Higher Education in the Twenty-First Century: What’s the Mission?

The “mission” of a sector of society can encompass a range of possibilities. Sometimes, the mission is broad. Sometimes, it is narrow. Sometimes constant, sometimes changing. Missions serve as guideposts. They articulate a central purpose or goal, which should help to structure decisions and actions: as examples, who should be served, exactly what should be done, how the work is carried out, which measures can determine whether the mission is actually being realized, and, if not, how a course can and should be corrected.

Whole sectors or spheres can have missions. Broadly speaking, the health care sector works to provide physical and mental well-being for individuals and society. Within the sector, one encounters a range of professionals (researchers, nurses, doctors, pharmacists) as well as settings (hospitals, offices, laboratories, clinics). Some personnel are focused on a particular area, illness, or demographic group, while others are generalists. Some institutions are private; others are public; a few are composite. The direction or foci may shift as the needs of individuals change, or societies evolve, or as the leadership across organizations changes. But the fundamental purpose of restoring or maintaining health is not—and should not be—obscured or lost.

This might seem straightforward so far.

However, as we turn to the sector of higher education, the concept of mission becomes more vexed. As early as the sixteenth century, the Jesuits used education as a way of defining the word mission—to educate and spread the word of Christ. But as colleges and eventually universities spread throughout the world, the mission broadened from religious purposes—for example, preparing young people for work in secular professions, training scholars in the sciences and other disciplines, or giving members of certain demographic groups an opportunity to meet peers, as well as individuals from other, more diverse backgrounds.1

In the United States, the missions of the earliest institutions of higher education were rooted, at least in part, in Christian (Protestant) values. Universities sought to respond to a need for a learned clergy; indeed, roughly half of Harvard College’s earliest graduates went on to become ministers. Over time, however, the religious mission of American universities began to fade. Modeled after German institutions that focused on training students for specific professions, higher education increasingly centered on preparing citizens for work and contributing to society, notably in science and technology. In these ways, the sector broadened its mission to meet new needs. By the nineteenth century, universities began to feature a plethora of professional schools, along with a broader, more secular curriculum. And as the twentieth century unfolded, increased funding for public education attracted more citizens with varied backgrounds, interests, and aspirations.2

Today, as evidenced in this volume of Dædalus, tertiary institutions all over the globe exist for a range of purposes—to provide professional training, to teach and conduct research in an ever-expanding array of disciplines, to educate underserved populations, to focus explicitly on globalization, climate change, the arts, and/or to cultivate specific political viewpoints and orientations. Indeed, many of the institutions have different stated missions. Even within one country or region, institutions of higher learning may be “all over the map.”

Like health care organizations, educational institutions within and across countries may not have precisely the same mission. But we contend that, at the very least, each institution and its stakeholders should have clarity about its own central mission.

Our own extensive research focused on liberal arts and sciences (hereafter, “liberal arts”) at universities in the United States provides a troubling perspective, one that might come to pass soon for others around the world. We have observed and documented a disturbing lack of consensus among key stakeholders about the purpose(s) of higher education, both within single institutions and across the sector.

Based on in-depth interviews of more than two thousand individuals across ten disparate campuses, we have found striking dissociations. Most notable, while students, parents, alums, and trustees view university primarily as the necessary path toward a future job, most faculty and administrators believe that the university experience is an opportunity for intellectual transformation, the time and place to prepare students for lifelong learning and citizenship.

We suggest two reasons for this major misalignment.

