2127th Stated Meeting | September 21, 2024 | Sanders Theatre, Harvard University

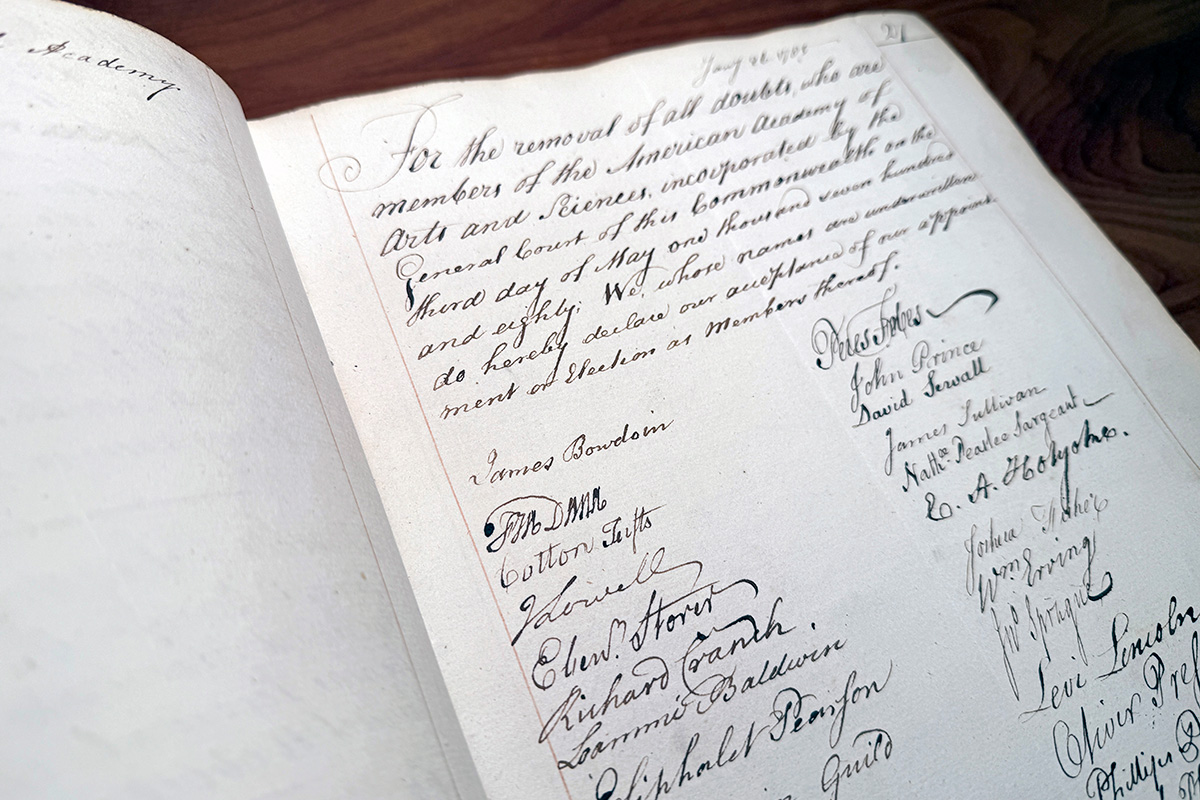

On September 21, 2024, the Academy inducted over two hundred of the new members elected in 2024. As part of the ceremony, the new members signed the Academy’s Book of Members, a tradition that dates to 1785. The signatures in the photo above are from some of the Academy’s earliest members.

The class speakers at the Induction Ceremony explored several themes, including the value of curiosity and the unexpected; strategies to prevent scientific failures with harmful consequences; the role of the social sciences in addressing the urgent challenges of today; the processes of transformation and translation; and how openness fosters innovative and sustainable problem-solving. The ceremony featured presentations from theoretical astrophysicist Charles F. Gammie, research ecologist Helene Muller-Landau, lawyer and legal scholar Daniel E. Ho, writer and translator Jhumpa Lahiri, and economist and nonprofit leader Cecilia A. Conrad. An edited version of their presentations follows.

Charles F. Gammie

Charles F. Gammie is the Stanley O. Ikenberry Endowed Chair in Astronomy and in Physics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2024.

