The History of the Academy

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences, established in 1780, is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States.

The story of the Academy deserves telling. Believing from the beginning that the discovery and communication of new knowledge was its first obligation, the Academy supported and honored theoretical research even as it recognized the worth of more practical studies, By accepting very early the idea that the nation could be served best by an institution that avoided every form of narrow partisanship, the founders sought to involve individuals whose interests were diverse, who espoused no single philosophy, pursued no one profession. READ MORE

The following timeline represents key milestones over the three centuries of the American Academy and its “pursuit of useful knowledge.”

In 1780, sixty-two individuals—clergymen and merchants, scholars and physicians, farmers and public leaders—signed their names to the Charter of the American Academy. Along with John Adams and James Bowdoin, the founders included Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and Robert Treat Paine. The charter directed the Academy’s programs toward both the development of knowledge—historical, natural, physical, and medical—and its applications for the improvement of society. Shortly after ratification, the Academy held its first meeting on May 30 in the Philosophical Chamber at Harvard.

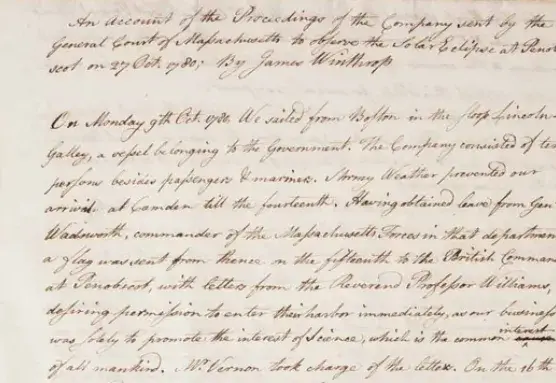

At its third meeting the Academy voted to join with Harvard in sponsoring an expedition to Penobscot Bay in present-day Maine to observe a solar eclipse. The Massachusetts State Board of War provided a ship and arranged for the safe passage through the British lines. The expedition, headed by Harvard Professor Samuel Williams, left Boston on October 9. Although they failed to locate in a place under totality, Williams’ observations did include a view of what some years later was called Baily’s beads or a view of the sunlight shining through the valleys of the moon.

Read more in The Bulletin (Winter 2004), p. 47

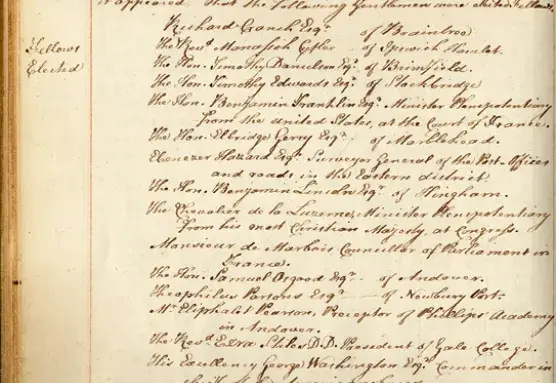

New members selected by the Academy in 1781 included Benjamin Franklin and George Washington, as well as several Foreign Honorary Members. Since that time, over 13,000 individuals have accepted Academy membership, including Thomas Jefferson, John James Audubon, Joseph Henry, Washington Irving, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Willa Cather, Jonas Salk, Eudora Welty, and Edward K. (Duke) Ellington. Foreign Honorary Members have included Leonhard Euler, the Marquis de Lafayette, Alexander von Humboldt, Charles Darwin, Albert Einstein, T. S. Eliot, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Nelson Mandela.

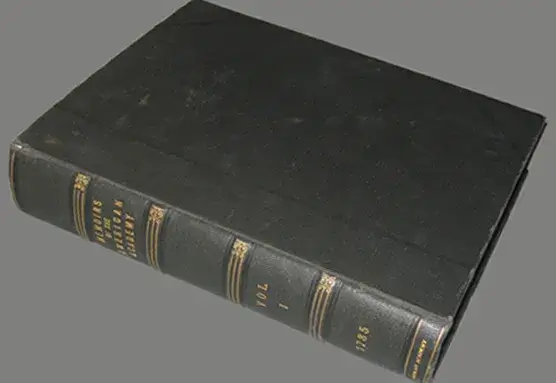

The first volume of the Memoirs appeared in 1786, containing some fifty-four papers. The title page gave 1785 as the publication date, but various issues delayed its appearance until the following year. Editorial supervision was exercised by three committees on mathematical, physical, and medical topics, and the volume reflected these divisions. Emphasis was on practical knowledge and included ten papers by authors who were not members of the Academy. Papers in the “Physical” section (including natural philosophy, natural history, and technological devices and processes) formed the majority of the volume.

