Paying for Expanded Care Provision

Children receiving better care grow up earning more, paying more in taxes, committing fewer crimes, and needing less help from government. That these and many other benefits of investment in care cannot be captured by private parties is what underlies the powerful case for public investment. Yet many voters resist such investment in the belief that the necessary taxes would require painful sacrifices. This belief, however, rests on a simple cognitive illusion. Since the wealthy already have what anyone might reasonably need, their ostensible concern is whether higher taxes would make it more difficult to buy life’s special extras. But because such things are inherently in short supply, the ability to purchase them depends almost exclusively on relative bidding power, which is completely unaffected by top tax rates.

In a landmark 2014 study, economists Raj Chetty, John Friedman, and Jonah Rockoff found that elementary school students who had been assigned to better teachers (as measured by their effect on standardized test scores) are less likely to bear children as teenagers and more likely to attend college.1 Chetty, Friedman, and Rockoff also estimated that replacing a poor teacher with an average one would boost the present value of students’ lifetime income by approximately $250,000 per classroom. Students taught by better teachers not only earn more and pay more in taxes, but they also commit fewer crimes and need less help from government-supported programs.

These findings suggest that investments in higher quality teaching would yield enormous dividends. But as with other investments in care provision discussed in this volume, a large proportion of the relevant returns is public. Because individuals in a position to make the necessary investments cannot capture these returns, private incentives are insufficient to secure these resources. That, in a nutshell, is the case for public investment in care.

In a well-functioning democracy, voters would empower legislators to invest in additional care whenever the returns from doing so exceed the cost. But as other essays in this volume suggest, that does not appear to be happening in the United States.

Many government officials seem to recognize that the nation would benefit from substantially greater investment in care provision. The proximate cause of the shortfall is taxpayer resistance. Voters might acknowledge that greater investment in care would yield high returns, but they also appear to believe that those returns would not compensate for the consumption reductions required by higher taxes.

In this essay, I will describe simple, unintrusive changes in tax policy that would more than suffice to finance major increases in care provision, and also to eliminate shortfalls in other important categories of public investment. The central claim I will defend is that taxpayer resistance to these changes stems from a garden-variety cognitive illusion that paying higher taxes would make it more difficult to buy life’s special extras.

Economic orthodoxy’s claim that market incentives promote efficient outcomes rests on the deeply implausible assumption that the satisfaction provided by any good is a function of only its absolute attributes. That is clearly not true of an interview suit. If you are one of several similarly qualified applicants aspiring to land the same investment banking job, it is strongly in your interest to look good when you show up for your interview. But looking good is a relative concept. It means looking better than rival candidates. All else equal, if they show up in three-hundred-dollar suits off the rack, you will be more likely to make a favorable first impression, and more likely to get a callback, if you show up in a bespoke suit costing several thousand dollars.

Recruiters may not be able to recall even the color of the suit you wore, but they will have sensed whether you looked the part. Spending more is thus rational from the individual job seeker’s perspective, but irrational from the perspective of job seekers as a group. They may understand that it would be better if all had spent less. But if others were spending more, no one would have reason to regret spending more as well.

Evaluation is often heavily context-dependent, which has profound implications for welfare economics. The behavioral scientists who study the determinants of human flourishing have produced a large and contentious literature that speaks to this claim.2 One of the least controversial and most consistent findings in this literature is that, beyond a point long since passed in the industrial nations, across-the-board increases in many forms of private consumption yield no measurable gains in either health or life satisfaction. When all mansions double in size, those living in them become neither happier nor healthier than before. Nor are marrying couples any happier today than in 1980, even though constant-dollar outlays for their wedding receptions are now more than three times what they were then.

Most income gains since 1980 have accrued to people in the top fifth of the earnings distribution, and within even that group, the lion’s share went to the highest earners. Spending levels for these people were already well past the point at which further increases served merely to shift the frames of reference that shape what is deemed adequate.

An imposing body of careful scientific research thus provides no reason to believe that Americans were meaningfully better off in, say, 2019 (the last year before the COVID-19 pandemic began) than in 2012, even though the inflation-adjusted total value of the nation’s goods and services was more than $3 trillion higher in 2019.