It is a joy and an honor to be here today, to be inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and to speak on behalf of Class I, the Mathematical and Physical Sciences. This weekend has instilled a sense of wonder and accomplishment at joining such a remarkable fellowship. Being admitted to the company of Euler, Gauss, Einstein, and so many others who created the intellectual landscape we inhabit today is deeply moving for me, and perhaps for you as well.

It is this sense of wonder that I’d like to talk about today. My main point is about the importance of curiosity, surprise, and the unexpected—in my life, in my discipline, and in the work represented in the Academy more generally.

I began college expecting to study math and go on to law school, maybe because I had a keen interest in history. Curiosity led me astray, however, and I found a course on Einstein’s theory of gravity so attractive that I was drawn toward the study of physics. To my great surprise, when I finished college I was headed for graduate school in astrophysics rather than law school, and my keen interest in history had been surpassed by a keen interest in a historian, who I was later fortunate to marry!

I have continued to follow my curiosity in the intervening years, and it has led me on many unexpected adventures. I still have vivid memories of the smell of metal and machine oil inside the twenty-foot horn antenna at Bell Labs, where the cosmic microwave background, the relic of the Big Bang, was discovered; seeing snow fall through headlight beams atop Mauna Kea on the Big Island of Hawaii, where telescopes study distant galaxies, planets, and black holes; and speaking with reporters at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., where the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration unveiled the first image of a black hole.

That black hole image was seen by billions of people and, in what was perhaps our collaboration’s greatest achievement, inspired Krispy Kreme to offer free orange donuts for a day!

The black hole image was more than a treat for donut eaters. It demonstrated beyond a shadow of a doubt that the massive dark objects found at the centers of galaxies, including our own Milky Way galaxy, are black holes containing the mass of millions to billions of suns. The image also set us on the road to measuring the one number other than mass that describes a black hole: its rotation rate or spin. To do this we will need to make sharper images of a black hole from a satellite in orbit around the Earth, and also make a movie of a black hole.

My colleagues and I have had great fun thinking about black holes. People around the world have had fun reading about it and looking at our images. And soon, we hope, people will have fun viewing the first movie of a black hole. But does all this have a more serious purpose?

As my Scottish grandmother once asked when I told her that I was going to study astronomy, “are there any commercial possibilities?”

This returns us to the theme of the importance of the unexpected, of surprise, and especially of curiosity-driven research. It seems to me that curiosity-driven research will continue to be important, even in a world beset by climate change, war, and the disruptive advent of intelligent machines. I will offer just a couple of reasons for the pursuit of curiosity-driven research, using astronomy as an example.

The first reason is that astronomy inspires. Astronomy inspires children, students, adults, and researchers to widen their perspective, to think about our place in the universe, and to learn to solve problems. It is an educational strategy that works. You will find former physics and astronomy students from my own University of Illinois working in almost every field of human endeavor: in agriculture, education, online commerce, public policy, finance, insurance, and energy. You will even find one of them working as a statistical expert in major league baseball. For the Houston Astros, of course.

The second reason is that curiosity-driven research is an efficient strategy for advancing human knowledge. This is a familiar argument, and there are many examples that you have probably heard before. But one connected to black holes may be new. Einstein’s theory of gravity, general relativity, developed through curiosity-driven research more than a century ago, predicted the existence of black holes. It was, much later, used to predict the characteristic donut of light seen in Event Horizon Telescope images of black holes. This same theory is also fundamentally embedded in the design of the global positioning system, or GPS, which your phone uses to determine your position, anywhere on Earth, to within a few meters.

To end on a hopeful note, I want to emphasize that the space above our heads is full of opportunity. We now know that our galaxy, the Milky Way, contains not just a hundred billion stars but also at least a hundred billion planets. Do any of these planets harbor life? I hope that within my lifetime curiosity-driven research can bring us an answer to this question and, along the way, bring us unexpected answers that can change lives for the better.

© 2025 by Charles F. Gammie

Helene Muller-Landau

Helene Muller-Landau is a Senior Scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute based in Panama and Lead Scientist of the ForestGEO Global Carbon Program. She was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2024.

Thank you to the Academy for this honor. I’m humbled to be here in such august company. I thank the many people who have shaped my path here—family, teachers, mentors, colleagues, and students.

I’m not going to talk today about any of the many wonderful scientific accomplishments. Instead I’m going to talk about scientific failures, cases where scientific “experts” and indeed the scientific community as a whole came to incorrect conclusions that led to real harms. And I ask what we as a scientific community can do to avoid such tragedies.

