do it.

PATTON: There’s a Sanskrit word for what you are saying: yukta can mean sensible, suitable, fit. It is related to the word yoga. And in contemporary India, you’ll hear people use the word jugād, “a fitting, often frugal innovation.” These are words related to the earlier Sanskrit. It literally means “making it as you go, figuring it out.” On an Indian street you will see a luxury car store next to a small bicycle stand, a rickshaw, and an oxcart that’s carrying computers. You have all of it. And it’s really important to know that that is the genius of that word jugād. For every single moment in that street scene you are making it up as you go. And in a way, you had a scientific version of that.

FENTON: Yes, I was trained to make it up as I go, but cautioned not to pretend that this is special. Make it up as you go so that other people can do it. That was the impetus. I remember very clearly being really proud as a graduate student that no one could understand my rig. It was so complicated. Wires went everywhere. And I was told, “That means you don’t understand this.” When you make it simple so that anyone can walk in and say, “Oh, wow, look at this, it makes sense,” it means you’ve thought about it, you’ve designed it properly so that it’s easy and other people can use it. My thesis mentor would impress upon me the principle of making things as simple as you can to get the job done and then be proud that it was simple so other people could use it.

PATTON: I’m impressed by the way that you’re talking about your different scientific experiences, and also describing them as social experiences. You’re from Guyana; you studied in Canada; you worked at the Czech Academy. You are currently teaching and doing research in New York City. Has the fact that you’ve had many homes affected your science or the way you think about the mind?

FENTON: Oh, absolutely. If you get on an airplane from New York and you arrive in Guyana and you get on that same airplane and leave, it’s almost like everybody literally has different beliefs. People in Guyana are interested in whether you’re Black or Indian when you’re in Guyana. And because of colonialism, it’s like they can’t get along. But if you get on the airplane to leave, then everyone’s Guyanese and united in being Guyanese to deal with the people in the country that the plane will land in. And I saw the same thing in the Czech Republic. I was one of the only Black people in town. I was both invited and rejected at the same time over the same things. That experience taught me that how I react and how other people react to me is in my mind and is in their minds. I decide how I will interpret what’s happening. And as you can see, that’s what my research demonstrates with evidence.

PATTON: In the middle of your presentation, you talked about the critique of your work and how that compelled you to think about the interaction between proteins. You realized that there was not a single answer. You actually ended up with a more complex model. Even though you’re working toward simplicity in certain ways with instruments, with ways of thinking that might be a kind of Occam’s razor in certain ways, and yet the science as you’ve developed it is actually more complex.

FENTON: Actually, I don’t think of it as more complex. We figured out the rules that make it simple. Think of a murmuration of starlings. If you want to understand those birds, you could count all the birds and track everything about each individual of the flock. But there are actually three simple rules that describe them: 1) Keep flying; whatever velocity you have, maintain it. 2) Don’t bump into anything. And 3) Do what the seven or eight nearest neighbors are doing. Those three simple rules describe what looks complex. From my point of view, we’re actually looking for something simple, something elegant, but the answer happens to be abstract.

PATTON: And it’s also a dynamic interaction.

FENTON: Yes, you have a ΔT in there.

PATTON: My last question before we turn to questions from our audience. I thought about this as I was listening to your presentation. I want to describe an experience I had with my brother. My brother and I were moving objects from my mother’s home. We just moved her into a nursing home. And it was hard. There were memories everywhere. My brain was flooded with these memories. A neighbor came by to give us tea, and when I introduced my brother to the visitor, I got his job wrong. Now I am hyper about getting everyone’s biography right, about honoring people in everyday interactions. And then I got my brother’s job wrong. But what I didn’t say at that point, partly because I had been thinking about your work, was “Oh, that was horrible and I disrespected you, and what’s going on with my brain. I must be losing it.” Instead I said, “My hippocampus is just not working today.” And I felt better because that biological fact made it okay at a certain level. But I don’t know whether it made my brother feel better. I’m thinking about our everyday use of language, and what would it look like if twenty years from now we don’t say, “I forgot that,” but instead we say, “My PKMzeta wasn’t present today.” I’m interested in that because there are other ways in which we have biologized our somatic experience because of new scientific discoveries in language.

FENTON: Absolutely.

PATTON: What do you think about that?

FENTON: In fact, I think that’s the goal. We’re interested in ourselves and how we engage with other people. And we have psychological concepts for that. Psychologists are brilliant. They can infer all of these functions without actually knowing how they were implemented. But now we don’t know if some of those concepts are actually correct. We don’t know if they’re precise. And that has caused many problems in societies and cultures. Think of something like race as an example. There is no such thing as race. It’s not in the DNA. It’s actually not a physical concept, but we’re stuck with it. It’ll take hundreds of years for us as humans to shed ourselves of those concepts. So the goal for me is to find the physical instantiations of our concepts and replace them with that kind of understanding, because our memories are often inaccurate, and we have conviction about them being correct. There’s no reason to have a war or a divorce over bad memories when it’s just in the nature of our minds. And if we all understood that I think we would be a lot more tolerant of different beliefs, ideas, and presentations. Just like you felt better, hopefully your brother would feel better if he shared the same concepts.