The waste we incur on a grand scale would be of little interest if there were nothing practical that could be done about it. Yet just a few simple, unintrusive policy changes could improve matters greatly. For instance, we could scrap the progressive income tax in favor of a far more steeply progressive tax on each family’s annual consumption expenditure. People would report their incomes to the tax authorities as they do now, and then document how their stock of savings had changed during the year, as many already do for tax-sheltered retirement savings accounts. Taxable consumption would then be calculated as income minus savings minus a generous standard deduction. Tax rates would start low, then escalate as taxable consumption rose.

Taxing only spending would require that rates on the highest levels of taxable consumption be higher than the highest current tax rates on income. They could indeed be much higher since rates under the current income tax are constrained by the effort to not inhibit savings and investment. (Under a progressive consumption tax, higher top rates actually encourage savings and investment.)

This simple policy change would also encourage people to choose smaller houses, spend less on automobiles and interview suits, and reduce outlays on wedding receptions, coming-of-age parties, and the like. Because those changes would merely shift the relevant frames of reference that define what we consider to be adequate, they would be essentially painless. In contrast, revenue from the tax could fund increased investments in care, medical research, infrastructure refurbishment, climate change mitigation, and a host of other things that actually matter.

If higher taxes would pay for public investments whose utility would more than compensate for the corresponding reductions in private consumption, why don’t voters generally, and prosperous voters in particular, support politicians who favor those investments?

My answer is that voter resistance stems from a simple cognitive illusion: voters believe that having to pay higher taxes would make it more difficult to buy what they want. Like many illusory beliefs, this one may seem self-evident; yet for prosperous voters, it is completely baseless.

When someone asks, “How will an event affect me?” the natural first step is to try to recall the effects of similar events in the past. When high-income people try to imagine the impact of higher taxes, Plan A is thus to summon memories of how they felt in the wake of past tax increases. But that strategy does not work in the current era because most high-income people alive today have experienced steadily declining tax rates. In World War II, the top marginal tax rate in the United States was 92 percent. By 1966, it had fallen to 70 percent. In 1982, it was 50 percent, and it is now just 37 percent. Apart from brief and isolated increases almost too small to notice, top marginal tax rates have fallen steadily since their World War II peak. Similar declines have occurred in other countries.

When Plan A fails, we go to Plan B. Because paying higher taxes means having less money to spend on other things, a plausible alternative cognitive strategy is to estimate the effect of tax hikes by recalling earlier events that resulted in lower disposable income—an occasional business reverse, for example, or a losing lawsuit, divorce, or housefire, maybe even a health crisis. Rare is the life history that is completely devoid of events like these, which share a common attribute: they make people feel miserable.

More important, such events share a second feature, one that is absent from an increase in taxes: they reduce our own incomes while leaving others’ incomes unaffected. Higher taxes, in contrast, reduce all incomes in tandem. This difference holds the key to understanding what I have elsewhere called “the mother of all cognitive illusions.”3

As most prosperous people would themselves be quick to concede, they have everything anybody might reasonably need. If higher taxes pose any threat, it would be to make it more difficult for them to buy life’s special extras. But like an effective interview suit, a special extra is a relative concept. To be special means to stand out in some way from what is expected. And almost without exception, special things are in limited supply. There are only so many penthouse apartments with sweeping views of Central Park, for instance. To get one, a wealthy person must outbid peers who also want it. The outcomes of such bidding contests depend almost exclusively on relative purchasing power. And since relative purchasing power is completely unaffected when the wealthy all pay higher taxes, the same penthouses end up in the same hands as before.

Prosperous Americans might reasonably object that higher tax rates would put them at a disadvantage relative to oligarchs from other countries in the bidding wars for trophy properties in the United States. But that disadvantage could be eliminated easily by the imposition of a stiff purchase levy on nonresident buyers.