It’s easy to come up with many past instances when scientists got things very wrong, with grave consequences. Only a century ago, leading scientists of the day argued that top predators like wolves and hawks are vermin and should be eliminated, that schizophrenia is caused by poor mothering, that forcibly removing Native American children from their homes and communities to be raised in boarding schools would do them good.

We can look back on these errors and shake our heads at how scientists at the time got it so wrong, how much damage this caused, speculate on how they let their prejudices distort their science, congratulate ourselves on how we know so much better today, how we are better people, better scientists than they were.

But we are not without our own biases and blind spots.

So I ask, when future generations, say one hundred years hence, look back on the science of today, what errors will they see that we are blind to? How will they judge us? And when I talk about errors, I do not mean just the individual scientists who were wrong. Obviously, scientists are not gods. We make mistakes. Individual studies can be misleading. But science is supposed to be self-correcting and robust to such mistakes.

Yet within our lifetimes, not only individual scientists but the scientific community as a whole have made major mistakes with grave consequences. Forest scientists practiced complete fire suppression; the biomedical community promoted low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets; educators deemphasized phonics in reading instruction. Think about your own fields, your own experience and knowledge of policy-relevant science, and I’m sure you can all come up with many more examples.

Much has been written about the declining trust in science, especially in the United States. Blame is often placed on political polarization, on disinformation and misinformation, on bad actors. Efforts to combat this, including some by this Academy, focus on helping scientists communicate their science better, educating the public about how science works, countering misinformation. And the basic message is: the problem isn’t us scientists; it’s them, the public. And the way the press reports on science. And the bad self-interested actors like Big Tobacco and Big Oil.

Now surely these factors all play a role in the declining trust in science, and a lot of good work has been and is being done to address them. But I think we are letting ourselves—the scientific community—off the hook too easily.

Consider the life experience of a hypothetical American who has been “listening to the science” all his life.

- He switched to a low-fat diet after the surgeon general’s report came out, and for decades struggled with his weight and associated metabolic disorders. And then the scientific advice changed. He switched to a low-carb diet and lost weight.

- The Forest Service practiced complete fire suppression for decades in the national forest near his home. The fuel built up, and eventually there was a catastrophic fire that burned down his house.

- He had two kids, and when the first one was a baby, doctors said to avoid feeding babies peanuts or other potentially allergenic foods to reduce the chance of peanut allergies. So he followed that advice, even though his parents told him they had fed him and his sister peanuts early on and neither he nor his sister developed allergies. His first child, a son, developed a severe peanut allergy. By the time he had his second child, a daughter, the scientific guidance had changed to recommend early introduction of allergenic foods. He followed that advice, and his daughter never developed allergies.

- His son’s elementary school teachers followed a reading program in vogue at the time that deemphasized phonics, and the boy struggled with reading for years. By the time his daughter reached kindergarten, the school had switched to a phonics-centered program, and his daughter had no trouble with reading.

Looking back, the latest scientific advice had major detrimental effects on his health, his home, his son’s health, and his son’s educational trajectory. Is it any wonder some Americans don’t trust science or scientific advice?

Obviously, hindsight is 20/20, and we can’t blame people for not knowing then everything that we know today. But how did we end up with scientific recommendations that actually reversed prior practices and made things worse? Why did self-correction take so long, with such high casualties in the meantime? What went wrong? And where is the mea culpa from scientists? Where is the post-mortem of how this happened? The only post-mortems I know of are from the popular press. Where is the self-reflection of the scientific community on what went wrong and how we can do better in the future? Where are the lessons learned?

I think we are missing a major opportunity to do better: to improve science, to improve scientifically based policy recommendations, to improve human well-being.

We, the scientific community, have a successful model for post-mortems that we could build on. In 1999, the Institute of Medicine released a report “To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System” that revealed that 98,000 patients were dying in U.S. hospitals every year of preventable medical errors. At the time, these errors were seen either as inevitable and accepted with resignation, or as the result of a few bad apples that needed to be weeded out. Any investigation tended to focus on assigning “shame and blame.”

But that report ultimately led to a major shift in how medical errors were viewed, to the recognition of systemic problems contributing to errors, and to shifts in practice that have greatly reduced these preventable errors and deaths.