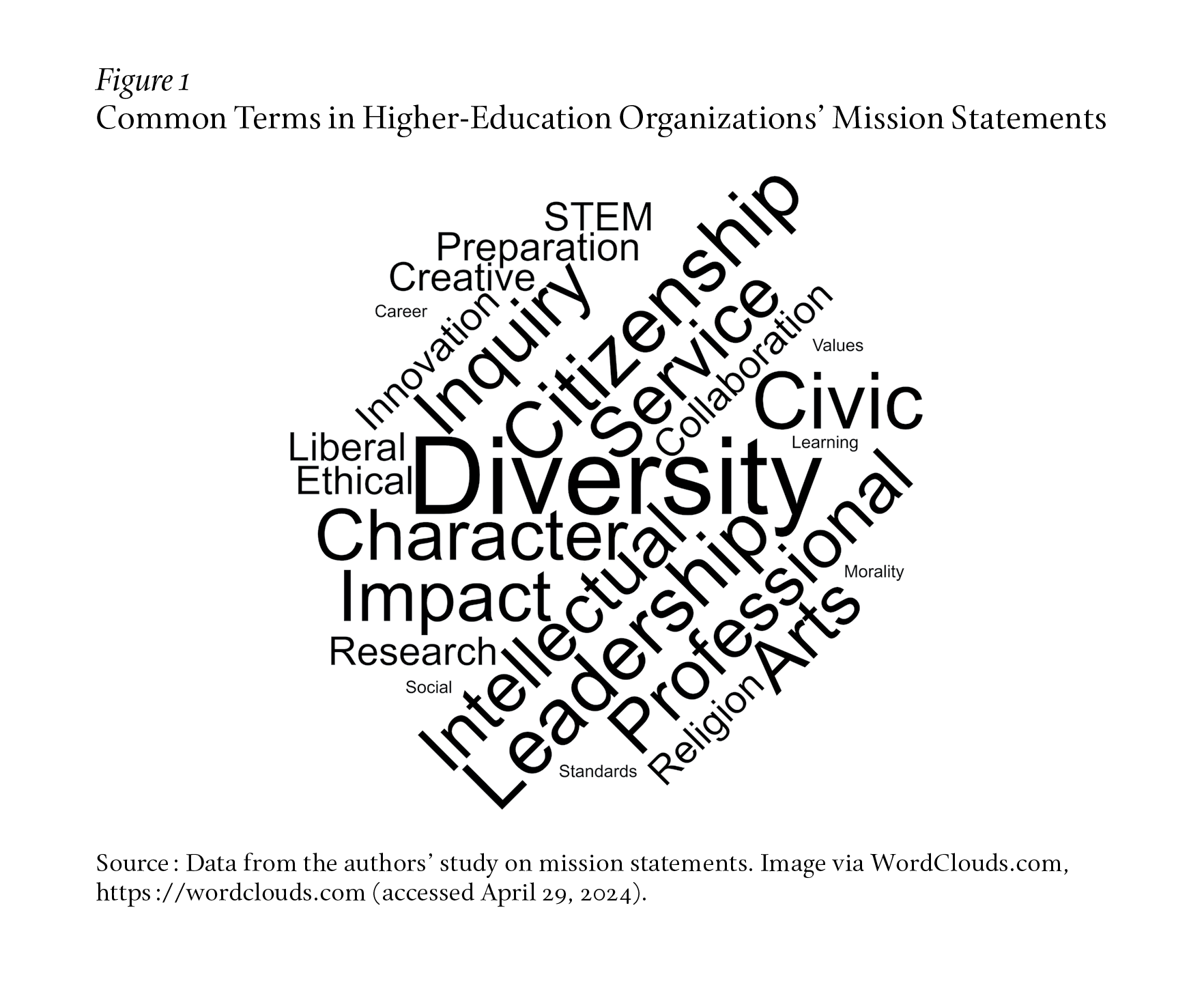

One explanation is what we call mission sprawl—the promotion of multiple missions on a single campus. Rather than a set of focused goals, we find that institutions that invoke the liberal arts attempt to pursue a myriad of goals for too many disparate groups of people, thus obscuring their own primary reason(s) for existing. As examples, in their mission statements, many institutions of higher learning trumpet keywords such as leadership, globalization, career preparation, and social and ethical services. As shown in the word cloud in Figure 1, the list goes on! While an entire sector may be able to address this gaggle of promises, it is difficult—indeed impossible—for a single institution to take this all on, in addition to intellectual development. In an effort to please its customers, a vast number of institutions of higher learning have lost a sense of the who, what, where, and why, as each relates to their mission.

A second explanation for these misalignments among stakeholders involves universities that not only try to do too much, but also appear to be conflicted about what they are trying to do. Sometimes, single institutions promote explicit missions, clear and accessible statements of intent often found on their website and in their brochures, alongside implicit missions, underlying messages that all too often conflict with what is stated publicly. These inconsistencies and conflicts are signaled by placement of buildings on campus, decisions about securing and allocation of resources, and/or the ways in which “success” is publicly defined (for example, by employment statistics and salaries of graduating students).