The mother of all cognitive illusions implies that societies can enjoy the fruits of additional public investment without having to demand painful sacrifices from anyone. If that strikes you as a radical claim, that is because it is. Yet the claim follows logically from only one simple premise: that beyond some point (again, one that has long since been passed in the West), across-the-board increases in most forms of private consumption do little more than raise the bar that defines what people consider adequate. No one in the scientific community seriously questions this premise.

The bias toward private over public spending bears a striking resemblance to the modern left’s description of market failure, which was shaped in large measure by the writings of economist John Kenneth Galbraith. As he put it in his 1958 book The Affluent Society, “The family which takes its mauve and cerise, air-conditioned, power-steered, and power-braked automobile out for a tour passes through cities that are badly paved, made hideous by litter, blighted buildings, billboards, and posts for wires that should long since have been put underground.”4 The automobile features he described are no longer considered luxuries. If he were alive today, however, he would still insist that people would be happier if society spent more on public goods and less on private goods. But he and I propose strikingly different accounts of the causes of this imbalance.

For example, in his 1967 book The New Industrial State, Galbraith attacked free-market enthusiasts’ insistence that consumer demands stem from informed decisions based on self-interested preferences, which firms try to satisfy in the least costly ways.5 In place of that narrative, he offered his “revised sequence,” which echoed Karl Marx’s disdain for powerful corporate interests: firms offer what is cheapest and easiest for them to produce, then use Madison Avenue wizardry to bamboozle consumers into buying it.

In contrast, the account of market failure I have sketched in this essay accepts economic orthodoxy’s assumptions that consumers are rational and that markets are workably competitive. Its point of departure is the observation that choices we find attractive as individuals often lead to outcomes we dislike. As in the familiar stadium metaphor, all stand to get a better view, only to discover that no one sees any better than if all had remained comfortably seated. As I put it in the title of a forthcoming book, standing to see better is Smart for One, Dumb for All. The emphasis on private consumption over public investment results from a similar conflict between individual and collective interests.

Galbraith’s account of spending imbalance has drawn heavy criticism from free-marketeers, who have long voiced skepticism about his claim that consumers are easily bamboozled. They remind us that although the Ford Motor Company launched its new Edsel with one of the biggest ad campaigns in history, the car failed miserably and was discontinued within two years. To those who insisted that advertising can persuade people to buy useless products, critics responded plausibly that Madison Avenue should be even more effective at promoting goods that deliver real value.

