Two Theories

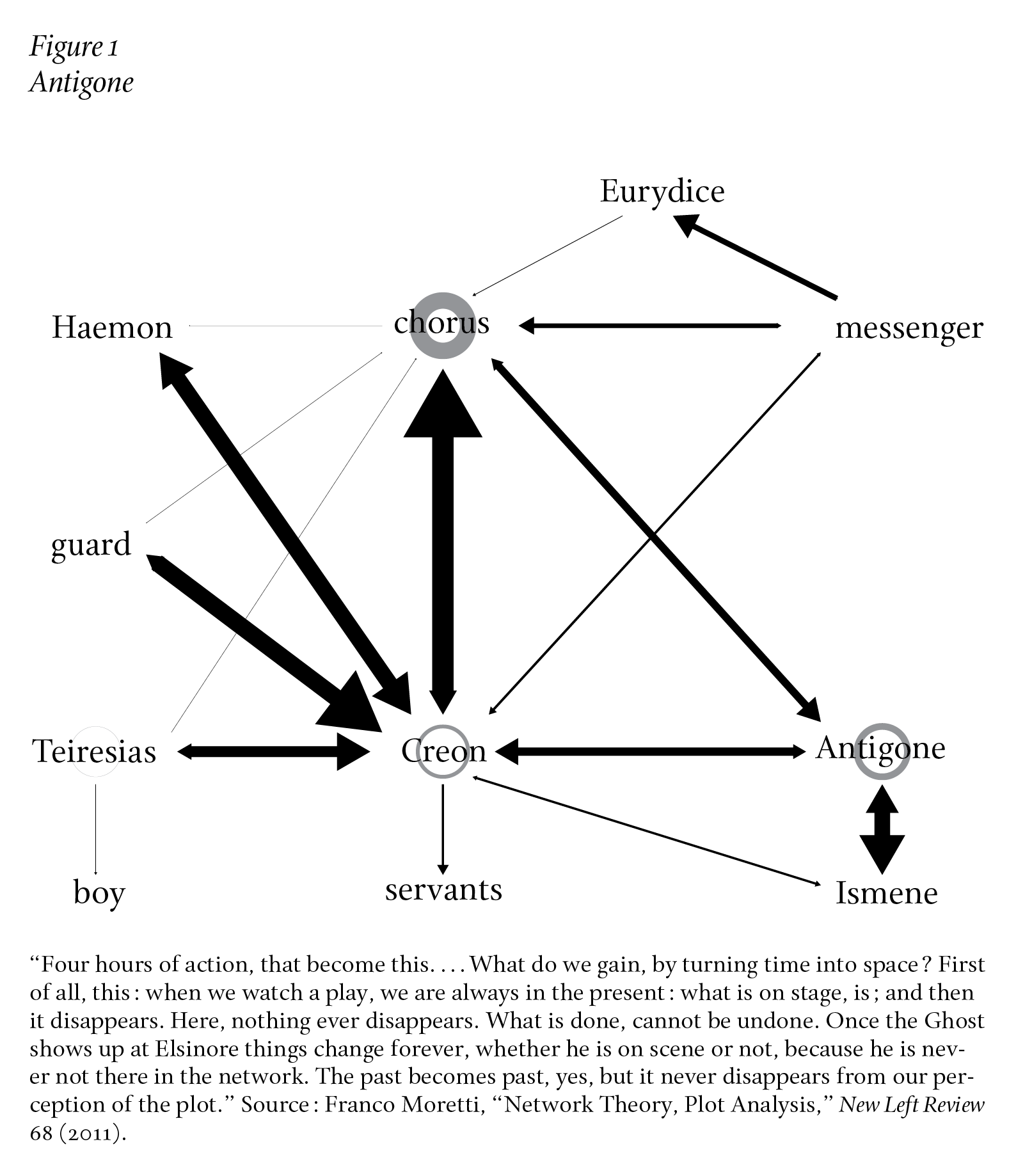

Let me begin with two images: the character-networks of Antigone and Les Misérables. Both plots have been turned into networks on the basis of the interactions among characters, and yet the outcome couldn’t be more unlike.1 While Sophocles’s system is small, tight, and visibly centered around the fatal figure of Creon, strategos of Thebes, Hugo’s crowded network shows dozens of figures with a single link to the body of the text, evoking the “minor-minor” characters of Alex Woloch’s The One vs. the Many.2 One can still study minor characters in tragedy, of course—“Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are dead”—or the centripetal pull of certain scenes in Fielding, or Dostoevsky, or even Ulysses. But, at bottom, tragedies and novels pose different questions to critical reflection, encouraging it to move in opposite directions. And that is indeed what the theory of tragedy and the theory of the novel have done.