Our own university exemplifies this tension. Harvard College (for undergraduates) has long promoted Veritas, or truth, as its motto and on its logo (the Veritas shield). However, this word does not appear in the official mission statement (nor does it appear in the mission statements of any of Harvard’s other graduate and professional schools). If you talk with any Harvard student about his or her college experience, rarely, if at all, would you hear the word “truth,” nor would you likely hear it from a parent or a member of one of the governing bodies. It is fair to say that at this institution, “truth” is overlooked, or even, taken for granted.3 Further, as recent events have documented, various constituencies have strikingly different aspirations.4

In what follows, we place the mission of higher education under a microscope. Specifically, we identify four key dimensions of a mission for higher education: audience, content, place, and intended impact. One might call this a journalistic or interrogative approach, an attempt to gather the key parts of a school’s story—the who, what, where, and why we mentioned above—with the ultimate goal of helping individual institutions, as well as the overall sector, to achieve clarity on missions in general.

The institutions described in this volume provide illustrative examples of how one might consider missions. While it may be easy to answer just one of these questions (that is, focusing entirely on “who?” or “why?”), a more challenging task for leaders in higher education would be to identify where their institution lies along all of these dimensions. If institutions of higher education can answer these four questions, we believe they will be well equipped to align stakeholders around their priorities and to hold themselves accountable to their goals. But identifying and articulating a clear mission is just the first step. It is also important to consider how to demonstrate and measure progress toward achieving it, as well as identifying barriers and attempting to remove them.

Like any business trying to understand its customers or clients, institutions of higher education cannot realize any sort of goal for their students without a deep understanding of who is on campus. Indeed, most universities include a word in their mission statement about an intended audience—a group of individuals that the institution aims to serve. This dimension of mission is crucial, not only in guiding students who are making decisions about where to matriculate, but also for universities as they think about how to address their population’s specific desires and needs.

In the United States, a number of institutions define their audience in terms of a particular demographic or geographic group. Historically Black colleges and universities, women’s colleges, and Hispanic serving institutions are clear examples of institutions that have an explicitly stated mission to serve students of a particular identity. For this type of school, the audience is the defining or distinctive feature of the mission, a characteristic that sets it apart from other institutions of the same size and selectivity level.

Serving a particular target audience can also be a driving force for many schools around the world. In some cases, entire universities are founded on the premise that they will cater to a specific population or demographic group. Sometimes, these are populations facing societal barriers, such as unequal access to higher education and/or to positions of leadership.

Take the example of the Asian University for Women (AUW), a private university located in Bangladesh. As described by Kamal Ahmad, AUW is designed to serve female students in different parts of Asia who would not otherwise have access to an undergraduate degree.5 Founded as an antidote to gender-based discrimination in many parts of Asia, AUW’s mission focuses on empowering women who have been economically or socially marginalized by society. In order to align its audience with its goal of promoting intercultural understanding, AUW recruits students who demonstrate particular characteristics in their application—for example, tolerance and a desire to combat injustice. While the school is still meant to serve an international student body and has now reached women from seventeen countries, AUW homes in on an audience that is more narrowly defined than that at most other institutions.

Alternatively, other institutions take a deliberately wide-ranging approach to their audience, seeking students from a multitude of ethnicities, socioeconomic levels, and/or geographic regions. A textbook case is New York University Abu Dhabi (NYUAD), a collaboration between NYU and the Emirate of Abu Dhabi. A liberal arts university, NYUAD is part of NYU’s global network of schools and one of its three degree-granting campuses.

In her case study, Mariët Westermann describes how NYUAD’s undergraduate student body has been designed to be quintessentially international, representing students from one hundred twenty-five countries.6 While Emerati citizens make up more than one-fifth of the student body, the overall student population is meant to represent a wide range of nationalities, languages, and ethnicities, with no majority group. As with AUW, NYUAD’s admissions officers look for certain qualities in prospective students that align with the school’s broader goals, such as a desire to learn alongside individuals from different countries who carry differing backgrounds and opinions.