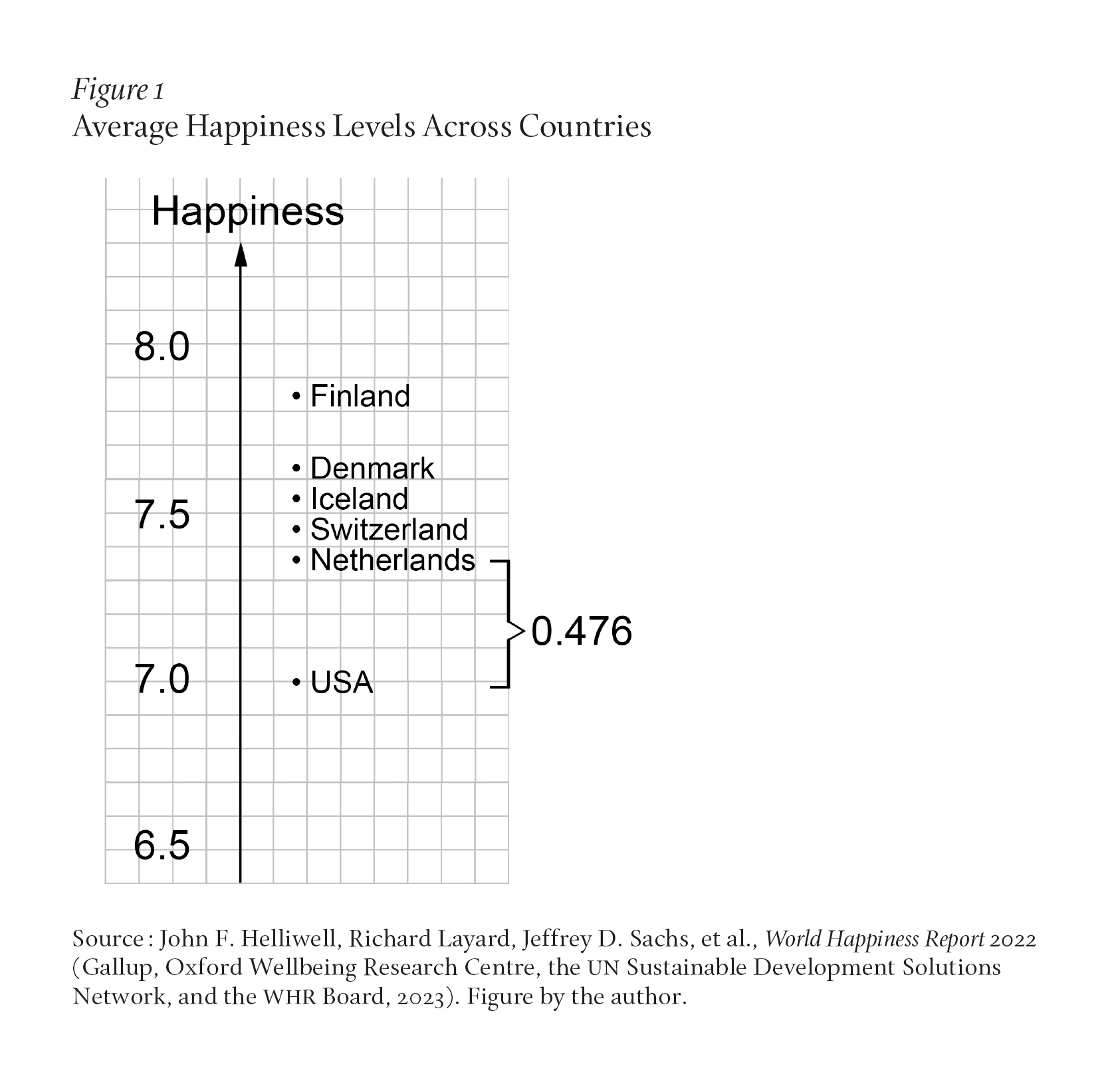

Although Galbraith and I offer different reasons for wasteful spending patterns, we both claim that people fare better in societies where there are higher rates of public investment. Available evidence supports this claim. Much of this evidence comes from the World Happiness Report (Figure 1), in which people in countries around the globe are periodically asked the following question: on a ten-point scale, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days (where zero means “not at all satisfied” and ten means “completely satisfied”)?6

By this simple metric, Finland, Denmark, Iceland, Switzerland, and the Netherlands are consistently among the five happiest among countries worldwide. Those five and the next ten countries in the world happiness rankings tax top earners more heavily and spend significantly more on public goods than the United States (ranked sixteenth) does.

Although being happy is of course not the only goal in life, there is ample reason to view higher happiness scores as a good thing. As the World Happiness Report points out, higher scores are closely linked to country characteristics known to promote human flourishing. These include, among others, income per capita, “social support, healthy life expectancy, freedom, generosity, and [absence of] corruption.”7 It is thus a reasonable conjecture that most people would consider it a positive outcome if a policy change made them happier without compromising other goals they care about.

Critics have long objected that higher top marginal tax rates would reduce incentives to work hard and take risks. But those concerns find little support in cross-national studies, some of which use a country’s number of billionaires per capita as a measure of the strength of its entrepreneurial incentives. For instance, although the top marginal tax rate in Sweden is 52.3 percent, more than 15 percentage points higher than in the United States, the country has more than 50 percent more billionaires per capita than the United States.

If spending patterns that seem smart for one are in fact often dumb for all in the ways I have described, then simple, unintrusive tax policy changes could eliminate sufficient waste to cover not only the shortfalls in care investment identified by other authors in this volume but also those in many other pressing public investment categories.

author’s note

Portions of this essay are adapted from my forthcoming book Smart for One, Dumb for All: Reflections of a Radical Pragmatist.