Beginning with Plato and Aristotle—and then Hume, Voltaire, Schelling,Hegel, Kierkegaard, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche . . . Scheler, Unamuno, Heidegger, Camus . . . Foucault, Derrida, Lacoue-Labarthe, Žižek, Butler, Menke—philosophers have dominated the theory of tragedy. At times, they have done so by addressing strictly aesthetic issues, like the structure of tragic plot in the Poetics, the one-sidedness of dramatic characters in Hegel’s Aesthetics, or the function of the chorus in The Birth of Tragedy; more often, they have taken tragedy to be the ideal terrain for general issues like the threat of emotions to political stability (The Republic), the clash between liberty and the course of the world (Schelling’s Philosophical Letters on Dogmatism and Criticism), the struggle between the imperatives of the State and the bonds of the family (Hegel’s Phenomenology), the internal contradictions of the will (Schopenhauer’s World as Will and Representation), the distinction between ancient pain and modern sorrow (Kierkegaard’s Either/Or), all the way to Nietzsche’s critique of the homo theoreticus, Lukács’s aptly titled “Metaphysics of Tragedy,” and Heidegger’s “attempt . . . to assess who the human being is” via his reading of Antigone’s second choral ode in the Introduction to Metaphysics.

Under the weight of these questions, the analysis of a specific literary form that was the object of the Poetics was replaced by a philosophy of “the tragic” as a self-standing entity: an “essentialization” or, better, a “derealization of tragedy,” as William Marx has called it,3 which was further exacerbated by the frequent focus on just a handful of notions—“catharsis,” “collision,” “reconciliation,” the chorus—as the key to the whole enterprise.4 The “generic understandings of tragedy” in Schiller, Schelling, Schlegel, Hegel, and Hölderlin, Joshua Billings has written, are “substantially based on a single play” (typically, Oedipus Tyrannus or Antigone);5 in the past two hundred years, we have managed to add a couple more. Within literary studies, the theory of tragedy is clearly the model for the study of a single form with an exclusive canon, and very sharp boundaries.

Socrates was said to be a friend of Euripides; Plato, to have composed tragedies himself. True or not (almost certainly not), these views express the fact that the study of tragedy arose simultaneously with tragedy itself. For its part, the theory of the novel took shape approximately two millennia after the composition of the earliest novels. Almost certainly due to the feeling that the novel was an illegitimate form, with no place within the spectrum of classical genres, this colossal hiatus between texts and theory was filled by all sorts of short-term commentaries, generally dismissive or downright censorious. Philosophical interest shrank to a few great intuitions of German romanticism, the most memorable of which—Schlegel’s fragment 116, from the Atheneum of 1798—pursued the exact opposite of an essentialization of novelistic form:

Romantic poetry is a progressive, universal poetry. Its aim is not merely to reunite all the separate species of poetry and put poetry in touch with philosophy and rhetoric. It tries to and should mix and fuse poetry and prose, inspiration and criticism, the poetry of art and the poetry of nature; and make poetry lively and sociable, and life and society poetical; poeticize wit and saturate the forms of art with every kind of good, solid matter for instruction, and animate them with the pulsations of humor.6