I think we owe the public, and we owe ourselves, thorough post-mortems on major failures of past scientific recommendations. What went wrong? And how can we, both individually and as a community, do better in the future? Because, if we don’t learn from our mistakes, we are doomed to repeat them. And not only will this result in a continued decline in trust in science and the influence of scientists, but more importantly, it will do actual harm.

I don’t know what we would find if we did such a post-mortem. But I have some ideas on what we might do, collectively and individually, that might help.

- Remember that the road to hell is paved with good intentions. In all these cases, including the horrific older ones, the scientists involved thought they were advancing the public good.

- Good intentions don’t make us right.

- Don’t allow a heckler’s veto and, more generally, don’t allow a “bad actor’s” veto. Reviewer comments such as “This study will be misused by evil people (Big Food, Big Oil, opposition politicians) to stymie urgently needed action on an important problem or to unjustly attack good people” should not be allowed to affect publication decisions or scientific conclusions or recommendations.

- Everything can be misused or twisted to bad ends. We need to get the science right or we risk doing more harm.

- When developing policy recommendations, seek out opposing viewpoints, and carefully consider them.

- Seek broad input from the scientific community, not just from those most inclined to speak up.

- Develop mechanisms for anonymous expert input, especially on controversial or politically hot topics. Any differences between anonymous and non-anonymous experts are a red flag.

- Look to other times and places, and if practices and recommendations differ, consider why.

- We can’t look to the future, unfortunately, but we can look to the past, and to other countries.

- Don’t overstate certainty.

- Don’t rush to a false and premature consensus.

- Don’t suppress dissent out of fear that a known lack of consensus among scientists might be misused by opponents of the policy recommendations (that would be a bad actor’s veto).

Those are things we might do as a community. As to what we can do as individual scientists:

- Don’t be overconfident. Be humble. There is so much we still do not know.

- Don’t tie up your ego with being right.

- Don’t personally attack people who disagree with your position.

- Don’t invoke the bad actor’s veto to try to suppress views you disagree with.

- Don’t remain silent when you thoughtfully disagree with the prevailing viewpoint, or when you see problems with the process, like suppression of dissent. Don’t self-censor. Be brave.

- Finally, be less concerned about the judgment of your peers and the public today. Think instead of the judgment of future generations. How will future scientists, future people, judge us?

© 2025 by Helene Muller-Landau

Daniel E. Ho

Daniel E. Ho is the William Benjamin Scott and Luna M. Scott Professor of Law, Professor of Political Science, Professor of Computer Science (by courtesy), Senior Fellow at Stanford’s Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, and Senior Fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research at Stanford University. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2024.

It is such an honor to be here. Being inducted into this venerable institution and filmed here today indeed fulfills the dream of a lifetime: to star in a film associated with the name George Clooney! In all seriousness, it is hard for me to convey how grateful and honored I am to be at these festivities today.

I grew up in a small town in Germany. By virtue of a generation displaced by the Chinese Civil War and World War II, my parents found themselves in a strange country in their twenties. I saw a generation of Germans question the choices of their parents. And I remember as a young boy seeing firecrackers on the streets when the Berlin Wall came tumbling down.

That childhood left me with an indelible impression: our social institutions are fragile. And I’ve spent much of my adult life trying to wrestle with that fact. Trust, and public trust, is earned in drops and lost in buckets.

Those indelible impressions are what drew me to law and the social sciences. Some see a sharp juxtaposition between the two. Law is about advocacy and how things should be. The social sciences are about observation and how things are.

But the world’s most wicked problems are social problems, which don’t come packaged neatly in disciplinary trappings. Despite the fact that the American Academy of Arts and Sciences might classify us neatly into different Classes and Sections by discipline, there is deep value and urgency in engaging across these boundaries, just as we are today.

So much can go wrong if we don’t. I’m reminded of a faculty lunch between two colleagues: one an international human rights lawyer and the other an intellectual property scholar. They spent several minutes engaged in a vigorous debate about pirates. But only five minutes into this debate did they realize that one colleague was talking about Somali pirates and the other one was talking about software pirates. I think they came to more agreement after clearing that up.

Let me offer three examples of how our institutions—and the urgency to strengthen democratic institutions—need that broader form of engagement across boundaries and with the social sciences.