The school’s focus on attracting an international audience is an important piece of NYUAD’s broader goal of educating global citizens and fostering intercultural understanding. Despite the school’s distinctively international audience, other dimensions of the school’s mission, such as its particular location, have come to the forefront of public discourse. The decision to place the institution in a region with a difficult history of human rights has long proved contentious among some faculty members and students at NYU’s home campus.7 Though the school has assured these parties that NYUAD will maintain the same level of academic freedom that exists in New York City, this is a case in which different dimensions of missions have the potential to clash or diverge. What does it mean for such an internationally diverse audience to study and take courses in a country that places constraints on freedom of academic expression? This factor signals possible tension between the school’s audience, the who, and the content that is allowed, the what.

In addition to audience, a mission might also refer to the content, or subject matter, an institution focuses on. For some institutions, a content-centered mission may revolve around a particular educational program or set of courses. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology focuses on educating students in science and technology. St. John’s College, which contains campuses in both Annapolis, Maryland, and Santa Fe, New Mexico, is best known for its distinctive curriculum focused on great books. Indeed, at the center of many of the innovations described in this volume is the curriculum—crafted and shaped to meet identified needs pertaining to specific knowledge and/or skills, economies, and political contexts.

The recently launched London Interdisciplinary School (LIS) foregrounds a mission that is driven by its innovative curriculum and pedagogy. The school addresses a seeming shortcoming in the UK higher-education system—a lack of courses that cut across disciplines and a discrepancy between what students are learning in the classroom and the problems they might wish to address in their future careers. As its name signifies, this school embraces a deliberately interdisciplinary approach to teaching and learning, one that pushes students to explore issues in technology, climate change, and other contemporary problems from a variety of angles. Notably, the institution distinguishes itself from schools with a liberal arts mission by emphasizing practices of integration and synthesis. According to Carl Gombrich and Amelia Peterson, students at LIS learn how to make the fields “speak to each other.”8 Whether graduates will ultimately pursue distinctive careers or do so in innovative ways remains to be determined.

Minerva University is another example of a school that is driven by a distinctive general education program. Like The London Interdisciplinary School, Minerva University was designed with the goal of preparing students to address and perhaps contribute to the solution of complex contemporary global problems. As described by Teri A. Cannon and Stephen M. Kosslyn, Minerva’s curriculum addresses this goal not only by exposing students to a variety of academic areas, but also through a strong focus on the development of particular skills and capacities.9 Minerva’s courses aim to provide students with cognitive tools, such as “habits of mind”—critical thinking techniques that become internalized over time. So far, its graduates are an impressive lot. Time will tell whether Minerva can catalyze other such educational entities.

In considering the question of what, course offerings and curricula are not the only answers. Many institutions of higher education—including some with religious underpinnings—center on the dissemination of particular values, principles, and beliefs. What Isak Frumin and Daria Platonova describe as the socialist model of education was founded with the explicit goal of shaping a “new Soviet person.”10

In the wake of Soviet nation-building in much of the twentieth century, higher education was meant to produce individuals with a deep understanding of Marxism as well as a commitment to the collective state good. Although values-based (or “class-based”) education was a core pillar of Soviet education, it can also be found to varying degrees in other models of higher education. As Frumin and Platonova note, a focus on character development—or what is sometimes now referred to as “formative education”—has grown in popularity around the world.

Universities will also be shaped by the location in which learning is taking place: the where. In most cases, a university will operate statically in its home country, the region in which the school was conceived. In other cases, universities may intentionally operate outside of their home country, providing students with opportunities to learn in new cultural, political, and economic contexts—ones connected organically and organizationally, or set up on an ad hoc basis.

Consider the case of Northwestern University Qatar (NU-Q). For this institution, geographic location is a paramount part of the mission. As described by Marwan M. Kraidy, the campus is a part of Education City in Doha, Qatar, a multicultural city with a large number of expatriates.11 Northwestern’s decision to form a partnership in this region was deliberate; the school has a specific mission of developing research and teaching capacity in the Global South, a phrase that refers to economically disadvantaged nations within the Middle East, Latin America, Asia, and Africa. Furthermore, NU-Q views the Global South not as a geographic region but as an “intellectual space”—an area in which to develop scholarship that may well be distinct from that of the West. This commitment to the Global South may show up in other dimensions of its mission. For instance, the curriculum intentionally features authors from Arab, African, and Asian countries.