PATTON: That’s right. You’re sounding so Buddhist, so now we’re in the same world. Let’s turn now to a few questions from our audience.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: When I think about organisms and memory, I’m thinking about how variable natural environments are. And, of course, there’s a problem with memory, which is if the world is changing constantly, what you remember may not be of use. And so I’m curious about the adaptive value of forgetting. With your mice, is forgetting simply a random decay of memory, or is there actually an adaptive action in which at some point it is forgotten because it may no longer be useful in the world?

FENTON: I think forgetting is actually part of the process. Let’s not talk about biological memory for a moment, but instead let’s talk about those deep neural nets. Anyone trying to build one of those networks to learn something realizes that they can overlearn things. They learn all the details, and the details are not actually useful. In fact, those generative networks don’t recall anything. They’ve just learned the likelihoods of things. They’ve learned an abstraction, if you will. And so memories are mostly forgotten. Most experience is forgotten. But the statistics of those experiences remain in the network. The recollection of was there food or what type of food depends very strongly on the will, life history, and circumstances of that organism on that day. I think the insight here is not so much about the specifics unless they’re very important. We build a model of the world that’s actually adaptive and useful going forward.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: I want to ask you about learning and memory. Is the PKM family involved in learning if it’s based on a tone or a smell, and not associated with a position? And what is PKM phosphorylating?

FENTON: So, we don’t know everything about what PKMzeta phosphorylates. But there is a protein called NSF that traffics AMPA receptors into the postsynaptic density. Another is Numb, an endocytic protein that plays a role in a number of cellular processes. PKMzeta seems to operate in this biological capacity in many systems: in the spinal cord, in the various parts of the cortex, in motor learning, in tone, in fear conditioning. In one of our early papers, we cataloged a bunch of classic memories. And what was interesting is you can learn without PKMzeta. Even without the compensation, memories can form. We don’t know how they’ll form, but I’ll give you an insight into that in a moment. There are PKMzeta independent forms of memory, but those memories tend to be general. They’re like learning the context of something rather than its specifics. Driven by the KIBRA interactions there, our working hypothesis is that all memories are formed with a set of biological rules. It might be the NMDA receptor in the system; it might be the KIBRA, for example. And it’s targeting the kinase activity; you need a kinase to keep proteins activated. Consider this: Let’s say we live to one hundred years, but we know that the proteins that are essential and that maintain that only last a week. So, how do you maintain something across decades with the elements that only last a week? It’s a dynamic ongoing process, which can be solved using these manifold ideas that I’ve described without using the word manifold.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Do you choose to study shock memories because these pain memories tend to be stronger and they’re easier to study?

FENTON: So the answer is no. In fact, the shock is quite mild. And we’ve checked that the shock doesn’t make the animals any more stressed out than just walking around. And we’ve done that very deliberately, because we didn’t want to study stress and painful things. The reason we chose shock is because it’s convenient. The animals learn it very quickly. We can dissect the time course of the proteins. We can look five minutes later or a month later. I’m a pragmatist. I’m building a model of a question that I want to be able to address in a very deliberate and intentional way. It’s not meant to study something that’s global and universal. We hope that what we learn is global and universal, but we target the problem.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: For humans, what kinds of memories tend to stick the most for the strongest among us?

FENTON: For me, it’s the emotional memories. The ones that seem really important to the trajectory of my life. Those are the memories that I think I remember very clearly and very well. If you do the research, it is often the case that we incorrectly remember those memories. We remember that they happened and we remember the circumstances of them happening, but possibly because we replay them. All of this is a dynamic and subjective process. We might change the actual contents of those memories. That’s what the research suggests. The eyewitness accounts are fraught.

PATTON: From the sociology of labs to James Joyce to the neurobiology of memories, André Fenton, thank you. This was so fun and a wonderful conversation. My KIBRA activity and kinase presence about this conversation are going to last for a long time!

I hope that the topic of this morning’s conversation will be a memory for all of you, and an interpretive framework for many years to come of how you think about the world, and how you think about your own work and its relationship to the world. I hope your time here has been rejuvenating, helping you think with new energy about the work ahead, both in your own scholarship, in your own leadership, in your own business worlds. I also hope that it gives you inspiration to renew our democracy in all the ways that we know we can. Welcome again. We are so proud that you are members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

© 2025 by André Fenton and Laurie L. Patton, respectively

To view or listen to the presentation, visit the Academy’s website.