Example One. The county I live in, Santa Clara County, was the first in the country to see the trajectory of the pandemic and issue a shelter-in-place order, which was informed by the emerging infectious disease science. But within a matter of weeks, the social dimensions of COVID-19 hit with a vengeance. Although Latinx individuals make up about 25 percent of the county’s population, they accounted for more than 50 percent of the COVID-19 cases. In order to tackle dramatic racial disparities, the classic public health toolkit had to grapple with social disparities. To allocate scarce testing resources, a conventional strategy favored by infectious disease experts was to go after household members of people who tested positive. But the precise worry was about blind spots in testing coverage. We showed in one intervention that the social knowledge of community-based health workers (promotoras de salud) and simple insights from machine learning doubled or tripled the effectiveness of the conventional strategy. Public health could not afford to turn a blind eye to the social disparities of disease.

Example Two. One of the fiercest debates of our time is around the governance of artificial intelligence, how to harness its potential for good while addressing its potential for bias, privacy violations, worker displacement, disinformation, and the like. Conventionally, AI has been evaluated via technical performance benchmarks. But as AI moves into the real world, those computer science benchmarks are proving woefully insufficient. The fear is not about the technical property alone; it is about the human-machine interaction, which requires the science of human decision-making. The funny thing about humans is that they can ignore, overrule, or overrely on algorithmic tools. Humans love automated music recommendations, but hate medical ones. Some judges rely too much on criminal risk assessment scores and others find them a waste of time. In recognition of the need to treat the governance of AI as a sociotechnical challenge, the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI and Stanford RegLab bring together a wider range of disciplinary perspectives and communities to ensure that the future of AI centers human values and social impact.

Example Three. What is the future of government in light of existential challenges to democracy? Public trust is at an all-time low. And part of the blame is that government programs often don’t work very well. It is in the basic citizen-state interactions—the payment of an unemployment check and filing of a tax refund—where public trust is earned or lost. For decades, the Supreme Court has emphasized the need for accuracy in these interactions: in benefits decisions for veterans, immigrants, and the disabled. Emerging technology may help increase accuracy in government decision-making. But over the course of the twentieth century, the Supreme Court came to neglect equally important values, like dignity and equality, in favor of accuracy as the lynchpin of procedural due process. A program with perfect accuracy may still fail its most basic democratic goal. The wrong move would be to use technology to wholesale skip hearings in the name of accuracy and efficiency. As one veteran noted to a judge, “Judge, I know I’m going to lose, but I just want to be heard.” We can treat government programs like an engineering challenge, but as the social sciences teach us, process—and dignity—matters.

Each of these simple examples teaches the same basic lesson: to address wicked problems requires engagement across boundaries. Working to help solve society’s toughest problems leads us to a more engaged social science, one that moves from dispassionate observation to engagement, collaboration, and, yes, intervention.

Science is social, and we cannot tackle the most urgent challenges of the day without the social sciences.

© 2025 by Daniel E. Ho

Jhumpa Lahiri

Jhumpa Lahiri, a bilingual writer and translator, is the Millicent C. McIntosh Professor of English and Director of Creative Writing at Barnard College, Columbia University. She was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2024.

As this year’s Class IV speaker, I represent the Humanties and Arts: I am part of this group, and our group forms a part of the Academy as a whole. Thanks to this ceremony, my fellow inductees and I will begin to take part in the Academy’s activities. Being a part, taking part: these are synonyms for being a member, participating, contributing to a greater good.

In recent years I have been pondering the significance of parts and wholes in relation to one of my current projects: an English translation of The Metamorphoses, Ovid’s opus magnum, composed in Latin between about 2 and 8 CE. I am undertaking this translation with a former colleague at Princeton, classicist Yelena Baraz. Given its collaborative nature, our translation is partly hers, partly mine.

It was in a college Latin class that I first encountered Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a deeply variegated text describing approximately 250 accounts of human transformation. When Ovidian transformation occurs, the new state of being, whether animate or inanimate, tends to retain certain aspects of the previous self. Thus the Myrmydons, in Book 7, are ant-born soldiers who retain their frugal nature and ability to toil. Ovid reminds us that we all contain the seeds of change—sometimes radical change—within us.

Why did this work speak to me in my twenties? Why does it guide me still? Perhaps because I recognize my own hybrid identity in its weave. From childhood I lived partly in one language, partly in another. My upbringing had two landscapes, two idioms, two traditions, a juxtaposition of values. I wrote to explore different parts of me. Over the years, my creative and intellectual life has broken down into further parts: there is the writer in me, the academic, the translator, the part that writes in English, the part that writes in Italian. This double register correlates to how I was raised, by parents partly in the here and now, partly attuned to a reality unfolding on the other side of the world.