Philosophy, rhetoric, poetry, prose, criticism, nature, life, society, wit, instruction, humor . . . Too much! In practice, this universal-progressive utopia was disarticulated among a plurality of critic-historians—Shklovsky, Lukács, Bakhtin, Auerbach, Watt, Barthes, Jameson—with the occasional incursions of anthropologists (Claude Lévi-Strauss, René Girard), social scientists (Benedict Anderson), historians (Mona Ozouf), or psychoanalysts (Marthe Robert).7 Moreover, those two millennia during which novels were being written, but not written about, created a literary landscape where—in lieu of the handful of works written in a single language over a couple of generations addressed in the Poetics—theorists had to confront thousands of texts of all sizes and structures, in prose and in verse, from disparate epochs, languages, and places. Having to account for Chrétien and Cervantes, Sterne and Melville and Kafka—and eventually also for Genji and The Story of the Stone, Noli me tangere, Macunaíma, and The Interpreters—forced literary analysis into uncharted territory: if the study of tragedy had always been openly and un-self-consciously Athenocentric, the theory of the novel had to come to terms—however slowly and reluctantly—with the mare magnum of Weltliteratur.8 For all practical purposes, the two theories inhabited different worlds.

As is often the case, geography had morphological consequences as well, and the theory of the novel quickly discovered that it needed to find room—conceptual room—for the kaleidoscope of novelistic subgenres. Their proliferation is not only a feature of modern literary systems (as in the forty-four British subgenres that I once reconstructed):9 the decades around 1200 had already been singled out by Cesare Segre for their “extraordinary eidogenetic activity”—“a thorough inventory of representable reality, from the roman d’aventure to the roman courtisan, from the roman intimiste to the roman burlesque or comique, from the roman exotique to the roman picaresque”10—while Andrew Plaks had traced the same pattern in premodern China,11 and Tomas Hägg, even earlier in time, had recognized it as the original matrix of the ancient Greek novel.12 Theoretical reflection inclined toward historical phenomenology: still sternly logical in Lukács’s tripartite Theory, more open in Bakhtin’s interplay of local forms and main novelistic “lineages,” and completely explicit in the gusto for morphological ramifications of recent attempts like Pavel’s and Mazzoni’s.13 In fact, the most distinctive form taken by the theory of the novel may well be the unplanned collective cartography of specific subgenres: from Lukács’s Historical Novel, Rico’s Novela picaresca, Bollème’s Bibliothèque bleue, and Vinaver’s Rise of Romance to, more recently, Catherine Gallagher on the industrial novel, Katie Trumpener on the “national tale,” and Stefano Ercolino’s dyptich on the maximalist and essayistic novel.14

“A group containing many diversified species,” wrote the British ecologist G. E. Hutchinson in an essay that has become legendary, “will be able to seize new evolutionary opportunities more easily than an undiversified group.”15 They are the right words to understand the planetary success of the novel: as new social groups gained access to literacy, the novel’s formal diversification allowed it to swiftly occupy—“the novel permeates with its colour all of modern literature” observed Schlegel in the Athenaeum—the cultural niches that were opening up. Here, too, the difference with tragedy is unmistakable. The latter had long dominated the literary field, of course, but without ever changing the field itself: majestically towering above all other forms, it had left them free to pursue their less exalted aims. Not so the novel, which, by relentlessly “parod[ying] other genres,” interfered directly with their development until, as Schlegel had prophesized, the entire literary space became indeed pervasively “novelized.”16

A philosophy of the tragic; a phenomenology of novelistic subgenres. Not surprisingly, the interaction between history and form differs markedly in the two traditions. “Aeschylus increased the number of actors from one to two,” wrote Aristotle, “reduced the choral component, and made speech play the leading role. Three actors and scene painting came with Sophocles.”17 And this was it: “tragedy ceased to evolve, since it had achieved its own nature.” Tragedy continued to evolve, to be sure, but not that much, really, in the two-and-a-half millennia that have elapsed since the Poetics. Between the direct reincarnations of great ancient figures—mostly women: Medea, Elektra, Iphigenia, Helen, Hekuba, Phaedra, Antigone—and more subterranean metamorphoses (Oedipus turning into Hamlet, Sigismundo, Don Carlos, Gregers Werle), the theory of tragedy has had to measure itself against this stubborn vitality of the tragic past: a spectral longue durée in which the initial form has been exceptionally successful at resisting historical change. Though never quite a narrative of decline—after all, how could it: Shakespeare, Calderon, Racine, Büchner, Ibsen—the study of tragedy has thus been characterized by an increasingly fatalistic mood, well encapsulated—The Death of Tragedy—by its major postwar bestseller.