Notably, NU-Q enjoys support from its host country in carrying out its mission. The project grew out of a partnership between Northwestern University and the Qatar Foundation for Education, Science and Community Development. As demonstrated earlier by the case of NYUAD, however, a school’s values and aims for students can sharply conflict with the agenda of those in power in the region. Additionally, what it means to serve the “Global South” remains unclear—as does how that constituency relates to BRICS.12 The degree of economic development or opposition to Western developed or democratic societies and values needs to be clarified.

A stark example of these challenges is Hungary’s recently shuttered Central European University (CEU). As described by Michael Ignatieff and Ágota Révész in separate contributions, CEU was Hungary’s last independent university in Budapest.13 Founded and funded by Hungarian American philanthropist George Soros, who sought to create a top-tier research university that could serve as a “hub” for students in the Central-Eastern European region, CEU was designed to be a center that would promote critical thinking on complicated issues and foreground the values of an open society.

Despite the university’s laudable reputation in Europe and in the world, the institution was ultimately shut down by Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. An autocratic leader, Orbán saw the institution as a threat to Hungarian national sovereignty and perhaps to his own increasingly authoritarian rule. This governance decision, which sparked large protests in Budapest, demonstrates the push and pull that can emerge between an institution’s locale, on the one hand, and defining aspects of missions for liberal education, such as the principle of academic freedom, on the other.

Going beyond a specific location, online forms of education are becoming increasingly popular. These offer learning opportunities, degrees, certificates, and other types of credentials to students of all ages, including a growing number of adult learners. In his essay, Richard C. Levin describes the outpouring of online offerings, from university-led courses held remotely to start-up platforms focused on the acquisition of vocational skills.14 This mode of education has already made an enormous impact on the sector, primarily by expanding access to faculty-led courses around the world and broadening the province and scale of higher education. We cannot predict how education will be affected in the long term by large language models and other AI-supported tools, but they hold the possibility to both promote and distort current approaches to teaching and learning.

Missions for higher education can and, we believe, should illuminate a university’s greater purpose, footprint, or influence in society. While the what may drive an institution forward, it can also beg the important question of “for what?” What is the larger impact the school is trying to create in the world or in a given community? What will student learning lead to? This dimension of mission may in fact be the crux of our journalistically inspired framework. Institutions must be able to shape and clarify a raison d’être, or a strong sense of why.

One way to conceptualize an institution’s impact is by considering the influence of the university on individuals. Hardly worthy of debate, one fundamental purpose of all institutions of higher education should be the learning that takes place in the classroom. Indeed, mission statements for universities frequently include phrases such as “intellectual discovery” and “transformation.”

Documenting students’ intellectual growth throughout the university experience is one way to understand a school’s impact. Several tools can help, such as oral or written exams, public performance, and standardized tests administered and scored by external entities. Olga Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia describes an innovative way of understanding students’ learning trajectories today—during a time in which they are increasingly gathering information from online sources.15

Specifically, the PLATO (Positive Learning in the Age of InformaTiOn) research program seeks to understand how students navigate and acquire knowledge online, as well as their capacities for skills such as “Critical Online Reasoning.” PLATO stands out as a noteworthy effort to investigate what most institutions of higher education seek to accomplish (that is, student learning), or at least what many say they prioritize. And, importantly, it documents the numerous forms of mislearning across fields of study—and how they might be addressed.

An additional way to conceptualize impact is by examining the role of higher education in furthering national interests. Traditionally conceptualized as a public good, universities have been seen by some countries as instrumental in driving economic growth or global influence.16 For example, in his essay on higher education in India, Jamshed Bharucha describes how a sizeable youth population has been seen as a “source of economic hope” for the country.17 Hence, new policies in the country have sought to expand higher education to reach a greater proportion of the university-aged population in India. As another example, Frumin and Platonova describe how Soviet education was traditionally seen as a way to develop a “state good,” which meant that universities were viewed as a mechanism (or “engine”) for advancing communist ideals, aspirations, and accomplishments.18 Although the Soviet system, once supported and nurtured, no longer exists, its methods and goals can still be seen in many places.