Borders, partitions, limits: these are terms in English to signify that which separates and divides. Italo Calvino, in his introduction to an Italian edition of the Metamorphoses, observes that Ovid is always problematizing borders and frontiers.1 But Ovidian borders, Calvino notes, are porous, serving to both demarcate and merge separate identities. Indeed, though the poem is segmented structurally and narratively, its essence is fluid, rich with slippage and ambiguity.

At the start of the poem, Ovid describes Creation, a state of affairs in which there are no parts. Here is our translation-in-progress:

Before sea and lands, and sky that covers all

nature showed one face across the whole globe,

called chaos: a rough, unprocessed mass,

merely an inert clump heaped together in one spot:

discordant seeds of disparate matter.2

The word “all” (omnia in Latin) appears in the first line of this passage, while the final line contains “disparate” (in the Latin, non bene iunctarum, meaning not well-joined). The original universe, lacking limits, lacking places, is called chaos, a word and concept that come from ancient Greek, meaning void, which comes to mean disorder.

My gravitation toward reading stories, which led me to writing them, was an attempt to organize the incoherence of life. Books were a parenthesis; stories, a refuge from my not well-joined self. The more I thought about literature, the more I realized that it was an open-ended, partial conversation. Artists and writers don’t strive to find solutions or arrive at incontrovertible truths. In questioning and confronting facets of the human condition, they may modify our perspective. Someone—Picasso—exaggerates the partial nature of the human face, altering the way we see each other and ourselves. Literature, too, thrives on detail. I have never forgotten the description of poor Narcissus’ chest in Book 3 of the Metamorphoses after he beats himself, as the image of his beloved, another part of himself, dissolves into water:

much like those apples that are partly white,

partly red as well, or the way grapes in

multi-hued clusters, still unripe, acquire a purple shade.

Like some apples and grapes, much of nature is hybrid in aspect. And yet, being composed of different parts, being biracial or bicultural or bilingual, being someone who has chosen or been forced to cross borders, has never been easy. In Greek mythology, hybrid creatures were tantamount to monsters. Those of us who house more than one self in our souls may feel like imposters every time a boundary is drawn, every time our commingled origins are called into question. We cannot claim a mother tongue or pinpoint where we are from; we fear that our various parts don’t amount to an authentic whole. A piecemeal identity, something Ovid spotlights in antiquity, something Primo Levi reiterates when he calls man as a centaur, “a tangle of flesh and mind,” threatens a world preoccupied by borders, populist movements, paradigms of normativity, and ideologies of the nation-state.

You don’t need me to tell you that the humanities are in peril, that people read less, that foreign language departments are disappearing. These changes trouble me and some members of my group; like climate change, they will have grave consequences for our world. The poet Patrizia Cavalli wrote a book called My poems can’t change the world. She’s right, they can’t; but they might change a reader, and each reader is part of the world. That is why some of us continue to make poetry, teach it, keep it relevant. Art and poetry can reframe the world by centering the peripheral, lingering over what goes unnoticed. But a poem, written in any given language, only reaches part of its potential readers. Translation accompanies the text across its natural limits, altering language so that readers can comprehend written words from other cultures, and recognize the other in themselves. Translation, the most humanistic of endeavors, is one in which artificial intelligence can never play a relevant part.

Ma phaleshou kadachana. My father taught me these three Sanskrit words from the Bhagavad Gita when I was young. They mean: Do your work, but don’t expect the fruits of your actions. I work with words, reading and forming and transforming them, with no other purpose or mission. My father began the American part of his life’s journey here in Cambridge, working as a librarian at MIT; here sprang the American strand of my identity. We lived behind Inman Square, my mother walked with me up Mass Avenue to play in Harvard yard, and when we moved to Rhode Island, she brought me back to Sanders Theatre to appreciate classical Indian music concerts played upon this stage.

In poetry, there is a rhetorical device called synecdoche that refers to the play between parts and wholes. In ancient Greek, synecdoche means to understand more than one thing at once. Ovid uses synecdoche to describe the sea according to its green-blue shade, or a wing by virtue of its feathers. I recall my Cambridge origins because they form part of my metamorphic beginnings. They link a previous part of me to the here and now, and contribute to the emotion of standing before you today.