At the Academy's annual meeting in 1839, the Rumford Committee reported that chemist Robert Hare of Philadelphia had been selected as the first recipient of the Rumford Prize. In a letter of July 12, 1796, Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford, had offered the Academy $5,000 to establish an award for work in heat and light. To be conferred every other year, the prize was to take the form of two medals (gold and silver) whose value equaled the $300 income from the fund. Hare, elected to the Academy as an Associate Fellow in 1824, was awarded the prize for for his development of the oxy-hydrogen blowpipe around 1820. List of recipients since 1839

A protracted debate within the Academy over Darwin’s Origin of Species began with a paper on Japanese flora presented by Asa Gray, leading to an exchange between Louis Agassiz and William Barton Rogers, representing, respectively, positions opposed to and favoring Darwin’s views on evolution and natural selection. Read more

Maria Mitchell, an astronomer from Nantucket, was elected to the Academy at the annual meeting of 1848. Mitchell had discovered a new comet the previous October, an effort which ultimately earned her the King of Denmark’s Comet Medal in December 1848. Her father William was also an astronomer and had been elected to the Academy in 1842; her younger brother Henry would later become a member in 1866. However, nearly a century would pass before more women were elected in 1943.

See acceptance letters from women elected after Mitchell

The centennial of the Academy was observed with a ceremonial meeting in Old South Church and a reception in the Academy’s hall at the Boston Athenaeum. Attendees included delegates from American and foreign learned societies. Speakers included former Academy President Asa Gray, Harvard President Charles Eliot, and Robert C. Winthrop, great-grandson of James Bowdoin, filled in for Academy President Charles Francis Adams for the keynote address. The festivities also included a poem by Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., an ode which drew upon the history contained with the Academy’s Memoirs: “See on this opening page the names renowned, Tombed in these records on our dusty shelves...”

From 1780 until 1904, the Academy did not have a permanent headquarters; instead it held meetings at Harvard and the Boston Athenaeum, among others, and even occasionally at the homes of Academy members. A building was purchased at 28 Newbury Street in 1904, to serve as the Academy’s own home, and a six-story fireproof annex for the library was added. The first meeting was held in the new facilities on January 10, 1906. The adjacent property was purchased soon after and a much larger edifice—funded by former Academy president Alexander Agassiz—opened for the Academy’s use in May 1912. The Academy remained at the Newbury Street location until 1955.

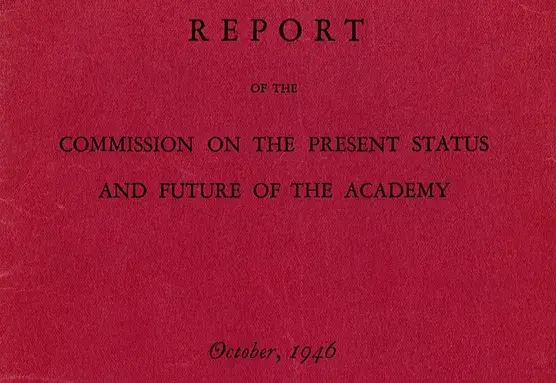

The report of the Commission on the Present Status and Future of the Academy, appointed by President Howard Mumford Jones in 1945 and chaired by Kirtley F. Mather, was presented to the Academy membership. Among the points and recommendations was the promotion of a greater role of the Academy in formulating opinion on public policy issues, the establishment of a standing nominating committee for all membership categories, the appointment of an executive officer, and the sale of the library. The report marked a paradigm shift in the mission and goals of the Academy.

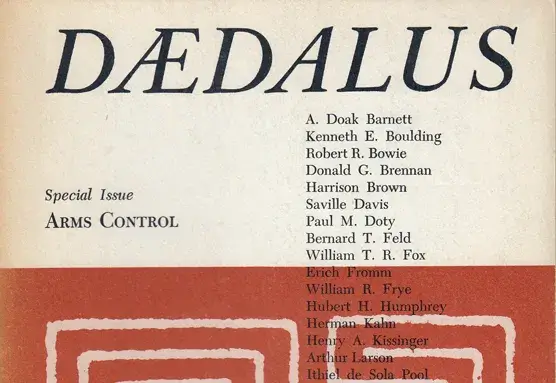

In 1955, the Academy launched its journal Daedalus, reflecting its postwar commitment to a broader intellectual and socially-oriented program. The journal, originally conceived as a successor to the Proceedings, became a quarterly in 1958. Around the same time, arms control emerged as a signature concern of the Academy as scientists, social scientists, and humanists grappled with the social and political dimensions of scientific change. Daedalus established itself as a significant scholarly journal with its Fall 1960 issue on Arms Control, coinciding with the election of John F. Kennedy to the American presidency and the deepening of the Cold War.

After renting office and meeting space at the Brandegee Estate in Brookline since moving from Newbury Street in 1955, the Academy made arrangements with Harvard University to build a new headquarters near the Divinity School. Polaroid founder and former Academy president Edwin Land donated the funds to build a new “House of the Mind” and endow its maintenance. Designed by Kallmann, McKinnell, and Wood, the new building incorporates classic architectural design as well as natural elements from the surrounding woods. The dedication of the Academy’s new Cambridge home took place on May 14, followed by a two-day celebration of the Academy’s bicentennial.