Beyond individual students and countries, higher education can also aspire to improve society and the world. A number of schools have begun to examine their broader impact by concentrating on climate change and sustainability. For these schools, intended impact does not focus on enriching individuals, but rather on enriching the greater good.

The University of Tasmania in Australia, cited by Fernando M. Reimers in this volume, has an explicit mission of centering rigorous climate action efforts.19 One way of capturing this kind of influence is through the Times Higher Education impact rankings, a measure of how well universities address the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (or SDGs). As Reimers notes, the SDGs have been integrated into the missions of several institutions of higher education around the world, but their short- and long-term effects remain unknown.

Notably, problems can emerge when there are misalignments or disagreements within an institution around the school’s sense of why. Such misalignments seem to have played a role in the dissolving of Yale-NUS College, a short-lived but noteworthy endeavor born out of a partnership between Yale University and the National University of Singapore (NUS). At the project’s inception, Yale and NUS shared a clear impetus for the partnership: to expand liberal arts education in Singapore. Despite this mutual intention, the project proved to be rife with challenges. The Yale administration was viewed in Singapore (and perhaps elsewhere) as trying to impose a set of political values on the institution. Simultaneously, faculty members on the home campus worried about the preservation of academic freedom in a context that was vulnerable to Singapore’s nationalist trends and policies. As the partnership dissolved, NUS demonstrated a different vision for the school—one emphasizing specialization (with a few common courses) over the broad liberal arts agenda that Yale had embraced.

As Pericles Lewis, the founding president of Yale-NUS, writes in this volume, “in any institution, multiple goals are pursued by multiple constituents.”20 When these goals are too far away from one another, however, we find that institutions will be troubled. Alignment around the question of why is instrumental to institutional success—and may even be necessary for its ultimate survival.

In this essay, we have provided one possible framework for thinking deeply about missions in higher education. Specifically, we tease apart four essential elements of a mission: audience, content, place, and intended impact. If institutional leaders seek to define their university’s central purpose—and hold their institution accountable to that purpose—this framework may prove a helpful place to start.

But articulating a central mission is just one piece of the puzzle. As the value of higher education is being currently questioned, doubted, and scrutinized around the world, we believe that it is crucial for institutions not only to think deeply about mission, but also to align stakeholders around the facets of the mission. Alignment occurs when the expectations and goals of all stakeholders (in this case, students, professors, administrators) are in sync with one another and when they are mindful of the priorities of the institution and of the broader sector. Based on our own earlier studies of how professionals in various domains carry out high-quality and socially responsible work, we have found that alignment of the key parties is critical to the health of any sector of society.21 When reflecting on the alignment within an institution, university leaders might ask themselves: What are the goals of this university? What are our students’ goals? Does the faculty body share these goals? If not, what can we do to address these discrepancies?

Writing in early 2024, we realize that alignment has become an especially critical goal for the United States. Indeed, situated at Harvard University, we can confirm that disagreements surrounding the central mission of higher education are all too evident. In the midst of a series of high-profile presidential resignations at universities nationwide and fierce attacks on universities from many political corners, the purpose of higher education—or the why for the sector—has become a contentious issue. At the extremes, some constituents posit that the university should focus primarily on the goals of diversity, equity, and inclusion, while others argue with equal fervor that institutions should prioritize free speech, argument, and debate above all else.

Though the goal of creating strong alignment around the mission of higher education may be a lofty one, we believe that the pursuit of common ground is essential—not only for the flourishing of individual institutions of higher education, but for the thriving (and indeed, survival) of the sector at large.

As the essays in this volume suggest, missions for higher education are wide-ranging. Many institutions focus sharply on serving a particular audience, while others focus on specific skills and areas of knowledge that students should acquire. Some institutions craft a mission that centers on their schools’ respective geographic locations, while others are preoccupied primarily with their university’s larger footprint in the world.