The Death of Tragedy, The Rise of the Novel. No gloom at all in the other camp, and not much respect for the past, either. Theory of the novel, theory of the new. “We have invented the productivity of the spirit,” declares one of Lukács’s most eloquent pages,18 and one couldn’t choose a better motto for an aesthetics of modernity. “Other kinds of poetry are finished,” had observed Schlegel in the Athenaeum, but “the romantic kind of poetry should forever be becoming”; “only that which is itself developing can comprehend development,” echoed Bakhtin in “Epic and Novel.”19 Here, historical change—Bakhtin’s “present in all its openendedness”—is no longer an obstacle to morphological achievement, but the very basis of its unprecedented plasticity.

Why tragedy? Answers have converged around its ethico-political significance,20 from Aristotle’s Delphic dictum—“through pity and fear accomplishing catharsis”21—to Christian warnings on the hazards of worldly greatness, early modern awe at the implacable energy of ambition and the antinomies of freedom in German idealism. “Speaking in general,” Leo Strauss has observed, “pre-modern thought placed the accent on duties, and rights, when they were considered at all, were viewed only as a consequence of duties.”22 An emphasis on duties: “the jurisdiction of the stage begins where the domain of secular laws ends,” declared Schiller in his 1784 speech on the influence of the theater: “only here do the great of the world hear what they never or seldom hear—Truth—and see what they never or rarely see: Man (den Menschen).”23

This ethico-political dominant has made it notoriously difficult to spell out what kind of pleasure is associated with tragic form. Schiller’s “Of the Cause of Pleasure We Derive from Tragic Objects” has much to say about reason, ethics, and even pain—“the highest moral pleasure is always accompanied by pain”24—and very little about enjoyment. Even The Birth of Tragedy, which provided the most celebrated attempt in the opposite direction, sounds often like a petitio principii about the “health” of pre-Socratic Greece—“what then would be the origin of tragedy? Perhaps joy, strength, overflowing health, excessive abundance?”25—rather than a genuine account of the sources of tragic pleasure; while the famous paragraph on the world being “justified only as an aesthetic phenomenon,” rests for its part on a Wagnerian mood that would have been inconceivable in the ages before Tristan.26

Why the novel? “Caramelos y novelas andan juntos en el mundo,” wrote Domingo Sarmiento around the middle of the nineteenth century: “candy and novels go hand-in-hand in the world, and the culture of a nation can be measured by how much sugar they consume and how many novels they read.”27 Sugar had been a protagonist of the eighteenth-century “consumer revolution,” and Sarmiento’s sarcasm highlights the novel’s status as the archetypal literary commodity—one that promises easy and immediate gratification. “Unlike other genres,” observed Lukács, the novel “has a caricatural twin almost indistinguishable from itself . . .: the entertainment novel.”28 Where the problem, it seems, is less the existence of Jack Sheppard or The Wide Wide World than the fact that all novels incorporate at least some of the vulgarity of Unterhaltungslektüre (entertainment novel). Too much sugar, in the novel’s recipe, whence the Sisyphean attempt to “nobilitate” it (Fielding, Flaubert, James, Proust) by severing all links with plebeian taste.

Too much pain, too much candy. Each in its own way, tragedy and the novel seem to drift away from the “right” amount of aesthetic pleasure, forcing their respective theories to struggle with this lack of measure. A problem? I don’t think so. As two extreme cases, tragedy and the novel help us delimit opposite dimensions of the aesthetic realm, suggesting that its pleasure should not be seen as a fixed category, but as a spectrum of divergent outcomes. It is one thing to concentrate on a play about the fate of the polis knowing that we may be involved in it, and quite another to lose ourselves in an improbable adventure that we’ll never experience; but there is pleasure in both, and we should try to recognize the centers of gravity around which it has clustered over time. A historical anthropology of literary pleasure(s) will not by itself unify the two theoretical traditions, but will at least place them within a single conceptual landscape. That would be a new starting point.