© 2025 by Jhumpa Lahiri

Cecilia A. Conrad

Cecilia A. Conrad is a Senior Advisor at the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and CEO of Lever for Change, a nonprofit that helps donors find high-impact philanthropic opportunities. She was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2024.

My dad was born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where he started college at Southern University, an HBCU, at the age of sixteen. In his junior year he was drafted for World War II, but then something extraordinary happened, especially in 1940s Jim Crow Louisiana. My dad took a special science and math exam, and based on his performance on that test the Army sent him to Stanford instead of to combat, and then paid for his first year of medical school at Meharry. Southern University clearly provided a solid education, but my father described his arrival in Palo Alto as life-changing. He talked about the thrill of sitting on the first floor of a movie house in seats with arm rests instead of in a segregated balcony. He expressed gratitude to his white roommate who invited him to spend Thanksgiving with his Los Angeles family. Doors that had been closed were now open.

He spent the rest of his life pushing doors open for others. He was a surgeon, but also a public servant. As the first Black man elected to the Dallas School Board, he created a free breakfast program, pushed for bilingual education, demanded equal pay for Black and white teachers, kept pregnant teens in classrooms—and the list goes on. Clearly that open door, that opportunity, benefited not only my dad but society writ large.

I am my father’s daughter. Like him, I benefited from formerly closed doors that were opened by the concerted efforts of his generation. An early affirmative action initiative created as part of a historic settlement of the EEOC v. AT&T case funded a college internship at Bell Labs and my graduate education. And like my dad, a central goal in my career has been to open doors. As a professor and academic leader, I’ve pushed for access and inclusion across disciplines, but most especially in my own discipline of economics.

When I came to philanthropy eleven years ago, I was surprised that there were so many closed doors. An overwhelming percentage of foundations, over 70 percent, do not accept unsolicited requests for funding. Grant opportunities are mostly by invitation only, a likely contributor to the big disparities in revenue and assets between white-led and Black-led early-stage nonprofits. I was also surprised at how little focus there was on solving problems as compared to mitigating the symptoms of problems. With average grants of under $50,000 and a duration of eighteen months, we’re unlikely to make significant headway on critical problems. So when then–MacArthur President Julia Stasch asked, “What if we opened things up?” I leapt at the chance to create a new model for philanthropic giving.

Our first experiment was 100&Change, an open call grant competition that asked problem-solvers around the world, “How would you use $100 million to make significant headway in solving a problem?” The first grantee of 100&Change is an early childhood intervention in the Syrian refugee region of Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, and Syria, led by Sesame Workshop and the International Rescue Committee. At year five, this intervention has improved children’s learning and their caregivers’ well-being by delivering customized educational content, including a new local version of Sesame Street that reaches 240 million children.

Our model is open—not only because any organization can apply, but also because we welcome diverse ideas and perspectives. We are open to listening to independent voices and relying on their advice to guide donor decisions about what to fund. We crowdsource multiple forms of expertise to help donors find where their dollars might have the greatest impact. And by facilitating large multiyear grants, we empower nonprofits and social entrepreneurs most proximate to the issues to identify the critical problems to be solved and implement the solutions that work.

Since that first experiment, Lever for Change has designed and managed over a dozen open calls on behalf of individual donors and foundations and facilitated over $2 billion in gifts. We have learned that openness finds organizations not on the radar of most foundations and major donors, leads to greater equity in grantmaking, uncovers unexpected collaborations like Sesame Street and the International Rescue Committee, and inspires creative, sustainable, and feasible approaches to solving problems. These lessons apply beyond philanthropy. Openness requires both an open door and a receptiveness to new perspectives, to reasoned opinions not your own. It requires humility and acknowledgment that no matter the wealth one has accumulated, or the accolades and validation one might receive, including election to this Academy, others might have better ideas.

I am struggling with the humility part this afternoon. I’ve heard a lot of humility among my fellow inductees, but I will admit I’m feeling pretty good right now. But whenever I get a little out of line, I have a voice in the back of my head that belongs to my mother-in-law. My mother-in-law, a brilliant Bajan woman, helped make it possible for me to be here today because she took care of my son when he was young. We didn’t always see eye to eye. One day in a fit of peeve she said to me, “You may have a PhD, but you don’t know everything.” So it is with deep humility and Edith’s voice in my ear that I look forward to signing this book and joining this historic organization.

© 2025 by Cecilia A. Conrad

To view or listen to the presentations, visit the Academy’s website.