Our discussion of the fourth dimension addresses the impact and influence of mission—the why of higher education. Both Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia and Reimers focus on the effect of specific academic programs on students—in one case, how students process new information (and misinformation), and in the other, how students come to care about climate change.22 But as social scientists, we know that demonstrating the overall impact of the higher-education experience is extremely challenging. At the same time, it is important to find ways to demonstrate its “value add”—the ways in which it can and should make a difference for individuals and society.

In the United States, there have recently been efforts to assess the impact of the standard four-year education in the liberal arts. As an important example, the Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA) was launched in 2000. In this standardized test, students are not probed for content knowledge, but rather for skills involving critical thinking and problem-solving. Analyses of the CLA point to disappointing results from students—sociologists Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa found that 45 percent of students indicate little to no significant change over the first half of the undergraduate experience.23 Other efforts to measure impact have been more encouraging. In 2021, social psychologist Richard Detweiler published an empirical study affirming positive outcomes of higher education across one thousand individuals.24 However, while he collected promising and rigorous data, the study was based on retrospective accounts of the undergraduate experience from ten, twenty, and forty years earlier. We do not know whether these graduates are truly different—and if they are, why. Nor do we know whether similar effects could be documented today.

In our own national study of higher education in the United States, we put forth a new measure called Higher Education Capital (HEDCAP).25

This instrument aims to focus assessment of intellectual capacities over the course of the undergraduate experience. Accordingly, HEDCAP denotes the ability to attend, analyze, reflect, connect, and communicate on issues of importance and interest.

Specifically, we blind-scored one thousand student interviews about higher education, looking for evidence as students discussed the university experience. Among the varied responses, we considered as evidence any questions that clarified or lent insight to our understanding of students’ experiences; connections between different questions throughout the interview; clear articulation of a point of view with coherent examples; and/or description that included comparison and contrast of their own perspectives to others’. In brief, we assessed their ability to engage in and carry on a conversation about something they knew well! We used a simple scoring method, ranging from little to no HEDCAP to a lot of HEDCAP. Importantly, we found that while most students across ten schools show evidence of “some” HEDCAP, in comparing first-year students to graduating students, across all schools, the data show “growth” over the duration of their university education. But more important, HEDCAP improved much more on certain campuses than on others. Determining the reason(s) for this pattern would be crucial to replicate this result elsewhere.

HEDCAP is our own attempt at demonstrating that higher education can—and should—make a difference in the subsequent lives of its graduates. Some of the national and international ranking systems also attempt to do the same, by comparing the academic “quality” of institutions. But as Gökhan Depo points out, rankings are not only flawed—they do not capture what we think should be one of higher education’s primary goals.26 One might even assert that rankings contribute to mission sprawl! Indeed, while the Times Higher Education World University Rankings are widely regarded around the world, their criteria prioritize research productivity, citations per professor, and industry income—rather than student learning, which HEDCAP and the CLA at least seek to address. According to the criteria featured in the rankings, one might assume that the sector promotes individual prestige, productivity, and profit, rather than intellectual capacities and growth.

To prove its worth beyond jobs and employment for individual gain, we need to be clear about the original educational aims of higher education and hold institutions and stakeholders accountable to delivering on what the mission promises. And to use the example of our own home institution, if seeking “truth” represents the key purpose of an institution of higher learning, every stakeholder—including faculty and administrators on campus—should be able to easily articulate that mission and ultimately embody it.

To be sure, change and innovation are necessary for any sector. If a sector is to educate a diversity of students from around the world so that they can address new health, environmental, and political challenges, constant adjustments need to be made. As several essays in this volume testify, new institutions have been developed to educate those individuals who have been underserved and did not have access to a quality education, new teaching pedagogies and academic programs have been created to engage students in “real world” problems, and even the physical boundaries of buildings and classrooms have been stretched to new places—online and across the globe. However, especially at this time of change, we need institutions to double down on the central animating idea of mission and make their own mission clear and verifiable. And, to put our cards directly on the table: we hope to preserve what has, at its best, been special and distinct about higher education—providing for all students a rich intellectual experience, one that should last a lifetime and contribute to a larger collective good.

authors’ note

We are grateful to the Kern Family Foundation for supporting our research on higher education and to Christopher Stawski for his helpful wisdom and support.